|

Note: Large images and

tables on this page may necessitate printing in landscape mode.

Copyright

©2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved.

Emergency

Medicine Atlas > Part 1. Regional

Anatomy > Chapter 10. Gynecologic and Obstetric

Conditions > Gynecologic Conditions >

|

Vaginitis

Associated Clinical Features

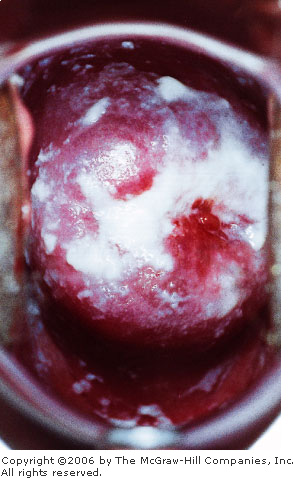

Candidal vaginitis is

characterized by a thick, curdy, white discharge (Fig. 10.1) and vulvar

discomfort. Intense vulvar erythema, pruritus, or burning are often

present. A microscopic slide prepared with 10% potassium hydroxide

yielding characteristic branch chain hyphae and spores establishes the

diagnosis (Fig. 21.16). The pH of the discharge is less than 4.5.

Predisposing factors that should be considered include oral

contraceptive, antibiotic, or corticosteroid use; pregnancy; and

diabetes. Sexually transmitted diseases are not usually associated with

isolated candidal vaginitis.

|

|

|

|

|

Candidal

Vaginitis Thick, curdy white

discharge secondary to candidal vaginitis. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop,

MS, MD.)

|

|

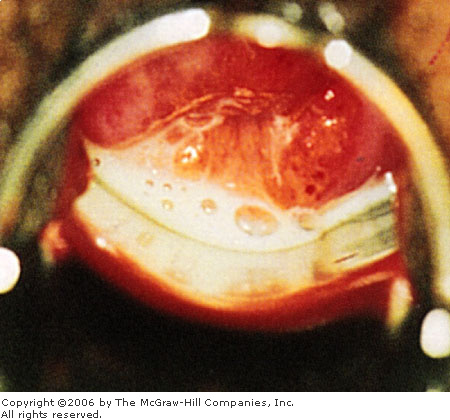

Trichomonas vaginitis presents as a

persistent, thin, copious discharge that is often frothy (Fig. 10.2),

green, or foul-smelling. The pH of these secretions is greater than 4.5.

The amount of vaginal and cervical erythema and inflammation varies

considerably; thus the diagnosis depends on the presence of motile

flagellates on normal saline wet-mount microscopy. Occasionally, multiple

petechiae on the vaginal wall (strawberry spots) or cervix (strawberry

cervix) are seen.

|

|

|

|

|

Trichomonas

Vaginitis Thin vaginal discharge suggestive of Trichomonas

vaginitis. (Courtesy of H. Hunter Handsfield: Atlas of Sexually

Transmitted Diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1992.)

|

|

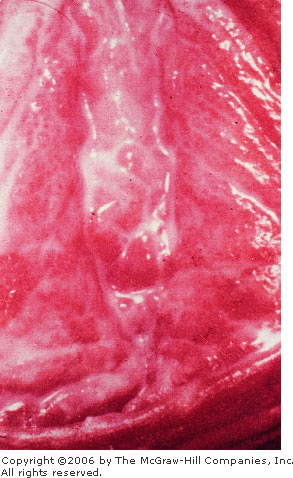

Bacterial vaginosis (previously termed Haemophilus

or Gardnerella vaginitis) is characterized by a malodorous,

homogeneous discharge (Fig. 10.3) with a pH greater than 4.5 and a

transient amine (fishy) odor when mixed with a drop of KOH solution

(positive sniff test). The presence of clue cells on normal saline wet

mount establishes the diagnosis (Fig. 21.13). Other associated vaginal or

abdominal complaints are minimal and, if significant, may represent

another disease process.

|

|

|

|

|

Gardnerella Vaginitis

Thin, milky white discharge suggestive of Gardnerella

vaginitis. (Courtesy of Curatek Pharmaceuticals.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Vaginal foreign bodies,

especially in prepubescent girls, may present with a heavy white

discharge but would be unaccompanied by vulvar erythema or the

microscopic appearance of hyphae. Atrophic vaginitis is commonly found in

postmenopausal women and is distinguished from candidal vaginitis by

mucosal dryness, atrophy, dyspareunia, minimal discharge, and itching.

Other considerations include contact dermatitis, local irritation secondary

to tight-fitting underwear, and contact dermatitis from toiletry items.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

For candidal vaginitis,

various regimens of topical antifungal agents are the mainstay of

treatment (clotrimazole 1% cream, one applicatorful inserted high into

the vaginal vault for 7 nights, clotrimazole, two 100-mg vaginal tablets

for 3 nights or one 500-mg vaginal tablet for single-dose treatment).

Oral fluconazole (Diflucan, 150 mg as a single dose) is also effective.

Nystatin vaginal tablets (100,000 U daily for 2 weeks) are generally

considered safe for use in the first trimester of pregnancy.

For Trichomonas vaginitis,

a single, one-time dose of metronidazole (2 g) is generally curative.

Alternatively, 500 mg given twice daily can be used for recurrent or

refractory cases. Metronidazole is contraindicted in pregnancy and is

associated with an Antabuse-like reaction when taken with alcohol. For

the pregnant patient, clotrimazole (100-mg vaginal suppositories daily

for 7 to 14 days) may provide symptomatic relief.

For bacterial vaginosis, metronidazole

(500 mg twice daily for 7 days) is recommended in the nonpregnant

patient. Amoxicillin (500 mg tid for 7 days) or clindamycin (300 mg bid)

for 7 days is a safe but less effective alternative during pregnancy.

Treatment for asymptomatic infection or for male sexual partners is not

generally recommended.

Clinical Pearls

1. Diabetes mellitus or

immunosuppression should be considered in refractory or recurrent cases

of candidal vaginitis.

2. A history of balanitis in

the sexual partner should be sought and treated if present.

3. Trichomonas should be

considered a sexually transmitted disease. It is generally recommended,

therefore, that concomitant culturing for gonorrhea and Chlamydia

be performed. Serologic testing for syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis B should

be considered.

4. Patients treated with

metronidazole should abstain from alcohol for the duration of treatment

and for at least 24 h after their last dose.

|

|

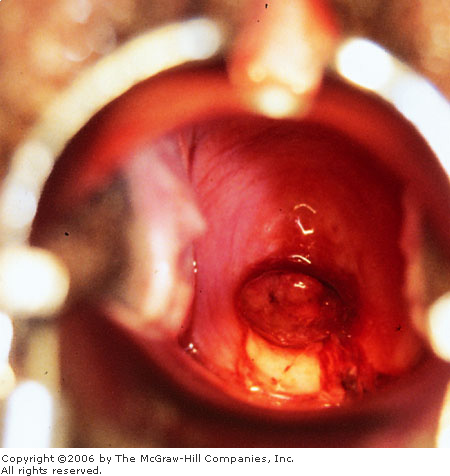

Mucopurulent Cervicitis

Associated Clinical Features

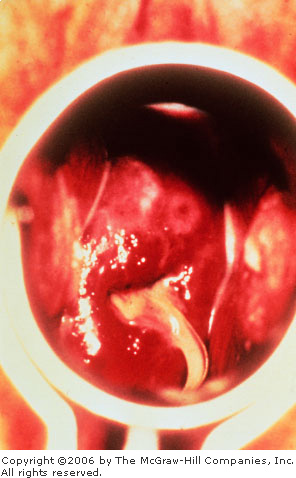

The patient's chief complaint is

often a purulent vaginal discharge. Speculum examination reveals a

purulent, viscous discharge emanating from the cervical os (Fig. 10.4).

