|

Note: Large images and

tables on this page may necessitate printing in landscape mode.

Copyright

©2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved.

Emergency

Medicine Atlas > Part 1. Regional

Anatomy > Chapter 1. Head and Facial Trauma >

|

Basilar Skull Fracture

Associated Clinical Features

The skull base comprises the

floors of the anterior, middle, and posterior cranial fossae. Trauma resulting

in fractures to this basilar area typically does not have localizing

symptoms. Plain skull radiographs are poor in identifying these

fractures. Indirect signs of the injury may include visible evidence of

bleeding from the fracture into surrounding soft tissue, such as a

Battle's sign (Figs. 1.1, 1.2) or "raccoon eyes" (Fig. 1.3).

Bleeding into other structures—including hemotympanum (Fig. 1.4) or

blood in the sphenoid sinus seen as an air-fluid level—may also be

seen. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks may also be evident and noted as

clear or pink rhinorrhea. If CSF is present, a dextrose stick test may be

positive. The fluid can be placed on filter paper and a "halo"

or double ring may be seen (Fig. 1.5).

|

|

|

|

|

Battle's

Sign Ecchymosis in the

postauricular area develops when the fracture line communicates with

the mastoid air cells, resulting in blood accumulating in the

cutaneous tissue. This patient had sustained injuries several days

prior to presentation. (Courtesy of Frank Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Battle's

Sign A subtle Battle's sign is

seen in this patient with head trauma. This sign may take hours to

develop fully. (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Raccoon

Eyes Ecchymosis in the

periorbital area, resulting from bleeding from a fracture site in the

anterior portion of the skull base. May also be caused by facial

fractures. (Courtesy of Frank Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

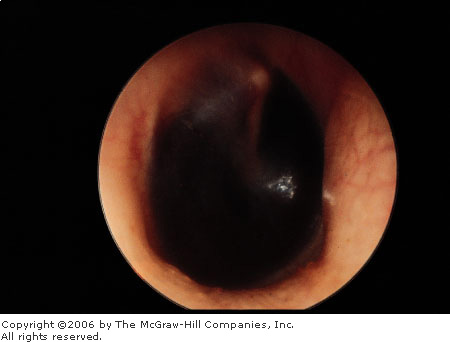

Hemotympanum Seen in a basilar skull fracture when the

fracture line communicates with the auditory canal, resulting in

bleeding into the middle ear. Blood can be seen behind the tympanic

membrane. (Courtesy of Richard A. Chole, MD, PhD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cerebrospinal

Fluid Leak This example, from

the nose, can be difficult to distinguish from blood or mucus. The

distinctive double-ring sign, seen here, comprises blood (inner

ring) and CSF (outer ring). The reliability of this test

has been questioned. (Courtesy of David W. Munter, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Direct trauma without skull

fracture can result in external ecchymosis. Barotrauma can cause

hemotympanum. Facial injuries and fractures can cause facial ecchymosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The mainstay of therapy is to

identify underlying brain injury, which is best accomplished by computed

tomography (CT). CT is also the best diagnostic tool for identifying the

fracture site, but fractures may not always be evident. Evidence of open

communication, such as a CSF leak, mandates neurosurgical consultation

and admission. Otherwise, the decision for admission is based on the

patient's clinical condition, other associated injuries, and evidence of

underlying brain injury as seen on CT. The use of antibiotics in the

presence of a CSF leak is controversial because of the possibility of

selecting resistant organisms.

Clinical Pearls

1. The clinical manifestations

of basilar skull fracture may take several hours to fully develop.

2. Since plain films are

unhelpful, there should be a low threshold for head CT in any patient

with head trauma, loss of consciousness, obtundation, severe headache,

visual changes, or nausea or vomiting.

3. The use of filter paper or a

dextrose stick test to determine if CSF is present in rhinorrhea is not

100% reliable.

|

|

Depressed Skull Fracture

Associated Clinical Features

Depressed skull fractures

typically occur when a large force is applied over a small area. They are

classified as open if the skin above them is lacerated (Fig. 1.6) and

closed if the overlying skin is intact. Abrasions, contusions, and

hematomas may also be present over the fracture site. The patient's

mental status can range from comatose to fully alert depending on the

extent of the associated brain injury. Soft tissue bleeding and swelling

may be present. Evidence of other injuries such as a basilar fracture or

facial fractures may also be present.

