|

Note: Large images and

tables on this page may necessitate printing in landscape mode.

Copyright

©2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved.

Emergency

Medicine Atlas > Part 1. Regional

Anatomy > Chapter 12. Extremity Conditions >

|

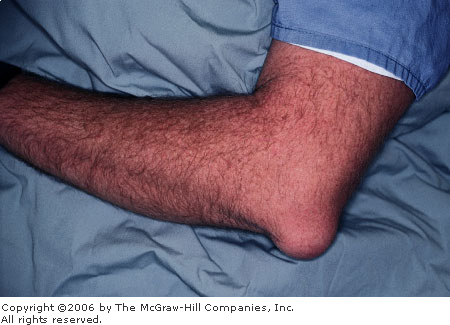

Cellulitis

Associated Clinical Features

Cellulitis is infection of the

skin or subcutaneous tissues from local invasion, traumatic wounds, or

hematogenous dissemination. The local inflammatory response is

characterized by erythema with poorly defined borders, edema, warmth,

pain, and limitation of movement (Fig. 12.1). Fever and constitutional

symptoms may be present and are commonly associated with bacteremia.

Trauma, lymphatic or venous stasis, immunodeficiency, and foreign bodies

are predisposing factors. There may be enlarged regional lymph nodes.

Organisms commonly causing cellulitis are group A beta hemolytic Streptococcus

and Staphylococcus aureus in nonintertriginous skin not associated

with an ulcer, gram-negative organisms in intertriginous skin and

ulcerations, and Haemophilus influenzae in children younger than 3

years. In immunocompromised hosts, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella

species, Enterobacter species, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa

may be the etiologic agents.

|

|

|

|

|

Cellulitis Cellulitis of the left leg characterized by

erythema and mild swelling. (Courtesy of Frank Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Deep venous thrombosis of the

lower extremities, erythema nodosum, septic or inflammatory arthritis,

osteomyelitis, herpes zoster, allergic reactions, arthropod envenomation,

and burns are included in the differential diagnosis of cellulitis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment of minor cases commonly

consists of immobilization, elevation, analgesia, and oral antibiotics

with reevaluation in 48 h. Admission and parenteral administration of

antibiotics may be necessary for immunocompromised or toxic-appearing

patients or those who do not initially respond to outpatient therapy.

Clinical Pearls

1. Aggressive treatment of

cellulitis with broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics in

immunocompromised patients (e.g., diabetes mellitus) is warranted.

2. Fever is uncommon and often

associated with bacteremia.

3. Radiography for the presence

of foreign body or gas in the tissue should be considered.

4. Leading-edge aspirates are

of low yield but may be of help in a toxic-appearing patient.

5. The incidence of Haemophilus

influenzae cellulitis in children has decreased significantly with

HIB vaccination.

|

|

Felon

Associated Clinical Features

A felon is a pyogenic infection

of the distal pulp space often caused by staphylococci or streptococci. A

felon cannot decompress itself because the collection of pus is trapped

between septa that attach the skin to the distal phalanx. This condition

is characterized by severe pain, exquisite tenderness, and tense swelling

of the distal pulp with erythema (Fig. 12.2). There may be a visible

collection of pus or palpable fluctuance. Complications include deep

ischemic necrosis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, and septic

tenosynovitis.

|

|

|

|

|

Felon Note the area of purulence at the center of

the palmar pad in this thumb with a felon. There is also swelling and

erythema. (Courtesy of Daniel L. Savitt, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Hematoma following traumatic

injury, paronychia, and herpetic whitlow should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Several incision and drainage

techniques are employed in the treatment of a felon, and there is

controversy surrounding which technique is the best to use. Incision and

drainage utilizing a midlateral approach along the nondominant side of

the finger or over the area of greatest fluctuance is commonly used to

drain a felon. An alternative technique is to make a longitudinal volar

incision directly through the finger pad into the pulp space and pus

collection. To ensure complete drainage of the abscess cavity, all

compartments should be entered. The packing of the abscess space is made

with a small, loose-fitting wick to facilitate drainage. Oral antibiotics

directed against gram-positive organisms should be used for 10 days and

the packing removed or replaced after 24 to 48 h.

Clinical Pearls

1. Do not extend the incision

proximal to the distal flexion crease.