Otherwise, a purulent discharge may be seen on a cervical swab. A Gram's

stain may reveal either gram-negative intracellular diplococci consistent

with Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Fig. 21.11) or be nonspecific,

consistent with Chlamydia trachomatis, a coinfectant with the

gonococcus about 50% of the time. The diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory

disease should be considered, when accompanied by symptoms of lower

abdominal pain and signs of pelvic peritonitis such as cervical motion

and adnexal tenderness.

|

|

|

|

|

Mucopurulent

Cervicitis Viscous, opaque

discharge emanating from the cervical os, consistent with

mucopurulent cervicitis. The string from an intrauterine device is

seen descending through the os in this patient. (Courtesy of Sue

Rist, FNP.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Physiologic cervical mucous

discharge at the time of ovulation may occur but is generally clear, with

few white blood cells on Gram's stain.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Cultures for Chlamydia

trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae should be obtained prior to

initiation of therapy. Ceftriaxone (125 mg as a single intramuscular

dose) provides coverage for N. gonorrhoeae. Single-dose oral

quinolones (ciprofloxacin, 500 mg, or ofloxacin, 400 mg) can be used in

penicillin-allergic patients. Doxycycline (100 mg) or ofloxacin (300 mg)

bid for 7 days or a single 1-g dose of azithromycin provides coverage for

Chlamydia. Erythromycin (base 500 mg qid for 7 days) is the

alternative for pregnant patients.

Clinical Pearls

1. The discharge of candidal,

trichomonal, or Gardnerella vaginitis is almost never limited

solely to the cervix.

2. Mucopurulent cervicitis is

almost always secondary to a sexually transmitted disease; thus sexual

partners should be treated as well.

3. Refer all patients for

formal gynecologic follow-up after culture and treatment, since early

cervical neoplasia may have a similar appearance.

|

|

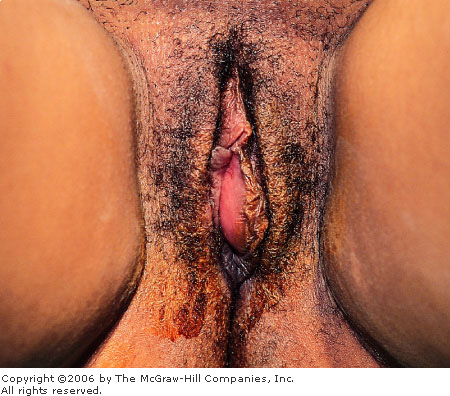

Bartholin's Gland Abscess

Associated Clinical Features

Bartholin's glands and ducts are

located over the lower third of the introitus near the labia minora. A

cyst or abscess can result from an obstructed duct, which usually occurs

secondary to scarring from trauma, delivery, or episiotomy. Infection of

the cyst is usually with mixed vaginal or fecal flora (Escherichia

coli) but may also contain Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia

trachomatis. Progressive enlargement and infection lead to increasing

pain, swelling, and dyspareunia. A tender, fluctuant cystic mass with

surrounding labial edema is easily appreciated on examination (Fig.

10.5).

|

|

|

|

|

Bartholin's

Gland Abscess Typical

appearance of a Bartholin's gland abscess with the labial fluctuance

pointing medially. (Courtesy of the Medical Photography Department,

Naval Medical Center, San Diego, CA.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Epidermal inclusion cysts and

sebaceous cysts of the labia majora may look similar but are generally

smaller. When they are inflamed or infected, maximal fluctuance generally

points toward the external aspect of the labium, as opposed to

Bartholin's gland cysts, which point medially. Occlusion and infection of

apocrine sweat glands can lead to subcutaneous abscess

formation—known as hidradenitis suppurativa. Vulvar hematoma,

leiomyoma, lipoma, and fibromas may occasionally be confused with a

noninfected Bartholin's cyst. Vulvar cancer usually arises in

postmenopausal women and is generally either ulcerated, excoriated, or

exophytic.

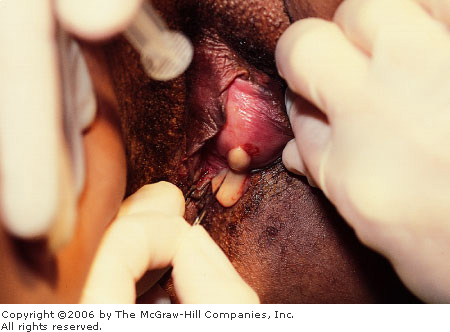

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Simple incision and drainage

(Fig. 10.6) followed by sitz baths provide the most effective and

expeditious relief on an emergency basis. Unfortunately, reocclusion and

reaccumulation of cystic swelling are common. Definitive therapy of

recurrent Bartholin's gland cysts involves marsupialization by suturing

the introital mucosa to the inner cyst wall.

|

|

|

|

|

Bartholin's

Gland Abscess Medial incision

of the cyst yielding purulent fluid, consistent with a Bartholin's

gland abscess. (Courtesy of the Medical Photography Department, Naval

Medical Center, San Diego, CA.)

|

|

Clinical Pearls

1. Antibiotics, although

commonly used, are usually not required.

2. Placement of a Word catheter

into the cyst cavity (Fig. 10.7) decreases the incidence of reocclusion,

but it must be allowed to remain in place for up to 6 weeks to ensure

epithelialization of the drainage tract.

|

|

|

|

|

Bartholin's

Gland Abscess Insertion and

inflation of a Word catheter into the cyst cavity. The free end of

the catheter can be tucked into the vagina for long-term placement,

allowing for epithelialization of the incision site. (Courtesy of the

Medical Photography Department, Naval Medical Center, San Diego, CA.)

|

|

|

|

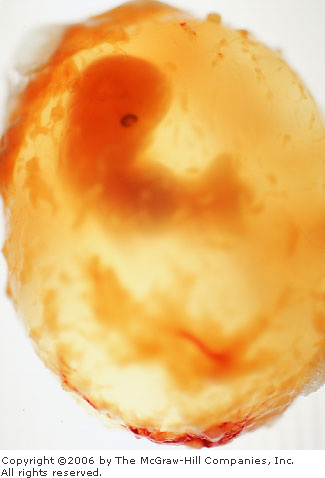

Spontaneous Abortion

Associated Clinical Features

Spontaneous abortion is

associated with vaginal bleeding and abdominal discomfort. Severe pain,

heavy bleeding with the passage of clots or tissue (Fig. 10.8), and

hypotension may also be present. Threatened abortion is diagnosed

when mild cramping and vaginal bleeding are not accompanied by the

complete or partial extrusion of tissue, cervical dilation, or ectopic

pregnancy. Uterine cramping with progressive dilation of the cervix, with

or without partial extrusion of the products of conception, indicates the

presence of an inevitable abortion (Fig. 10.9). In an incomplete

abortion, some elements of the conceptus have passed, yet retained

intrauterine tissue leads to ongoing uterine cramping, cervical dilation,

and persistent bleeding.

|

|

|

|

|

Spontaneous

Abortion Passage of tissue in

a spontaneous abortion at 4 weeks. (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack,

MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spontaneous

Abortion Dilation of the

cervical os with partial extrusion of tissue in the setting of an

inevitable abortion. (Courtesy of Robert Buckley, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Ectopic pregnancy should be

considered in all first-trimester females with lower abdominal pain or

vaginal bleeding. The presence of frank tissue passage or cervical

dilation essentially excludes this diagnosis. Large blood clots or an

intrauterine decidual cast (Fig. 10.10), however, may occasionally be

mistaken for products of conception.

|

|

|

|

|

Decidual

Cast A decidual cast or

organized clot may occasionally be mistaken for products of conception.