|

|

|

|

|

Depressed

Skull Fracture A scalp

laceration overlying a depressed skull fracture. Wearing a sterile

glove, the examiner should digitally explore all scalp lacerations

for evidence of fracture or depression. (Courtesy of David W. Munter,

MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Direct trauma can cause

abrasions, contusions, hematomas, and lacerations without an underlying

depressed skull fracture. Every laceration to the scalp should be

explored and palpated to rule out depression of a fracture. Alterations

in mental status may occur with or without fracture. Penetrating injuries

to the skull and brain can produce a similar clinical picture.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Plain films have been suggested

for suspected depressed skull fractures and if positive should be

followed by CT, which will more accurately demonstrate the degree of

depression as well as any underlying brain injury (Fig. 1.7). Others

suggest that plain films offer little diagnostic utility and recommend CT

with its more accurate bone windows for any suspected depressed skull

fracture. When depressed skull fractures are noted on plain films or CT,

immediate neurosurgical consultation is required. Open fractures also

require antibiotics and tetanus prophylaxis as indicated. The decision to

observe or operate immediately is made by the neurosurgeon. Children

below 2 years of age with skull fractures can develop leptomeningeal

cysts. These cysts, which are extrusion of CSF or brain through dural

defects, are associated with skull fractures. For this reason, children

below age 2 with skull fractures require follow-up or admission.

|

|

|

|

|

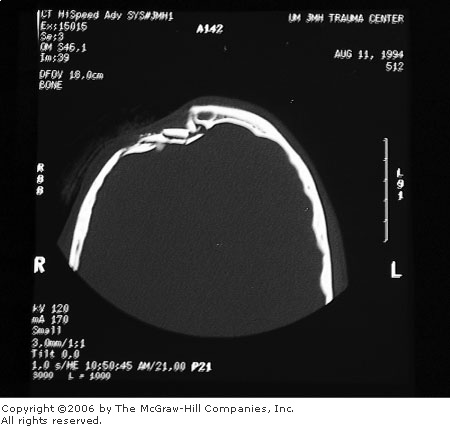

Depressed

Skull Fracture CT

demonstrating depressed skull fracture. (Courtesy of David W. Munter,

MD.)

|

|

Clinical Pearls

1. Gently palpate all scalp

injuries including lacerations for evidence of fractures or depression.

When fragments are depressed more than 3 to 5 mm below the inner table,

penetration of the dura and injury to the cortex are more likely.

2. Children with depressed

skull fractures are more likely to develop epilepsy.

3. The index of suspicion for

nonaccidental trauma should be raised for children below 2 years of age

with depressed skull fractures.

|

|

Nasal Injuries

Associated Clinical Features

Clinically significant nasal

fractures are almost always evident on examination, with deformity,

swelling, and ecchymosis present (Fig. 1.8). Injuries may occur to other

surrounding bony structures, including fractures of the orbit, frontal

sinus, or cribriform plate. A history of a mechanism with significant force,

loss of consciousness, or findings of facial bone injury or CSF leak

should alert the clinician to look for these associated injuries.

Epistaxis may be due to a septal or turbinate laceration but can also be

seen with fractures of surrounding bones, including the cribriform plate.

Septal hematoma (Fig. 1.9) is a rare but important complication that, if

untreated, may result in necrosis of the septal cartilage and a resultant

"saddle-nose" deformity.

|

|

|

|

|

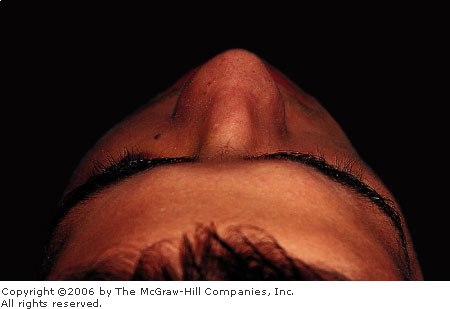

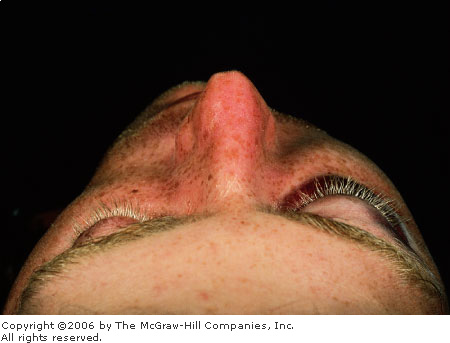

Nasal

Fracture Deformity is evident

on examination. Note periocular ecchymosis indicating the possibility

of other facial fractures (or injuries). The decision to obtain

radiographs is based on clinical findings. A radiograph is not

indicated for an isolated simple nasal fracture. (Courtesy of David

W. Munter, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Septal

Hematoma A bluish, grapelike

mass on the nasal septum. If untreated, this can result in septal

necrosis and a saddle-nose deformity. An incision, drainage, and

packing are indicated. (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Nasal fractures may have