2. Incisions should be made

dorsal to the neurovascular bundle; the pincer surfaces (radial aspects

of the index and long fingers and ulnar aspect of the thumb and small

finger) should be avoided when possible.

3. "Hockey stick" and

"fish mouth" incisions are associated with increased occurrence

of unnecessary sequelae and are not recommended.

4. If there is radiographic

evidence of osteomyelitis, bone debridement as well as antibiotic

coverage is required.

|

|

Dry Gangrene

Associated Clinical Features

Gangrene denotes tissue

that has lost its blood supply and is undergoing necrosis. The term dry

gangrene (Figs. 12.3, 12.4) is used for tissues undergoing sterile

ischemic coagulative necrosis, whereas wet gangrene is associated

with bacteria proteolytic decomposition. Streptococcus pyogenes is

often implicated in rapidly developing (6 h to 2 days) gangrene in

traumatic and surgical wounds. Clostridia, anaerobic streptococci, and

mixed aerobic and anaerobic flora can also be seen in wounds caused by

trauma, surgery, or diabetic ulcers.

|

|

|

|

|

Dry

Gangrene Dry gangrene of the

toes showing the areas of total tissue death, appearing as black and

lighter shades of discoloration of the skin demarcating areas of

impending gangrene. (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dry

Gangrene Dry gangrene of the

toes as a result of vascular disease. (Courtesy of Selim Suner, MD,

MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Gas gangrene, frostbite,

cyanosis, traumatic ecchymosis, deep venous thrombosis (DVT), and

subungual hematoma are some conditions that should be included in the

differential diagnosis of gangrene.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The treatment consists of

amputation, debridement, and antibiotic therapy as needed. Underlying

vascular pathology must be evaluated by arteriography and corrected

surgically. Hospitalization is usually required; patients who present

with systemic toxicity may require resuscitation in the ED.

Clinical Pearls

1. Obtain radiographs to help

rule out clostridial myonecrosis and osteomyelitis.

2. Soft-tissue infection may

complicate this condition.

|

|

Gas Gangrene (Myonecrosis)

Associated Clinical Features

Also called clostridial

myonecrosis, this infection causes rapid necrosis and liquefaction of

fascia, muscle, and tendon. The vast majority of cases involve Clostridium

perfringens, which produces a lethal necrotizing hemolytic alpha

exotoxin. Myonecrosis is classically associated with trauma and diabetes.

The inoculation of bacteria occurs either directly into the wound or by

hematogenous spread. There is edematous bronze or purple discoloration,

flaccid bullae with watery brown nonpurulent fluid (Fig. 12.5), and a

foul odor. The most important clinical presentation is pain due to edema

and the rapid production of gas in the infected tissue (Fig. 12.6). Pain

out of proportion to the appearance of the injury is classic. Low-grade

fever, which is an unreliable index of the severity of the infection, and

tachycardia out of proportion to the fever are often present.

|

|

|

|

|

Gas

Gangrene A gangrenous foot

with large bullae, areas of skin that are sloughing, and necrotic

skin. There is also significant swelling. (Courtesy of Selim Suner,

MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gas

Gangrene Lateral view

radiograph of the foot seen in Fig. 12.5. In addition to the

swelling, there is air within the soft tissues, best seen in the

plantar portion of the foot. (Courtesy of Selim Suner, MD, MS.)

|

|

Crepitance and appearance of

gross pockets of air in the tissue may be appreciated but may not be

present early in the course of the illness. The incubation period for

clostridia ranges between 1 and 4 days, but it can be as early as 6 h.

Decreased tissue oxygen tension along with wound contamination are

required for the infection to progress. Factors favoring decreased tissue

oxygen tension include decreased blood supply, foreign body, tissue

necrosis, or wound bacteria, which consume oxygen.

Differential Diagnosis

Crepitant cellulitis, synergistic

necrotizing cellulitis, acute streptococcal hemolytic gangrene, and

streptococcal myositis are some conditions that may be mistaken for

clostridial myositis. Aspiration and Gram's stain showing gram-positive

rods and few leukocytes may help, but often surgical exploration of the

fascia and muscle is required to make the correct diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Aggressive resuscitation with

intravenous fluids is initiated, and consideration is given to packed red

blood cell transfusion. Broad-spectrum antibiotics in conjunction with

penicillin G, in the non-penicillin-allergic patient, is given in the ED.