(Courtesy of the Medical Photography Department, Naval Medical

Center, San Diego, CA.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Intravenous access, fluid

resuscitation, cross-matching of blood, and urgent gynecologic

consultation should be implemented in the presence of severe pain, heavy

bleeding, or hypovolemia. All tissue should be sent to pathology for

definitive identification. Occasionally, patients who initially have an

open cervical os will rapidly expel the remaining products of conception,

with subsequent resolution of all pain and bleeding. These patients may

be discharged from the ED with the diagnosis of completed abortion if

otherwise clinically stable. Anti-Rh immunoglobulin (RhoGAM) should be

administered in all cases of vaginal bleeding in the pregnant patient

where the mother is Rh-negative and the father is Rh-positive.

Clinical Pearls

1. The passage of large clots

usually indicates rapid heavy bleeding.

2. Completed abortion is

characterized by the passage of tissue, followed by resolution of

bleeding and closure of the cervical os.

3. Fever, leukocytosis, pelvic

tenderness, and malodorous cervical discharge should suggest septic

abortion.

|

|

Genital Trauma and Sexual Assault

Associated Clinical Features

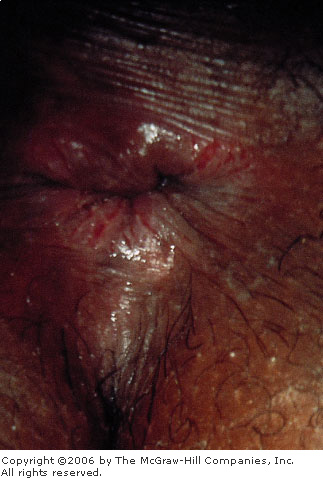

Patients who present for

examination and treatment following an incident of sexual assault are

ideally cared for by a multidisciplinary team capable of addressing the

immediate medical and psychosocial needs of the patient in concert with

forensic and legal requirements. A thorough general examination may

reveal associated contusions and other soft tissue injuries. A meticulous

inspection of the perineum, rectum, vaginal fornices, vagina, and cervix

is required to identify inflicted injuries. Toluidine staining and colposcopy

are often useful in enhancing less apparent injuries such as those to the

posterior fourchette following sexual assault (Fig. 10.11). These are

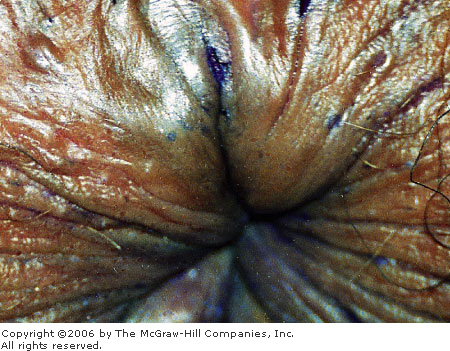

most commonly found between the 3 and 9 o'clock distribution when the

patient is examined in the dorsal lithotomy position. Perianal

lacerations (Fig. 10.12) may also be seen as toluidine-enhanced linear

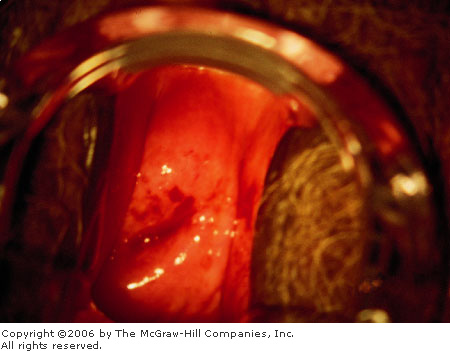

tears (Fig. 10.13). Examination of the cervix and posterior vaginal vault

may reveal injuries to those structures (Fig. 10.14).

|

|

|

|

|

Genital

Trauma (Posterior Fourchette)

Linear tears to the posterior fourchette—due to sexual

assault—enhanced by toluidine staining. (Courtesy of Hillary J.

Larkin, PA-C, and Lauri A. Paolinetti, PA-C.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Genital

Trauma (Perianal) Perianal

lacerations following sexual assault. (Courtesy of Hillary J. Larkin,

PA-C, and Lauri A. Paolinetti, PA-C.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Genital

Trauma (Toluidine Staining)

Toluidine staining showing subtle perianal lacerations following

forceful anal penetration. (Courtesy of Aurora Mendez, RN.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Genital

Trauma (Cervix) Cervical

trauma in an elderly victim of sexual assault. Petechiae and freshly

bleeding abrasions are noted from 10 to 3 o'clock. (Courtesy of

Hillary J. Larkin, PA-C, and Lauri A. Paolinetti, PA-C.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Perineal injuries from accidental

trauma may be indistinguishable from those of sexual assault and should

be interpreted in the context of the history. The assessment of assault

or rape is technically a legal one; therefore the examiner should be

careful to document the medical appearance of the wounds rather than

speculate as to the specific mechanism by which each injury occurred.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment is preceded by forensic

evidence gathering, consisting of a Wood's lamp examination to identify

semen for collection, pubic hair sampling and combing, vaginal and

cervical smears (air-dried), a cervical and vaginal wet mount to identify

sperm, vaginal aspirate to test for acid phosphatase, and rectal or

buccal swabs for sperm. A prepackaged kit with directions may be

available to facilitate the collection of evidence.

Cervical cultures for Chlamydia

and Neisseria gonorrhoea should be obtained as well as serum

testing for syphilis, hepatitis, and HIV. Empiric antibiotic coverage

against sexually transmitted diseases should be provided and an oral

contraceptive offered (after confirming a nonpregnant state) to prevent

unwanted pregnancy.

Clinical Pearls

1. The medical care of the patient

who has been sexually assaulted should ideally be performed by

experienced supportive staff familiar with the details of forensic

evidence gathering and colposcopic photography.

2. Normal findings on physical

examination and no sperm on wet preparation do not exclude the

possibility of assault.

|

|

Uterine Prolapse

Associated Clinical Features

Uterine prolapse is defined as

the propulsion of the uterus through the pelvic floor or vaginal

introitus. In first-degree prolapse, the cervix descends into the lower

third of the vagina; in second-degree prolapse, the cervix usually

protrudes through the introitus; whereas in third-degree prolapse, or

procidentia, the entire uterus is externalized with inversion of the

vagina (Fig. 10.15). Symptoms include a sensation of inguinal traction,

low back pain, urinary incontinence, and the presence of a vaginal mass.

|

|

|

|

|

Third-Degree

Uterine Prolapse Note the

protrusion of the entire uterus with cervix visible through the

vaginal introitus. (Courtesy of Matthew Backer, Jr., MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Uterine prolapse can occasionally

be confused with a cystocele, enterocele, or soft tissue tumor. These

disorders, which may all be accompanied by introital bulging, are easily

distinguished by the absence of cervicouterine descent.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Patients with first- or

second-degree prolapse should be referred to a gynecologist for pessary

placement or surgical correction. With procidentia, the uterus should be

manually reduced into the vaginal vault and the patient placed at bed

rest until evaluated by a gynecologic consultant.