associated facial injuries—such as orbital, frontal sinus, or

cribriform plate fractures—and these more serious injuries must be

ruled out. A simple nasal contusion may present identically to a simple

nasal fracture with pain, swelling, and ecchymosis. A frontonasoethmoid

fracture has nasal or frontal crepitus and may have associated

telecanthus or obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Look for more serious injuries

first. Patients with associated facial bone deformity or tenderness may

require radiographs to rule out facial fractures. Nasal fractures rarely

require radiographs (Fig. 1.10). Obvious deformities are referred within

2 to 5 days for reduction, after the swelling has subsided. Nasal

injuries without deformity need only conservative therapy with an

analgesic and possibly a nasal decongestant. Septal hematomas must be

immediately drained, with packing placed to prevent reaccumulation. In

some cases, epistaxis may not be controlled by pressure alone and may

require nasal packing. Lacerations overlying a simple nasal fracture

should be vigorously irrigated and primarily closed with the patient

placed on antibiotic coverage. Complex nasal lacerations with underlying

fractures should be referred for closure. Nasal fractures with mild

angulation and without displacement may be reduced in the ED by

manipulating the nose with the examiner's thumbs into the correct

alignment.

|

|

|

|

|

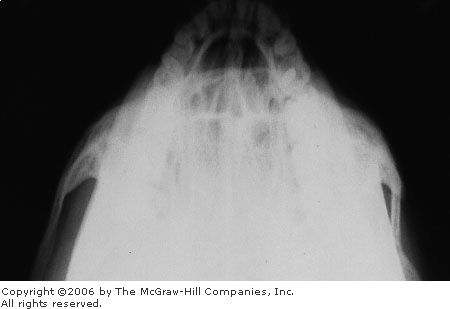

Nondisplaced

Nasal Fracture Radiograph of a

fracture of the nasal spine, for which no treatment other than ice

and analgesics is needed. This radiograph did not change the

treatment or disposition of the patient. (Courtesy of Lorenz F.

Lassen, MD.)

|

|

Clinical Pearls

1. Rule out any life threats or

serious associated injuries.

2. Control epistaxis to perform

a good intranasal examination. If there is no epistaxis or deformity,

treat the patient with ice and analgesics. If obvious deformity is

present, including a new septal deviation or deformity, treat with ice

and analgesics and provide ear/nose/throat (ENT) referral in 2 to 5 days for

reduction.

3. Although the effectiveness

of prophylactic antibiotics to prevent toxic shock syndrome is unproved,

every patient discharged with nasal packing should be placed on

antistaphylococcal antibiotics and referred to ENT in 2 to 3 days.

4. Consider cribriform plate

fractures in patients with clear rhinorrhea after nasal injury, with the

understanding that this finding may be delayed.

5. Check every patient for a

septal hematoma.

|

|

Fractures of the Zygoma

Associated Clinical Features

The zygoma bone has two major

components, the zygomatic arch and the body. The arch forms the inferior

and lateral orbit, and the body forms the malar eminence of the face.

Fractures to the zygoma are usually the result of blunt trauma. Direct

blows to the arch can result in isolated arch fractures (Fig. 1.11).

These present clinically with pain on opening the mouth secondary to the

insertion of the temporalis muscle at the arch or impingement on the

coronoid process. More extensive trauma can result in the "tripod fracture,"

which consists of fractures through three structures: the frontozygomatic

suture; the maxillary process of the zygoma including the inferior

orbital floor, inferior orbital rim, and lateral wall of the maxillary

sinus; and the zygomatic arch (Figs. 1.12, 1.13). Clinically, patients

present with a flattened malar eminence and edema and ecchymosis to the

area, with a palpable step-off on examination. Injury to the infraorbital

nerve may result in infraorbital paresthesia, and gaze disturbances may result

from injury to orbital contents. Subcutaneous emphysema may be caused by

a fracture of the antral wall at the zygomatic buttress.

|

|

|

|

|

Zygomatic

Arch Fracture Jug-handle view

of the zygomatic arch demonstrating a depressed fracture. In such a

case, operative reduction can be delayed for several days. (Courtesy

of Timothy D. McGuirk, DO.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Zygomatic

Fracture Patient with blunt

trauma to the zygoma. Flattening of the right malar eminence is

evident. (Courtesy of Edward S. Amrhein, DDS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tripod

Fracture The fracture lines

involved in a tripod fracture are demonstrated in this

three-dimensional CT reconstruction. The large defect in the frontal

area is artifact from the reconstruction. (Courtesy of Patrick W.