Tetanus prophylaxis must not be overlooked. Surgical debridement or

amputation, the mainstays of therapy, must be initiated promptly.

Hyperbaric oxygen, in conjunction with surgical and antibiotic therapy,

has been suggested to have a synergistic effect in preventing the

progression of infection and production of toxin.

Clinical Pearls

1. Clostridial infection should

be considered in patients presenting with low-grade fever, tachycardia

out of proportion to the fever, and pain out of proportion to physical

findings.

2. Mortality is 80 to 90% if

untreated, 10 to 25% when treated appropriately.

3. Mixed gram-negative rods and

enterococci are found in nonclostridial gas gangrene, which is

exclusively seen in diabetics and carries a mortality of only 4% when

treated.

4. Gram's stain yielding

gram-positive bacilli with a relative lack of leukocytes can rapidly

confirm clinically suspected clostridial myonecrosis.

|

|

Necrotizing Fasciitis

Associated Clinical Features

This uncommon, severe infection

involves the subcutaneous soft tissues, including the superficial and

deep fascial layers, with early sparing of the skin and late involvement

of the muscle. It is most commonly seen in the lower extremities,

abdominal wall, perianal and groin area, and postoperative wounds but can

manifest in any body part. The infection is spread most commonly from a

site of trauma or surgical wound, abscess, decubitus ulcer, or intestinal

perforation. Alcohol, parenteral drug abuse, and diabetes mellitus are

predisposing factors. Omphalitis may progress to necrotizing fasciitis in

the newborn. Pain, tenderness, erythema, swelling, warmth, shiny skin,

lymphangitis, and lymphadenitis are early clinical findings. Later, there

is rapid progression with changes in skin color, formation of bullae with

clear pink or purple fluid (Fig. 12.7), and cutaneous necrosis (Fig.

12.8), within 48 h. The skin becomes anesthetic and subcutaneous gas may

be present. Systemic toxicity may be manifest by fever, dehydration,

leukocytosis, and frequently positive blood cultures. Fournier's gangrene

is a form of necrotizing fasciitis occurring in the groin and genitalia

(see Figs. 8.9, 8.10). It is rapidly progressive and is associated with a

high mortality rate, particularly in diabetics. The infection can pass

through Buck's fascia of the penis, dartos fascia of the scrotum and

penis, Colles' fascia of the perineum, and Scarpa's fascia of the

abdominal wall. Two groups of organisms are implicated in necrotizing

fasciitis. Type I includes anaerobic species (Bacteroides and Peptostreptococcus)

and type II group A streptococci alone or with Staphylococcus aureus.

|

|

|

|

|

Necrotizing

Fasciitis Large cutaneous

bullae are seen on the leg of this patient with necrotizing

fasciitis. Note the dark purple fluid in the bullae. (Courtesy of

Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Necrotizing

Fasciitis Necrotizing

fasciitis with cutaneous necrosis can be seen in the inner thigh of

this patient. (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Cellulitis, osteomyelitis, gas

gangrene, streptococcal myonecrosis, infected vascular gangrene, and

trauma should all be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Prompt diagnosis is critical in

the treatment of this condition. If the diagnosis is made within 4 days

from the onset of symptoms, the mortality rate is reduced from 50 to 12%.

The initial treatment involves resuscitation with volume expansion. One

recommended initial antibiotic regimen includes a combination of

ampicillin, gentamicin, and clindamycin. Prompt surgical excision is

essential.

Clinical Pearls

1. Intravenous calcium

replacement may be necessary to reverse hypocalcemia from subcutaneous

fat necrosis.

2. Radiographs may be used to

detect subcutaneous gas that is not palpable.

3. Hemolysis and disseminated

intravascular coagulation (DIC) may be seen in association with

necrotizing fasciitis.