Clinical Pearl

1. With procidentia, the

exposed uterus is prone to abrasion and possible secondary infection.

|

|

Cystocele

Associated Clinical Features

A cystocele occurs when there is

relaxation and bulging of the posterior bladder wall and trigone into the

vagina (Fig. 10.16) and is usually due to birth trauma. Patients complain

of bulging or fullness over the introitus that is worsened with Valsalva

(Fig. 10.17) and relieved with recumbency. It is often associated with

urinary incontinence or symptoms of incomplete emptying. Most cystoceles,

however, are asymptomatic. Examination reveals a thin-walled bulging of

the anterior vaginal wall, which, in severe cases, may pass through the

introitus with Valsalva.

|

|

|

|

|

Cystocele Cystocele with bulging of the posterior

bladder wall into the vagina. (Courtesy of Matthew Backer, Jr., MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cystocele Cystocele worsening with Valsalva. (Courtesy

of Matthew Backer, Jr., MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

An enterocele may lead to a

similar bulging of the anterior vaginal wall but is much less common and

is generally limited to those patients who have had a hysterectomy.

Rectocele, uterine prolapse, and soft tissue tumors should also be

considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Larger cystoceles or those

associated with urinary symptomatology, pain, or bothersome bulging

should be referred to a gynecologist for further evaluation.

Clinical Pearl

1. Most cystoceles are

asymptomatic and are detected incidentally at the time of pelvic

examination.

|

|

Rectocele

Associated Clinical Features

Most small rectoceles are

completely asymptomatic, though symptoms of introital bulging,

constipation, and incomplete rectal evacuation may occur. Bulging of the

introitus can be seen grossly on physical examination (Fig. 10.18) and

can become worse with Valsalva (Fig. 10.19). Rectovaginal examination

reveals a thin-walled protrusion of the rectovaginal septum into the

lower part of the vagina.

|

|

|

|

|

Rectocele This is characterized by bulging of the

posterior vaginal wall at the introitus. (Courtesy of Matthew Backer,

Jr., MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rectocele Worsening of the rectocele with Valsalva.

(Courtesy of Matthew Backer, Jr., MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Cystocele, enterocele, uterine

prolapse, and soft-tissue tumors should all be easily distinguished by

careful inspection.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Supportive measures with

hydration, laxatives, and stool softeners are generally all that is

needed to relieve the patient's symptoms. Those patients with large

symptomatic rectoceles who do not desire further childbearing are

candidates for posterior colpoperineorrhaphy.

Clinical Pearl

1. A rectocele is the

herniation of the rectovaginal wall and is usually due to childbirth.

|

|

Imperforate Hymen

Associated Clinical Features

The hymen is a membrane visible

at the introitus that separates the vestibule externally from the vagina

internally. The opening of the hymen can take on a variety of

shapes—annular, semilunar, cribiform, and septate. The congenital

absence of a hymenal orifice is called an imperforate hymen (IH). This

condition may become evident in infants or young children as a smooth,

glistening, protruding membrane due to the buildup of vaginal secretions

known as a mucocolpos. More commonly, an imperforate hymen presents in

adolescent girls with primary amenorrhea and recurrent abdominal pain.

The buildup of menstrual blood and secretions behind the hymen is called

hematocolpos and may become large enough to cause urinary retention by

pressing on the bladder neck.

Physical examination reveals a

smooth, dome-shaped, bluish-red bulging membrane (Fig. 10.20). A large,

smooth, cystic mass can often be palpated anteriorly on digital rectal

examination. Occasionally, the buildup of blood may spill over through

the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity, resulting in signs of

pelvic or abdominal peritonitis.

|

|

|

|

|

Imperforate

Hymen A bulging mass at the

introitus is seen in this patient with abdominal distention and

amenorrhea. The imperforate hymen was diagnosed, with subsequent

incision and drainage of the hematocolpos. (Courtesy of Mark Eich,

MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

A complete transverse septum,

located in the midvagina, presents similarly to IH but is generally not

visible to simple inspection. Partial and complete vaginal agenesis may

be confused with IH in preadolescents. Both cystocele and rectocele

present as bulging masses at the introitus (see Figs. 10.16, 10.18) but

occur almost exclusively in multiparous women, thus excluding IH from

consideration. The presentation of a bulging membrane at the introitus

may be briefly confused with a bulging amniotic sac—history and

abdominal examination, however, should allow this possibility to be

quickly excluded.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Imperforate hymen as well as

other abnormalities of the vaginal outlet should be referred to a

gynecologist for definitive treatment. This includes incision of the

hymen to allow drainage of the hematocolpos. Those instances detected in

preadolescence should ideally be referred to a practitioner who

specializes in pediatric cases.

Clinical Pearl

1. An imperforate hymen

presents in adolescent girls with primary amenorrhea and recurrent

abdominal pain.

|

|

Ectopic Pregnancy: Ultrasonographic Imaging

Associated Clinical Features

Ectopic pregnancy is the leading

cause of maternal obstetric morbidity in the first trimester of

pregnancy. Presentations commonly include mild vaginal bleeding and lower

abdominal pain, but patients can present in shock secondary to massive

hemorrhage. The menstrual history, although often unreliable, may reveal a

missed or recent abnormal menses. The presence of early signs of

pregnancy (breast changes, morning sickness, fatigue) is variable. On

examination, the uterus may be slightly enlarged, and adnexal tenderness

is not always present. The visualization of an intrauterine pregnancy

(IUP) by ultrasound (US) essentially excludes the diagnosis of ectopic

pregnancy, the exception being a rare dual pregnancy (IUP and ectopic).

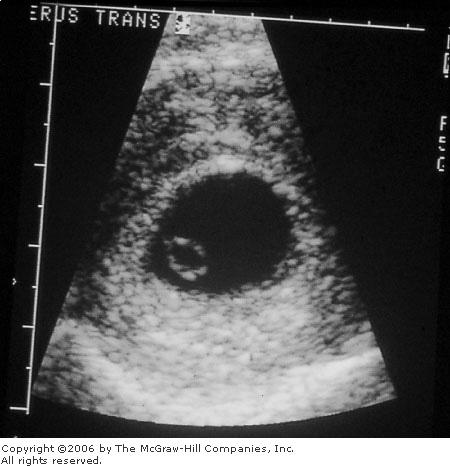

The appearance of a gestational sac at about 5 weeks (Fig. 10.21) is the

first significant finding on US suggestive of an IUP; however,

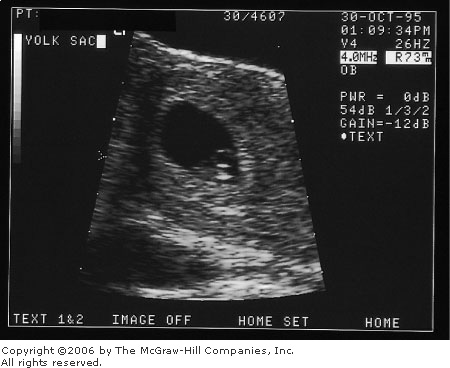

definitive diagnosis of IUP should be deferred until a yolk sac is

present (Fig. 10.22). A fetal pole develops next and can be seen on part

of the yolk sac (Fig. 10.23). The double decidual sac sign is evidence of

a true gestational sac and should be differentiated from the

pseudogestational sac formed from a decidual cast in ectopic pregnancy

(Fig. 10.24). When no gestational sac is visualized ("empty

uterus") (Fig. 10.25), ectopic pregnancy cannot be distinguished

from an early IUP too small to be seen on US.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intrauterine

Gestational Sac Discrete ring

of an intrauterine gestational sac seen on transvaginal ultrasound.