Lappert, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Other facial fractures, including

LeFort II and III fractures, may involve the zygoma bone or orbit. These

fractures typically involve more extensive facial trauma. Orbital blowout

fractures may present with entrapment and ocular injuries, but the malar

eminence appears normal.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Plain films, including a Waters

view and "jug-handle" view (a submental-vertex view of the

zygomatic arches), demonstrate the fracture and evaluate the

zygomaticomaxillary complex. In the case of a tripod fracture, facial CT

will best show the involvement and degree of displacement. Since plain

films often do not adequately demonstrate all elements of the fracture,

patients with evidence of a tripod fracture should have CT on an urgent

basis to help identify the extent of bony injuries. The CT results guide

the need for urgent referral. Simple zygomatic arch or tripod fractures

without eye injury can be treated with ice and analgesics and referred

for delayed operative consideration in 5 to 7 days. More extensive tripod

fractures or those with eye injuries should be referred more urgently.

Decongestants and broad-spectrum antibiotics are generally recommended

for tripod fractures, since the fracture crosses into the maxillary

sinus.

Clinical Pearls

1. Tripod fractures are often

associated with orbital and ocular trauma. Palpate the zygomatic arch and

orbital rims carefully for a step-off deformity.

2. Examine for eye findings

such as diplopia, hyphema, or retinal detachment. Check for infraorbital

paresthesia indicating injury or impingement of the second division of

cranial nerve V.

3. Visual inspection of the

malar eminence from several angles (especially by viewing the area from

over the head of the patient in the coronal plane, Fig. 1.12) allows

detection of a subtle abnormality.

4. Insist on adequate

radiographs of the zygomatic arches, which require good positioning of

the patient.

|

|

LeFort Facial Fractures

Associated Clinical Features

All LeFort facial fractures

involve the maxilla (Fig. 1.14). Clinically, the patient has facial

injuries, swelling, and ecchymosis (Figs. 1.15, 1.16). LeFort I fractures

are those involving an area under the nasal fossa. LeFort II fractures

involve a pyramidal area including the maxilla, nasal bones, and medial

orbits. LeFort III fractures, sometimes described as craniofacial dissociation,

involve the maxilla, zygoma, nasal and ethmoid bones, and the bones of

the base of the skull. Airway compromise may be associated with LeFort II

and III fractures. Physical examination is sometimes helpful in

distinguishing the three. The examiner places fingers on the bridge of

the nose and tries to move the central maxillary incisors with the other

hand. If only the maxilla moves, a LeFort I is present; movement of the

upper jaw and nose indicates a LeFort II; and movement of the entire

midface and zygoma indicates a LeFort III. Because of the extent of

LeFort II and III fractures, they may be associated with cribriform plate

fractures and CSF rhinorrhea. The force required to sustain a LeFort II

or III fracture is considerable, and associated brain or cervical spine

injuries are common.

|

|

|

|

|

LeFort

Fractures Illustration of the

fracture lines of LeFort I (alveolar), LeFort II (zygomatic maxillary

complex), and LeFort III (cranial facial dysostosis) fractures.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LeFort

Facial Fractures Clinical

photograph of patient with blunt facial trauma. Note the ecchymosis

and edema. This patient sustained a LeFort II/III fracture (a LeFort

II fracture on one side and a LeFort III on the other), and

associated intracranial hemorrhages. (Courtesy of Stephen Corbett,

MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LeFort

Facial Fractures Clinical

photograph of patient with blunt facial trauma. Patient demonstrates

the classic "dish face" deformity (depressed midface)

associated with bilateral LeFort III fractures. (Courtesy of Robert

Schnarrs, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

LeFort II and III fractures can

be difficult to distinguish, and combination LeFort fractures (e.g.,

LeFort II on one side and LeFort III on the other) are common. Tripod and

frontonasoethmoid fractures may be present in blunt facial trauma as

well.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Patients with associated facial

bone deformity or tenderness may require radiographs to rule out facial

fractures. Plain facial films will reveal the presence of facial

fractures but are less helpful in determining the type or extent. Head

and facial CT, including three-dimensional re-creations, offer much more

useful information. Management of LeFort I fractures may involve only

dental splinting and oral surgery referral, but management of LeFort II

and III fractures normally requires admission because of associated injuries

as well as definitive operative repair. Epistaxis may be difficult to

control in LeFort II and III fractures, in rare cases requiring

intraoperative arterial ligation.

Clinical Pearls

1. Attention should be focused

on immediate airway management, since the massive edema associated with

LeFort II and III fractures may quickly lead to airway compromise.