4. Necrotizing fasciitis does

not involve muscle, whereas gas gangrene has extensive muscle

involvement.

|

|

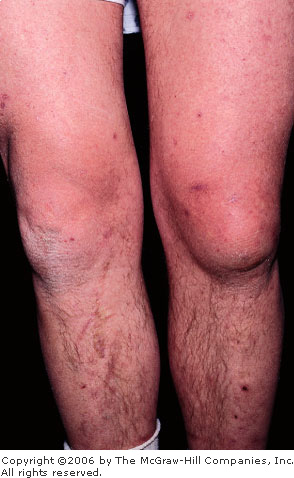

Crystal-Induced Synovitis (Gout and Pseudogout)

Associated Clinical Features

Gout is an inflammatory disease

characterized by deposition of sodium urate monohydrate crystals in

cartilage, subchondral bone, and periarticular structures. Gout is most

frequently associated with inborn errors of metabolism,

myeloproliferative disorders, leukemia, hemolytic anemia, glycogen

storage disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, heavy alcohol

consumption, and worsening renal function (gouty nephropathy). An acute

attack is characterized by sudden onset of monarticular arthritis, most

commonly in the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint of the great toe (named

after the bad-tempered virgin foot goddess "Podagra") (Fig.

12.9). While the great toe MTP is the most common site, gout can occur in

other joints (Figs. 12.10, 12.11). The deposits of crystals in the

tissues about the joint in gout produce a chronic inflammatory response

termed a tophus. Swelling, erythema, and tenderness are common.

|

|

|

|

|

Podagra Podagra denotes gouty inflammation of the

first MTP joint. Note the swelling and erythema of the left first

MTP. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gout Large tophi of gout located in and around the

right knee. (Courtesy of Daniel L. Savitt, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gout The finger is an unusual site for gouty

arthritis. Examination of the synovial fluid confirmed the diagnosis.

(Courtesy of Alan B. Storrow, MD.)

|

|

In pseudogout, calcium

pyrophosphate dihydrate (rod- or rhombus-shaped, weakly birefringent)

crystals are deposited. Pseudogout is most frequently seen in association

with hyperparathyroidism, hemochromatosis, hypophosphatasia,

hypomagnesemia, myxedematous hypothyroidism, and ochronosis. Although any

joint may be involved, knees and wrists are the most common sites. After

joint deposition, the crystals are phagocytized by leukocytes that

release proteolytic enzymes. The acute presenting signs and symptoms are

identical with those of gout, but formation of tophi is not seen with

pseudogout. Fever, pain, and erythema are common to both entities.

Differential Diagnosis

Cellulitis and septic arthritis

must be excluded. In the cell count of the synovial fluid obtained from

an inflamed joint, 2,000 to 50,000 WBCs with polymophonuclear neutrophil

leukocyte (PMN) predominance is expected. Rheumatoid arthritis,

sarcoidosis, hyperparathyroidism, cellulitis, septic arthritis, and

traumatic injury may present much like crystalline-induced synovitis. The

diagnosis is made by seeing negatively birefringent urate crystals or rod

(or rhombus)-shaped, weakly birefringent calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate

crystals on polarized microscopy (see Figs. 21.6A, 21.6B, and 21.6C) with

negative Gram's stain and cultures. Punched out lesions on subchondral

bone may be seen on radiography in chronic tophaceous gout.

Chondrocalcinosis may be seen in pseudogout.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

medications are used with excellent results in the acute setting (e.g.,

indomethacin, 50 mg PO tid if renal function is normal), along with joint

immobilization and rest. Colchicine is a reasonable alternative, but it

often has side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. It is also

associated with serious toxicity, including bone marrow suppression,

neuropathy, myopathy, and death (particularly when given intravenously).

Intramuscular injection of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH, 40 to 80 U

IM or SC) or steroids may be used in patients with contraindications to

colchicine and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Intraarticular

injection of steroids will alleviate symptoms rapidly without systemic

side effects. Allopurinol or probenecid are used in the chronic

management of gout and play no role in acute treatment.

Clinical Pearls

1. Most (90%) of patients with

crystalline-induced synovitis are male and older than 40 years.

2. Serum urate may be elevated

or normal during acute episode.

3. Polyarticular presentation

becomes increasingly more common with long-standing disease.