No yolk sac is visualized. A double decidual sac sign is seen,

however, lending evidence of a true gestational sac versus a

pseudogestational sac formed from a decidual cast in ectopic

pregnancy. A thorough look in the adnexa is important in diagnosing

ectopic pregnancy when a gestational sac is the only finding.

(Courtesy of Janice Underwood.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intrauterine

Yolk Sac Discrete ring of an

intrauterine yolk sac within the gestational sac seen on transvaginal

ultrasound. Definitive diagnosis of IUP should be deferred until a

fetal pole is present in the sac. (Courtesy of Janice Underwood.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intrauterine

Fetal Pole Ultrasound image of

an intrauterine pregnancy with a fetal pole consistent with an 8-week

gestation. An umbilical cord can be seen interposed between the yolk

sac and the fetal pole. (Courtesy of Robert Buckley, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ectopic

Pregnancy Transvaginal

ultrasound image of a right ectopic pregnancy with a decidual

reaction in the uterus resembling a gestational sac, or

"pseudosac." Visualization of a pseudogestational, or

"single," sac sign could be consistent with an early

gestational sac or an ectopic pregnancy with a uterine decidual cast.

(Courtesy of Janice Underwood.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Empty

Uterus Transvaginal ultrasound

image of an apparently empty uterus. Ectopic pregnancy should be

strongly suspected if a transvaginal ultrasound reveals an empty

uterus in the setting of a serum quantitative hCG level above the

institution's discriminatory zone. (Courtesy of Janice Underwood.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Ectopic pregnancy should be

considered in all first-trimester females presenting to the emergency

department with either lower abdominal pain or tenderness or vaginal

bleeding. A spontaneously completed abortion with an empty uterine cavity

may lead to confusion if the beta human chorionic gonadotropin ( hCG)

level is elevated above the institution's or sonographer's discriminatory

zone [generally between 1000 and 2000 mIU/mL (Third International

Standard)] and clinical evidence for the passage of products of

conception is lacking. Alternative causes of first-trimester lower

abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding include threatened or incomplete

abortion, molar pregnancy, ruptured corpus luteum cyst, adnexal torsion,

urinary tract infection, appendicitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and

ureteral calculi. hCG)

level is elevated above the institution's or sonographer's discriminatory

zone [generally between 1000 and 2000 mIU/mL (Third International

Standard)] and clinical evidence for the passage of products of

conception is lacking. Alternative causes of first-trimester lower

abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding include threatened or incomplete

abortion, molar pregnancy, ruptured corpus luteum cyst, adnexal torsion,

urinary tract infection, appendicitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and

ureteral calculi.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Unstable patients require

aggressive resuscitation with fluid and blood followed by surgery. Stable

patients with an ultrasound diagnosis consistent with ectopic pregnancy

(Fig. 10.24) warrant immediate gynecologic consultation. Definitive

therapeutic options range from observation in asymptomatic patients with declining

hCG levels, traditional or laparoscopic surgery, to pharmacologic therapy

with methotrexate. Despite the diminished diagnostic accuracy of

ultrasound at lower levels (up to half of all ectopic pregnancies have a

serum hCG level less than 2000 mIU/mL), if there is a strong clinical

suspicion for ectopic pregnancy, gynecologic consultation should be

considered. Those patients in whom a normal IUP is visualized can be

safely discharged with early outpatient follow-up.

Clinical Pearls

1. Ectopic pregnancy should be

considered in all women of reproductive age presenting with vaginal

bleeding, abdominal pain or tenderness, or a missed menstrual period.

2. Failure to visualize an

intrauterine pregnancy by transvaginal ultrasonography by the time the

serum hCG level has reached approximately 1000 mIU/mL or by abdominal

ultrasound once it has reached a level of approximately 6000 mIU/mL is

highly suggestive of the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy.

3. The ability of ultrasound

and quantitative  hCG to

diagnose ectopic pregnancy is highly dependent on the resolution of the

machine, the skill of the examiner, and the hCG to

diagnose ectopic pregnancy is highly dependent on the resolution of the

machine, the skill of the examiner, and the  hCG

assay used. Thus, every institution and examiner must develop a specific

"discriminatory zone," the level of hCG

assay used. Thus, every institution and examiner must develop a specific

"discriminatory zone," the level of  hCG on

which to base diagnostic decisions. hCG on

which to base diagnostic decisions.

4. A decidual cast in the

uterus of an ectopic pregnancy may resemble a gestational sac of an

intrauterine pregnancy on ultrasound.

5. Consider ectopic pregnancy

in any female of reproductive age presenting with syncope.

|

|

Molar Pregnancy (Hydatidiform Mole)

Associated Clinical Features

Molar pregnancy is part of a

spectrum of gestational trophoblastic tumors that include benign

hydatidiform moles, locally invasive moles, and choriocarcinoma. The

classic clinical presentation is painless first- or early

second-trimester vaginal bleeding with a uterine size larger than the

estimated gestational age based on the last menstrual period. Additional

clinical findings include nausea and vomiting, though this is often

indistinguishable from that found in normal pregnancy.

Signs of preeclampsia in the

first trimester or early second trimester (hypertension, headache,

proteinuria, and edema), are highly suggestive of this diagnosis.

Hyperthyroidism can be found in roughly 5% of cases. Acute respiratory

distress may occur owing to embolization of trophoblastic tissue into the

pulmonary vasculature, thyrotoxicosis, or simply fluid overload.

Moles commonly produce serum hCG

levels greater than 100,000 mIU/mL. The diagnosis is made by ultrasound.

Figure 10.26 demonstrates the classic finding of multiple intrauterine

echoes with no fetus.

|

|

|

|

|

Molar

Pregnancy "Snowstorm"

pattern demonstrating multiple intrauterine echoes with no fetus is

seen on transvaginal ultrasonography in a patient with a molar

pregnancy. Serum  HCG

was > 180,000 mIU/mL. (Courtesy of Robin Marshall, MD.) HCG

was > 180,000 mIU/mL. (Courtesy of Robin Marshall, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Spontaneous abortion and ectopic

pregnancy are much more common that molar disease and can generally be

differentiated based on typical ultrasound findings accompanied by

markedly elevated serum hCG levels.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Gynecologic consultation for

dilatation and curettage (D & C) should be obtained in all cases. For

patients who are reliable for follow-up, suction curettage may be

performed in an outpatient setting when the uterine size is less than 16

weeks and there is no evidence of preeclampsia, hyperthyroidism, or

respiratory distress.

All cases must have close

outpatient monitoring of serum hCG levels to rule out the presence of

malignant gestational trophoblastic disease.

Clinical Pearls

1. All patients with

pregnancies of less than 20 weeks' gestation with clinical findings of

preeclampsia should have gestational trophoblastic disease ruled out.