2. Nasotracheal intubation

should be avoided because of the possibility of intracranial passage.

3. Any serious facial trauma

may also be associated with cervical spine injuries.

4. Associated cranial injuries

are common and are best evaluated by CT.

5. If not recognized, an occult

CSF leak may result in significant morbidity. Suspected CSF leaks require

neurosurgical consultation.

6. The best diagnostic modality

for delineation of the extent of injuries is CT of the facial bones.

|

|

Orbital Blowout Fracture

Associated Clinical Features

Blowout fractures occur when the

globe sustains a direct blunt force. There are two mechanisms of injury.

The first is a true blowout fracture, where all energy is transmitted to

the globe. The spherical globe is stronger than the thin orbital floor,

and the force is transmitted to the thin orbital floor or medially

through the ethmoid bones, with the resultant fracture. The object

causing the injury must be smaller than 5 to 6 cm, otherwise the globe is

protected by the surrounding orbit. Fists or small balls are the typical

causative agents. This mechanism of injury is more likely to cause

entrapment and globe injury. The second mechanism of injury occurs when

the energy from the blow is transmitted to the infraorbital rim, causing

a buckling of the orbital floor. Entrapment and globe injury is less

likely with this mechanism of injury. Patients with blowout fractures have

periorbital ecchymosis and lid edema (Figs. 1.17, 1.18) but may sustain

eye injuries as well, including chemosis, subconjunctival hemorrhage, or

infraorbital numbness from injury to the infraorbital nerve. Other eye

injuries should be sought and ruled out with a careful physical

examination; they include corneal abrasion, hyphema, enophthalmos,

proptosis, iridoplegia, dislocated lens, retinal tear, retinal

detachment, and ruptured globe. If the inferior rectus muscle is extruded

into the fracture, it may become entrapped; upward gaze is then limited,

with resultant diplopia (Figs. 1.19, 1.20). Because of the communication

with the maxillary sinus, subcutaneous emphysema is common.

|

|

|

|

|

Orbital

Ecchymosis Sustained from

blunt trauma to the globe, with some of the force directed to the

inferior orbital rim. This patient presents with subtle signs only

(ecchymosis and swelling with no entrapment or eye injury) yet has

the classic signs on plain films (Figure 1.18). This patient

demonstrates that orbital floor fractures can present with subtle

physical findings. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

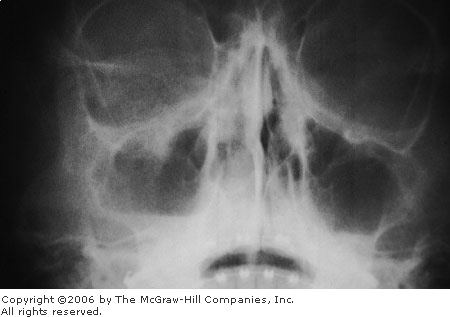

Blowout

Fracture Plain film

demonstrating a fracture of the floor of the right orbit, with a

teardrop sign due to extruded orbital contents. There is an

associated air-fluid level in the maxillary sinus due to blood. Note

the two lines seen at the inferior orbit: the infraorbital rim and

inferior floor of the orbit. These are well visualized on the

unaffected side but disrupted on the affected side. (Courtesy of

Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inferior

Rectus Entrapment The inferior

rectus muscle is entrapped within the blowout fracture. When the

patient tries to look upward, the affected eye has limited upward

gaze. The patient experiences diplopia with this maneuver. (Courtesy

of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

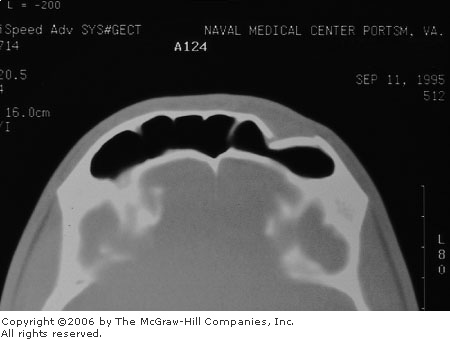

Blowout

Fracture with Entrapment CT of

the patient in Fig. 1.19 demonstrating the entrapped muscle extruding

into the maxillary sinus. (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Orbital contusions present with

similar physical findings. Fractures of the orbital rim are clinically

similar to orbital blowout fractures. Other facial fractures (zygoma,

tripod, LeFort) may involve the orbital floor but are associated with

more extensive injuries to the face outside of the orbit.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Plain radiography to include a

Caldwell view (showing orbital rim and walls) and a Waters view (orbital

floor and roof) demonstrates the fracture. Patients without eye injury or

entrapment may be treated conservatively with ice and analgesics and

referred for follow-up in 2 to 3 days. Patients with blood in the

maxillary sinus are usually treated with antibiotics. Strongly consider

an ophthalmology consultation in patients with a true blowout fracture

(all energy transmitted to the globe), since up to 30% of these patients

sustain a globe injury. Patients with entrapment should receive a CT of

the orbits and be referred on a same-day basis. Most specialists will

observe fractures with entrapment for 10 to 14 days to allow for

resolution of edema prior to operative repair.

Clinical Pearls

1. Enophthalmos, limited upward

gaze, diplopia with upward gaze, or infraorbital anesthesia from

entrapment or injury to the infraorbital nerve should heighten suspicion

of a blowout fracture.

2. Compare the pupillary level

on the affected side with the unaffected side, since it may be lower from

prolapse of the orbital contents into the maxillary sinus. Subtle

abnormalities may be appreciated as an asymmetric corneal light reflex

(Hirschberg's reflex).

3. Subcutaneous emphysema on

clinical examination, a soft-tissue teardrop along the roof of the

maxillary sinus on plain film, or an air-fluid level in the maxillary

sinus on plain film should also be interpreted as evidence of a blowout

fracture.

4. Some patients present with

unusual complaints—for example, of an eye swelling up after the

patient blows his or her nose (from subcutaneous emphysema) or air

bubbles emanating from the tear duct.

5. Carefully examine the eye

for visual acuity, hyphema, or retinal detachment. Remember to assess the

nose for a septal hematoma.

|

|

Mandibular Fractures

Associated Clinical Features

A history of blunt trauma,

mandibular pain, and possible malocclusion is normally seen with

mandibular fractures. A step-off in the dental line (Fig. 1.21) or

ecchymosis or hematoma to the floor of the mouth are often present.

Mandibular fractures may be open to the oral cavity, as manifest by gum

lacerations. Dental trauma may be associated. Other clinical features

include inferior alveolar or mental nerve paresthesia, loose or missing

teeth, dysphagia, trismus, or ecchymosis of the floor of the mouth

(considered pathognomonic) (Figs. 1.22, 1.23). Multiple mandibular

fractures are present in more than 50% of cases because of the ring-like

structure of the mandible. Mandibular fractures are often classified as

favorable or unfavorable, depending on the location and resultant

displacement forces exerted by the associated musculature. Those

fractures displaced by the masseter muscle are unfavorable (Fig. 1.24)

and inevitably require fixation, whereas fractures that are not displaced

by traction are favorable and in some cases will not require fixation.

Injuries creating unstable mandibular fractures may create airway

obstruction because the support for the tongue is lost. Mandibular

fractures are also classified based on the anatomic location of the

fracture (Fig. 1.25).

|

|

|

|

|

Open

Mandibular Fracture The open

fracture line is evident clinically. There is slight misalignment of

the teeth. (Courtesy of Edward S. Amrhein, DDS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sublingual

Hemorrhage Hemorrhage or

ecchymosis in the sublingual area is pathognomonic for mandibular

fracture. (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bilateral

Mandibular Fracture The

diagnosis is suggested by the bilateral ecchymosis seen in this

patient. (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Unfavorable

Mandibular Fracture Dental

panoramic view demonstrating a mandibular fracture with obvious

misalignment due to the distracting forces of the masseter muscle.

(Courtesy of Edward S. Amrhein, DDS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Classification

of Mandibular Fractures

Classification based on anatomic location of the fracture.

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Contusions have a similar

presentation and can be differentiated only radiographically. Dislocation

of the mandibular condyles may also result from blunt trauma and will

always have associated malocclusion, typified by an inability to close

the mouth. Isolated dental trauma may have a similar presentation, and

underlying mandibular fracture should be ruled out.

Emergency Department Disposition

and Treatment

The best view for evaluating

mandibular trauma is a dental panoramic view, which should be obtained if

available. Plain films should include anteroposterior (AP), bilateral

oblique, and Townes views to evaluate the condyles. Nondisplaced

fractures can be treated with analgesics, soft diet, and referral to oral

surgery in 1 to 2 days. Displaced fractures, open fractures, and

fractures with associated dental trauma need more urgent referral. All

mandibular fractures should be treated with antibiotics effective against

anaerobic oral flora (clindamycin, amoxicillin clavulanate) and tetanus

prophylaxis given if needed. The Barton's bandage has been suggested to

immobilize the jaw in the ED.

Clinical Pearls

1. The presence of disfiguring

facial injuries can be distracting. The primary consideration in the

evaluation of the patient with facial fractures is the assessment and treatment

of life-threatening injuries.