2. A "snowstorm"

pattern on ultrasonography demonstrating multiple intrauterine echoes

with no fetus coupled with a high hCG level is typical of molar

pregnancy.

|

|

Third-Trimester Blunt Abdominal Trauma

Associated Clinical Features

Trauma is a major cause of maternal

and fetal mortality. In addition to the common injuries to a solid organ

and/or hollow viscus associated with blunt abdominal trauma, special

consideration should be given to the possibility of preterm labor,

fetal-maternal hemorrhage, uterine rupture, and, most importantly,

abruptio placentae. Abruptio placentae is defined as the premature

separation of the placenta from the site of uterine implantation. It is

found in up to 50% of major blunt trauma patients and up to 5% of those

with apparent minor injuries. There are generally signs of uterine

hyperactivity and fetal distress when significant placental detachment

occurs. Most patients have vaginal bleeding, although the margins of

detachment are above the cervical os in up to 20%, who therefore have

little or no vaginal bleeding. Laboratory evidence of a consumptive

coagulopathy is occasionally seen with significant abruption. Electronic

fetal monitoring is of paramount importance in all cases of significant

trauma in patients beyond 20 weeks' gestation. As the pregnancy

progresses toward term, a normal heart rate averages between 120 and 160

bpm. Rapid, frequent fluctuations in the baseline are characteristic of

normal "reactivity" (Fig. 10.27). The loss of this reactivity

can occur during a normal sleep cycle, following narcotic administration,

or, most importantly, in the setting of fetal hypoxia or distress (Fig.

10.28). Decelerations are transient reductions in the fetal heart rate.

Late decelerations begin after the contraction begins and return to

baseline well after it ends, with the nadir of the deceleration occurring

after the peak of the uterine contraction. Late decelerations should

suggest fetal hypoxia, especially when they are accompanied by a loss of

normal baseline beat-to-beat variability (Fig. 10.29). Variable

decelerations are characterized by deep, broad decreases in fetal heart

rate, often falling below 100 bpm (Fig. 10.30). They can occur slightly

before, during, or after the onset of a uterine contraction, hence the

term variable. Variable decelerations are caused by the transient

compression of the umbilical cord during a contraction and are rarely

associated with significant hypoxia or acidosis unless they are frequent

or prolonged. They are most commonly appreciated during the second stage

of labor, when forceful uterine compression transiently occludes the

umbilical cord as the infant is propelled through the birth canal.

|

|

|

|

|

Normal

Beat-to-Beat Variability (BBV)

A normal reactive fetal monitor strip showing a baseline heart rate

between 120 and 160 with fluctuations in the short- and long-term

heart rate. (Courtesy of Timothy Jahn, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Loss

of BBV Loss of beat-to-beat

variability (BBV) in the fetal heart rate, which may forewarn of

fetal distress. This same pattern may also be seen during a normal

sleep cycle or following maternal narcotic administration. (Courtesy

of Gerard Van Houdt, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Late

Deceleration The nadir of a

late deceleration always follows the peak of the uterine contraction

with the heart rate approaching the baseline after the completion of

the uterine contraction; this is suggestive of hypoxia. (Courtesy of

James Palombaro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Variable

Deceleration Variable

decelerations are due to cord compression. They are characterized by

a rapid onset and recovery and may occur slightly before, during, or

after the onset of the contraction. (Courtesy of John O. Boyle, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Another alternative cause of

bright red vaginal bleeding in the third trimester of pregnancy is

placenta previa. This can generally be differentiated from abruption by

the visualization of a low-lying placenta on ultrasound.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

An obstetrician should be consulted

immediately in all trauma patients beyond 20 weeks' gestation. Blood for

type- and cross-matching, complete blood count, prothrombin time (PT),

partial thromboplastin time (PTT), fibrinogen, and fibrin degradation

products or D-dimer should be obtained.

It is generally recommended that patients undergo continuous tocofetal

monitoring for a minimum of 4 h to rule out preterm labor or fetal

distress. Ultrasound is essential in visualizing placental abruption.

Indications for emergency cesarean section include placental abruption,

signs of ongoing fetal distress, or uncontrolled maternal hemorrhage.

Clinical Pearls

1. Ecchymotic markings imparted

by a significant blunt force (Fig. 10.31) are not always present on a

gravid abdomen; thus, a careful history of the mechanism of trauma and

associated complaints is essential.

2. Anti-Rh immunoglobulin

should be administered for all cases of significant third-trimester blunt

abdominal trauma if the mother is Rh-negative and the father is

Rh-positive.

|

|

|

|

|

Gravid

Abdomen A third-trimester

gravid abdomen with ecchymotic markings imparted by a significant

blunt force. Fetal assessment should occur simultaneously with

maternal resuscitation. (Courtesy of John Fildes, MD.)

|

|

|

|

Ferning Pattern of Amniotic Fluid

Associated Clinical Features

Patients beyond the 20th week of

pregnancy presenting with a history of uncontrolled leakage of fluid

should undergo sterile speculum examination to determine the presence of

amniotic fluid. The diagnosis of membrane rupture can be made by

observing the passage of fluid from the cervix or pooling in the vaginal

vault. Without gross evidence of rupture, secretions from the vaginal

vault can be placed on a slide and allowed to air dry. The characteristic

arborization, or ferning pattern (Fig. 10.32), is diagnostic of amniotic

fluid, thus rupture of the membranes. In addition, the secretions can be

applied to nitrazine paper. The pH of normal vaginal secretions generally

falls between 4.5 and 5.5, whereas amniotic fluid generally ranges

between 7.0 and 7.5, yielding a dark blue tint.

|

|

|

|

|

Ferning

Pattern The arborization

pattern found when a drop of amniotic fluid is allowed to air dry on

a microscope slide, known as ferning. (Courtesy of Robert Buckley, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Urinary incontinence is the most

common alternative diagnosis in a third-trimester patient who presents

with a history of possible membrane rupture. The passage of the cervical

mucous plug, known as bloody show, may rarely be confused with the

passage of amniotic fluid. Although a small, subclinical amniotic fluid

leak can never be completely excluded, the presence of an acid pH, the

absence of gross fluid in the vaginal vault, and ferning all point

against the diagnosis of membrane rupture.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

All patients with confirmed

ruptured fetal membranes should be admitted to the labor and delivery

area and the obstetric consultant notified, irrespective of the presence

or absence of uterine contractions. The greatest risk to the fetus before

37 weeks is preterm delivery. The fetus at term is at risk for infection

secondary to chorioamnionitis if the time from membrane rupture to

vaginal delivery exceeds 24 h.

Clinical Pearls

1. With a strong suspicion of

membrane rupture by history and no objective evidence of amniotic fluid

on examination, a large sterile pad may be placed on the perineum and the

patient reexamined after brief ambulation. This assumes the absence of

uterine contractions and the presence of a reactive fetal monitor strip.

2. Umbilical cord prolapse

should be excluded with a speculum examination in all cases of membrane

rupture.

|

|

Emergency Delivery: Imminent Vertex

Delivery—Crowning

Associated Clinical Features

The second stage of labor begins

when the cervix is fully dilated, allowing for the gradual descent of the

head toward the vaginal outlet. As the head approaches the perineum, the

labia begin to separate with each contraction and then recede once the

contraction subsides. Crowning is the term applied when the head

separates the labial margins without receding at the end of the

contraction (Fig. 10.33).

|

|

|

|

|

Crowning Descent of the fetal head with separation of

the labia is known as crowning and heralds imminent vertex delivery.

(Courtesy of William Leninger, MD.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The appearance of crowning

heralds imminent vaginal delivery. Equipment for delivery and neonatal

resuscitation should be brought to the bedside. Both the on-call

obstetric consultant and pediatrician should be notified while

preparations are being made for ED delivery.