2. Any patient with trauma and

malocclusion should be considered to have a mandibular fracture.

3. The most sensitive sign of a

mandibular fracture is malocclusion. The jaw will deviate toward the side

of a unilateral condylar fracture on maximal opening of the mouth. A

nonfractured mandible should be able to hold a tongue blade between the

molars tightly enough to break it off. There should be no pain in

attempting to rotate the tongue blade between the molars.

4. Bilateral parasymphyseal

fractures may cause acute airway obstruction in the supine patient. This

is relieved by pulling the subluxed mandible and soft tissue forward and,

in patients in whom the cervical spine has been cleared, by elevating the

patient to a sitting position.

|

|

External Ear Injuries

Associated Clinical Features

Injuries to the external ear may

be open or closed. Blunt external ear trauma may cause a hematoma

(otohematoma) of the pinna (Fig. 1.26), which, if untreated, may result

in cartilage necrosis and chronic scarring or further cartilage formation

and permanent deformity ("cauliflower ear") (Fig. 1.27). Open

injuries include lacerations (with and without cartilage exposure) and

avulsions (Fig. 1.28).

|

|

|

|

|

Pinna

Hematoma A hematoma has

developed, characterized by swelling, discoloration, ecchymosis, and

flocculence. Immediate incision and drainage or aspiration is

indicated, followed by an ear compression dressing. (Courtesy of C.

Bruce MacDonald, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cauliflower

Ear Repeated trauma to the

pinna or undrained hematomas can result in cartilage necrosis and

subsequent deforming scar formation. (Courtesy of Timothy D. McGuirk,

DO.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Avulsed

Ear This ear injury, sustained

in a fight, resulted when the pinna was bitten off. Plastic repair is

needed. The avulsed part was wrapped in sterile gauze soaked with

saline and placed in a sterile container on ice. (Courtesy of David

W. Munter, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

These injuries are normally

self-evident. Pinna hematomas and contusions can sometimes be difficult

to distinguish, but flocculence is the hallmark of the hematoma.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Pinna hematomas must undergo

incision and drainage or large needle aspiration using sterile technique,

followed by a pressure dressing to prevent reaccumulation of the

hematoma. This procedure may need to be repeated several times; hence,

after ED drainage, the patient is treated with antistaphylococcal

antibiotics and referred to ENT or plastic surgery for follow-up in 24 h.

Lacerations must be carefully examined for cartilage involvement; if this

is present, copious irrigation, closure, and postrepair oral antibiotics

covering skin flora are indicated. Simple skin lacerations may be

repaired primarily with nonabsorbable 6-0 sutures. The dressing after

laceration repair is just as important as the primary repair. If a

compression dressing is not placed, hematoma formation can occur. Complex

lacerations or avulsions normally require ENT or plastic surgery

referral.

Clinical Pearls

1. Pinna hematomas may take

hours to develop, so give patients with blunt ear trauma careful

discharge instructions, with a follow-up in 12 to 24 h to check for

hematoma development.

2. Failure to adequately drain

a hematoma, reaccumulation of the hematoma owing to a faulty pressure

dressing, or inadequate follow-up increases the risk of infection of the

pinna (perichondritis) or of a disfiguring cauliflower ear.

3. Copiously irrigate injuries

with lacerated cartilage, which can usually be managed by primary closure

of the overlying skin. Direct closure of the cartilage is rarely

necessary and is indicated only for proper alignment, which helps lessen

later distortion. Use a minimal number of absorbable 5-0 or 6-0 sutures

through the perichondrium.

4. Lacerations to the lateral

aspect of the pinna should be minimally debrided because of the lack of

tissue at this site to cover the exposed cartilage.

5. In the case of an avulsion

injury, the avulsed part should be cleansed, wrapped in saline-moistened

gauze, placed in a sterile container, then placed on ice to await

reimplantation by ENT.

|

|

Frontal Sinus Fracture

Associated Clinical Features

Blunt trauma to the frontal area

may result in a depressed frontal sinus fracture. Often, there is an

associated laceration (Fig. 1.29). Isolated frontal fractures (Figs.

1.30, 1.31) normally do not have the associated features of massive blunt

facial trauma such as seen in LeFort II and III fractures. Careful nasal

speculum examination may reveal blood or CSF leak high in the nasal

cavity. Posterior table involvement can lead to mucopyocoele or epidural

empyema as late sequelae. Involvement of the posterior wall of the

frontal sinus may occur and result in cranial injury or dural tear.

|

|

|

|

|

Frontal

Laceration Any laceration over

the frontal sinuses should be explored to rule out a fracture. This

laceration was found to have an associated frontal fracture.

(Courtesy of David W. Munter, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frontal

Sinus Fracture Fracture defect

seen at the base of a laceration over the frontal sinus. (Courtesy of

Jeffrey Kuhn, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frontal

Sinus Fracture Fracture of the

outer table of the frontal sinus is seen under this forehead

laceration. (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Simple lacerations or contusions

of the frontal area may not involve fractures. Frontal fractures may be

part of a complex of facial fractures, as seen in frontonasoethmoid

fractures, but generally more extensive facial trauma is required.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Frontal sinus fractures revealed

on plain films of the frontal bones, including posteroanterior (PA),

lateral, and Waters views, may be quite subtle. The extent of the frontal

injury, especially posterior table involvement, is best investigated with

bone windows on CT (Fig. 1.32). Fractures involving only the anterior

table of the frontal sinus can be treated conservatively with referral to

ENT or plastic surgery in 1 to 2 days. Fractures involving the posterior

table require urgent neurosurgical referral. Frontal sinus fractures are

usually covered with high-dose antibiotics against both skin and sinus

flora (second- or third-generation cephalosporins). ED management also

includes control of epistaxis, application of ice packs, and analgesia.

|

|

|

|

|

Frontal

Sinus Fracture CT of the

patient in Figure 1.29 demonstrating a fracture of the anterior table

of the frontal sinus. (Courtesy of David W. Munter, MD.)

|

|

Clinical Pearls

1. Explore every frontal

laceration digitally before repair. Digital palpation is sensitive for

identifying frontal fractures, although false positives from lacerations

extending through the periosteum can occur.

2. Communication of irrigating

solutions with the nose or mouth indicates a breach in the frontal sinus.

3. For serious injuries, a CT

scan is mandatory to assess the posterior aspect of the sinus and for

possible intracranial injury.

|

|

Traumatic Exophthalmos

Associated Clinical Features

Normally the result of blunt

orbital trauma, the exophthalmos develops as a retrobulbar hematoma pushes

the globe outward. Patients present with periorbital edema, ecchymosis

(Fig. 1.33), a marked decrease in visual acuity, and an afferent

pupillary defect in the involved eye. The exophthalmos, which may be

obscured by periorbital edema, can be better appreciated from a superior

view (Fig. 1.34). Visual acuity may be affected by the direct trauma to

the eye, compression of the retinal artery, or, more rarely, neuropraxia

of the optic nerve.

|

|

|

|

|

Traumatic

Exophthalmos Blunt trauma

resulting in periorbital edema and ecchymosis, which obscures the

exophthalmos in this patient. The exophthalmos is not obvious in the

AP view and can therefore be initially unappreciated. Figure 1.34

shows the same patient viewed in the coronal plane from over the

forehead. (Courtesy of Frank Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Traumatic

Exophthalmos Superior view,

demonstrating the right-sided exophthalmos. (Courtesy of Frank

Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Periorbital ecchymosis and edema

can result from blunt trauma without a retrobulbar hematoma. Traumatic

chemosis can present with exophthalmos. Visual impairment can result from

retinal detachment, hyphema, globe rupture, or any number of nontraumatic

conditions. Nontraumatic exophthalmos can be caused by cavernous sinus

thrombosis, a complication of frontal sinusitis, or endocrine

(thyrotoxicosis) disorders.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

CT is the best modality to

determine the presence and extent of a retrobulbar hematoma and

associated facial or orbital fractures (Fig. 1.35). Referral to ENT and

ophthalmology is indicated on an urgent basis. An emergent lateral

canthotomy decompresses the orbit and can be performed in the ED.

Emergency treatment can be sight-saving.

|

|

|

|

|

Retrobulbar

Hematoma CT of the patient in

Figs. 1.33 and 1.34 with right retrobulbar hematoma and traumatic

exophthalmos. (Courtesy of Frank Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

Clinical Pearls

1. The retrobulbar hematoma and

resultant exophthalmos may not develop for hours. Give careful discharge

instructions to any patient with periorbital trauma.

2. Perform a careful ophthalmic

examination including visual acuity, since associated conditions such as

hyphema or retinal detachment are common.

3. A subtle exophthalmos may be

detected by looking down over the head of the patient and viewing the eye

from the coronal plane.

4. Lateral canthotomy is

indicated for emergent treatment of patients with traumatic exophthalmos

who demonstrate profound ischemic signs and symptoms of an afferent

pupillary defect and decreased vision.

5. An afferent pupillary defect

in a patient with blunt trauma to the face or eye with normal visual

acuity may be pharmacologically induced.

|

|