Clinical Pearls

1. Primigravida patients may

still require multiple sets of contractions and pushing to fully expel

the head through the vaginal outlet.

2. If meconium secretions are

detected well before delivery, continuous electronic tocofetal monitoring

should be begun and the obstetric and pediatric consultants notified.

|

|

Emergency Delivery: Normal Delivery Sequence

Associated Clinical Features

A gravid female with regular

forceful contractions and the urge to strain (push) can present without

warning. Crowning may be present and heralds imminent vaginal delivery.

Important historical questions include the number of previous

pregnancies, a diagnosis of twin gestations, and whether there is a

history of prenatal care or complications. The presence of greenish brown

fetal stool, known as meconium, is associated with fetal hypoxia and is a

clinical indicator of fetal distress. Fetal bradycardia or late

decelerations (Fig. 10.29) may be present and are also evidence of fetal

distress.

Differential Diagnosis

Complications (discussed below)

should be considered when the progress of delivery is altered or when the

presenting part is something other than the occiput. Twin gestations

should be considered in all emergency deliveries and asked about early in

the history.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Intravenous access, oxygen, and

equipment for delivery and neonatal resuscitation (suction, oxygen,

warming light, etc.) are immediately obtained as preparation for the

impending delivery.

Delivery of the Head

As the vertex passes through the

vaginal outlet, extension of the head occurs, followed by the appearance

of the forehead and chin. Extension and delivery of the fetal head can be

facilitated by applying gentle pressure upward on the chin through the

perineum—known as the modified Ritgen maneuver (Fig. 10.34).

Simultaneously, the fingers of the other hand can be used to elevate the

scalp to help extend the head. Once the head has been delivered, the

occiput promptly rotates toward a left or right lateral position. At this

stage, the nuchal region should be swept to detect the presence of a

nuchal umbilical cord (see Fig. 10.45). Before the delivery of the

shoulders, the nasopharynx should be gently suctioned with a bulb syringe

to clear away any blood or amniotic debris. If thick meconium is present,

deeper and more thorough suctioning of the posterior pharynx and glottic

region should be accomplished with a mechanical suction trap, since

aspiration of thick meconium by the newborn can lead to pneumonitis and

hypoxia.

|

|

|

|

|

Modified

Ritgen Maneuver Modified

Ritgen maneuver: upward pressure is applied on the fetal chin through

the perineum. (Courtesy of William Leninger, MD.)

|

|

Delivery of the Shoulders

Delivery of the shoulders

generally occurs spontaneously with little manipulation. Occasionally,

gentle downward traction applied by grasping the sides of the head with

two hands eases the delivery of the anterior shoulder (Fig. 10.35). The

head can then be directed upward to permit the delivery of the posterior

shoulder (Fig. 10.36). Following delivery of both shoulders, the body and

legs are easily delivered. Attention is then directed toward the

immediate care of the newborn. The cord is doubly clamped and ligated

(Fig. 10.37) and inspected for three vessels: two umbilical arteries and

one umbilical vein (Fig. 10.38). The child's pediatrician should be

notified if a two-vessel umbilical cord is found at delivery. The newborn

is immediately placed under a warming lamp for drying and gentle

stimulation while being observed for signs of distress (heart rate <

100, limp muscle tone, poor color, weak cry).

|

|

|

|

|

Anterior

Shoulder Delivery Delivery of

the anterior shoulder is facilitated with downward traction.

(Courtesy of William Leninger, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Posterior

Shoulder Delivery Delivery of

the posterior shoulder with upward traction. (Courtesy of William

Leninger, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Clamping

the Cord The cord is clamped

immediately after delivery. (Courtesy of William Leninger, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Normal

Umbilical Cord Cross-sectional

view of the two arteries and single vein of a normal three-vessel

umbilical cord. (Courtesy of Jennifer Jagoe, MD.)

|

|

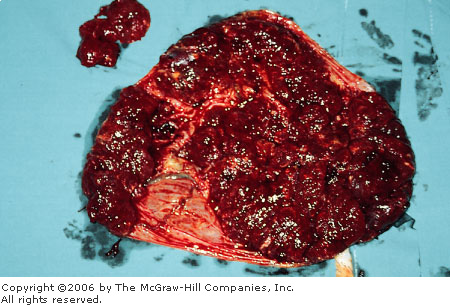

Delivery of the Placenta

Following delivery, gentle traction

can be placed on the cord while the opposite hand is used to massage the

uterine fundus (Fig. 10.39). The placenta will generally be delivered

within 15 to 20 min (Fig. 10.40) and should be grossly inspected.

Retention of small fragments should be suspected when inspection of the

placenta reveals evidence of a missing segment or cotyledon (Fig. 10.41).

The attending obstetric consultant should be notified, since retained

placental fragments often warrant manual exploration of the uterus,

especially in the context of persistent postpartum bleeding.

|

|

|

|

|

Placenta

Delivery Gentle traction is

applied to the cord while the opposite hand massages the uterus.

(Courtesy of William Leninger, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Placenta

Delivery Delivery of the

placenta. (Courtesy of William Leninger, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Placenta Placenta with a missing segment or cotyledon.

The missing placental tissue can be seen in the upper left-hand

corner of the photograph. (Courtesy of John O. Boyle, MD.)

|

|

Clinical Pearls

1. Both obstetric and pediatric

consultants should be alerted that preparations are being made for ED

delivery.

2. A two-vessel cord may be

found in about 1 in 500 singleton deliveries and is associated with an

increased incidence of congenital defects.

3. Retained placental fragments

should be considered in the setting of postpartum hemorrhage or

endometritis.

|

|

Umbilical Cord Prolapse in Emergency Delivery

Associated Clinical Features

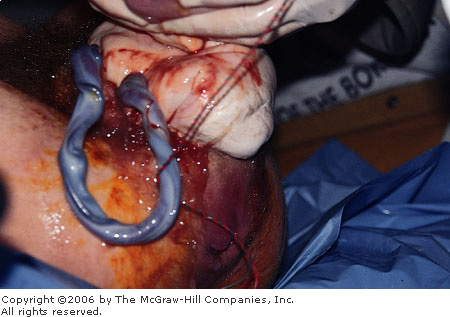

In an overt cord prolapse, a loop

of umbilical cord is visualized either at the introitus (Fig. 10.42) or

on speculum examination following membrane rupture (Fig. 10.43).

Alternatively, a small loop of cord may be palpated at the cervical os.

In a funic cord prolapse, a loop of umbilical cord is palpated directly

through intact fetal membranes. Occult prolapse occurs when the umbilical

cord descends between the presenting part and the lower uterine segment

but is not visible or directly palpable on examination. Intermittent

compression of the umbilical cord with each uterine contraction may be

detected by the presence of variable decelerations of the fetal monitor

(see Fig. 10.30). The new onset of variable decelerations should always

prompt immediate cervical examination to rule out an overt cord prolapse.

Severe persistent bradycardia may ensue if cord compression is sustained

beyond the duration of the contraction, which is often the case in an

overt prolapse.

|

|

|

|

|

Umbilical

Cord Prolapse Prolapsed

umbilical cord visible at the vaginal introitus in a patient with

twin gestations. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

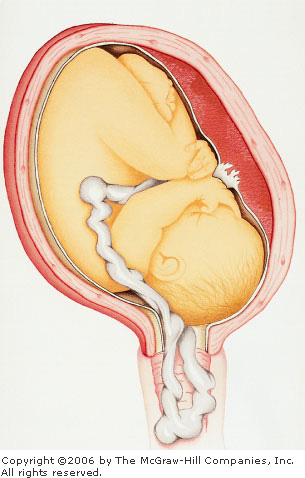

Umbilical

Cord Prolapse Schematic

drawing of an overt prolapse of the umbilical cord through a

partially dilated cervical os. (Courtesy of Judy Christensen.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Rarely, an inexperienced examiner

may mistake a presenting hand or foot for a prolapsed cord. This may be

clarified by careful digital or speculum examination.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Prolapse of the umbilical cord

presents an immediate threat to the fetal circulation and constitutes an

obstetric emergency. If an overt prolapse is detected in the ED, the

patient should immediately be placed in a knee-chest position and

continuous upward pressure applied by the examining hand to relieve the

pressure of the presenting part on the lower uterine segment. An

obstetrician should be summoned immediately and the patient taken

directly to the operating room for cesarean delivery. Continuous upward

pressure should be applied to the presenting part of the fetus at all

times during transport. Occasionally, precipitous vaginal delivery may

ensue in the ED shortly after a cord prolapse is detected. Resuscitative

equipment should be available in anticipation of a physiologically

compromised infant. If a funic prolapse is appreciated in the ED, an

obstetrician should be notified and the patient prepared for cesarean

delivery. Under no circumstance should the membranes be broken. Occult

prolapse is rarely appreciated in the ED.

Clinical Pearl

1. Pelvic examination to

exclude umbilical cord prolapse should be performed immediately following

rupture of membranes, the appearance of variable decelerations, or the

detection of bradycardia.

|

|

Breech Delivery

Associated Clinical Features

The incidence of singleton breech

presentation is approximately 3% but rises to higher than 20% in preterm

infants weighing less than 2000 g. In a frank breech, both hips are

flexed and both knees extended. In a complete breech, both hips and knees

are flexed, whereas a footling breech has one or both legs extended below

the buttocks. Frank breech is most common in full-term deliveries,

whereas footling presentation can be found in up to half of all preterm

deliveries. Breech deliveries carry a much higher mortality rate than

cephalic deliveries. Complications of breech delivery include umbilical

cord prolapse, nuchal arm obstruction, and difficulty in delivery of the

following head (Fig. 10.44).

|

|

|

|

|

Breech

Delivery Footling breech

vaginal delivery of the following head. (Courtesy of John O. Boyle,

MD.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The specific maneuvers for breech

extraction are beyond the scope of this text. If breech delivery appears

imminent, support and gentle traction should be applied as the various

parts spontaneously pass through the vaginal outlet, keeping in mind that

the biparietal diameter is greater than either the bitrochanteric or

bisacromial diameter.

Clinical Pearl

1. Immediate obstetric

consultation should be obtained in all breech deliveries.

|

|

Nuchal Cord in Emergency Delivery

Associated Clinical Features

The circumferential wrapping of

the umbilical cord around the child's neck occurs in about 20% of all

deliveries (Fig. 10.45). Tight approximation of the cord around the

infant's neck can lead to transient disruption of uterine blood flow

during contractions, leading to variable decelerations noted on the fetal

heart rate monitor (Fig. 10.30); it may also impede delivery once the

head passes through the introitus.

|

|

|

|

|

Nuchal

Cord A loose nuchal cord is

seen around the neck. (Courtesy of William Leninger, MD.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Once a cord is identified around

the neck, it should be slipped over the head using the index and middle

fingers. Occasionally two coils are identified.

Clinical Pearl

1. A loosely applied cord

should be pulled over the child's head. If the cord is wrapped too

tightly, it can be clamped and ligated on the perineum, followed by the

immediate delivery of the shoulders and body.

|

|

Shoulder Dystocia in Emergency Delivery

Associated Clinical Features

Shoulder dystocia is defined as

failure to deliver the shoulders, following delivery of the head, because

of impaction of the fetal shoulders against the pelvic outlet (Fig.

10.46). Risk factors include gestational diabetes, prior delivery of

large infants, and postterm delivery.

|

|

|

|

|

Shoulder

Dystocia Firm approximation of

the fetal head against the vaginal outlet consistent with shoulder

dystocia. (Courtesy of William Leninger, MD.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Shoulder dystocia is an acute

obstetric emergency, with the immediate life threat being asphyxia from

prolonged delivery. An obstetrician should be summoned immediately.

Equipment for neonatal resuscitation should be set up and, ideally, a

pediatric consultant should be summoned. In the absence of an obstetric

consultant, a wide episiotomy should be performed. The least invasive

maneuver is to forcefully flex the mother's knees toward her chest

(McRobert's maneuver). This extreme dorsal lithotomy position

occasionally allows for the appropriate engagement of the fetal

shoulders. If this is unsuccessful, a Wood's maneuver can be attempted by

hooking two fingers behind the infant's posterior scapula and rotating

the entire body in a screwlike manner. As the posterior shoulder rotates

upward, it can generally be delivered past the symphysis pubis. If the

Wood's maneuver fails to deliver the anterior shoulder, delivery of the

posterior arm may be attempted by inserting two fingers into the sacral

fossa and bringing down the entire posterior arm by flexing it at the

elbow. The remaining anterior shoulder should then deliver, either

spontaneously or else following rotation into the oblique position to

facilitate its delivery.

Clinical Pearls

1. Shoulder dystocia is an

acute obstetric emergency that requires quick action:

Call for help.

Cut a wide episiotomy.

Perform McRobert's maneuver.

Rotate the posterior shoulder.

2. After delivery, look for

fracture of the clavicles or humerus and possible brachial plexus injury.

|

|

Postpartum Perineal Lacerations

Associated Clinical Features

Lacerations to the perineum occur

commonly following a rapid, uncontrolled expulsion of the fetal head.

Postpartum perineal lacerations range from minor to severe.

Differential Diagnosis

Perineal lacerations due to birth

trauma are categorized into four groups. First-degree lacerations are

limited to the mucosa, skin, and superficial subcutaneous and submucosal

tissues (Fig. 10.47). Second-degree lacerations penetrate deeper into the

superficial fascia and transverse perineal musculature (Fig. 10.48). In

addition to these structures, a third-degree laceration disrupts the anal

sphincter, whereas a fourth-degree laceration extends into the rectal

lumen (Fig. 10.49).

|

|

|

|

|

First-Degree

Laceration First-degree

laceration limited to the mucosa, skin, and superficial subcutaneous

and submucosal tissues. There is no involvement of the underlying

fascia and muscle. (Courtesy of Jerry Van Houdt, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Second-Degree

Laceration There is disruption

of the hymenal ring and the deep perineal musculature, extending into

the vaginal mucosa and transversalis fascia, but no involvement of

the anal sphincter or mucosa. (Courtesy of Pamela Ambroz, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fourth-Degree

Laceration Fourth-degree

perineal laceration revealing wide separation of the perineal fascia

and anal sphincter. The examiner's small finger is in the rectal

lumen, showing extension of the tear proximally. (Courtesy of Timothy

Jahn, MD.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

In precipitous ED deliveries, the

repair of the episiotomy and/or perineal lacerations can often be

performed by the obstetric consultant, the details of repair being beyond

the scope of this book.

Clinical Pearl

1. Perineal laceration repair

fundamentally involves the sequential anatomic reapproximation, using

absorbable suture material, of the rectal mucosa, anal sphincter,

transverse perineal musculature, vaginal mucosa, and skin.

|

|