4. Acute gouty arthritis

attacks may be triggered by minor trauma, diuretic or salicylate use,

alcohol abuse, or dietary indiscretion.

|

|

Ingrown Toenail (Onychocryptosis)

Associated Clinical Features

This painful condition is the

result of impingement and puncture of the medial or lateral nail fold

epithelium by the nail plate. Tenderness and swelling of the nail fold is

followed by granulation tissue growth causing sharp pain, erythema, and

further swelling (Fig. 12.12). If not promptly treated, the granulation

tissue becomes epithelialized, preventing elevation of the nail above the

medial or lateral nail groove. Often there is secondary bacterial or

fungal infection.

|

|

|

|

|

Ingrown

Toenail An ingrown toenail on

the medial aspect of the left great toe. (Courtesy of Frank Birinyi,

MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Paronychia, felon, and benign or

malignant mass should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an

ingrown toenail.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Early: Elevation of the

nail out of nail fold and placement of gauze under nail to prevent

contact, in conjunction with warm soaks, is the initial mode of therapy. Late:

Surgical management involves removal of part of the nail and the inflamed

tissue and sometimes destruction of the involved nail matrix. In the ED,

the lateral portion of the affected nail is removed after digital block

followed by packing of the paronychial fold with petroleum gauze or other

nonadherent dressing. Dressing changes should be done daily, with

follow-up by a podiatrist until growth of the nail plate is complete. The

destruction of the nail matrix is required only in patients with

recurrent infected ingrown toenails and is not part of ED routine

management.

Clinical Pearls

1. Ingrown toenail is most

common in the great toe, is associated with tight-fitting footwear, and

may result from improper nail trimming (i.e., cutting the nail too

short).

2. Antibiotics are indicated

only if cellulitis is suspected, the patient is diabetic, or there is

significant peripheral vascular disease.

3. Use of antibiotics is not a

substitute for surgical excision and will result in only transient

improvement of symptoms.

|

|

Lymphangitis

Associated Clinical Features

Inflammation of lymphatic

channels in the subcutaneous tissues is commonly caused by the spread of

local bacterial infection. Group A streptococcus is the most frequently

implicated agent. Lymphangitis is characterized by red linear streaks

(Figs. 12.13 and 12.14) extending from the site of infection (e.g.,

finger, toe) to regional lymph nodes (e.g., axilla, groin). The lymph

nodes are often enlarged and tender. There may be associated peripheral

edema of the involved extremity. Lymphangitis may develop within 24 to 48

h of the initial infection.

|

|

|

|

|

Lymphangitis Severe lymphangitis is seen in the lower

extremity. The red streak extends from the ankle to the groin and

follows lymphatic channels. In this case, the site of infection was

the great toe. (Courtesy of Liudvikas Jagminas, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lymphangitis The lymphangitis extends from the wrist to the

upper arm. Lymphangitis in the upper extremity commonly arises from

nail biting. (Courtesy of Daniel L. Savitt, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Cellulitis, trauma, and

superficial thrombophlebitis are in the differential diagnosis of

lymphangitis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Rest, elevation, and

immobilization in addition to antibiotics are the mainstays of treatment.

Lymphangitis may be treated with oral antibiotics in afebrile patients

who are not immunocompromised. Coverage for Streptococcus and Staphylococcus

is appropriate. Toxic-appearing patients require admission for parenteral

antibiotics. Any patient sent home with oral antibiotics should be

followed up in 24 to 48 h. Patients who subsequently do not show

improvement require admission for parenteral antibiotic therapy.

Clinical Pearls

1. Consider Pasteurella

multocida with cat bites, Spirillum minus with rat bites, and Mycobacterium

marinum in association with swimming pools and aquaria.

2. Chronic lymphangitis may be

associated with mycotic, mycobacterial, and filarial infection.

3. In Africa and Southeast

Asia, filariasis (Wuchereria bancrofti) is the most common

etiologic agent.

|

|

Lymphedema

Associated Clinical Features

Lymphedema occurs from

obstruction of lymphatic channels and is associated with malignancy,

radiation, trauma, surgery, inflammation, infection, parasitic invasion,

paralysis, renal insufficiency, congestive heart failure, cirrhosis, and

malnutrition. Lymphedema is characterized by painless pitting edema (Fig.

12.15), fatigue, increase in limb size—particularly during the day,

and presence of lymph vesicles. The skin becomes thickened and brown in

the late stages.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pitting

Edema Pitting edema is seen in

a woman with lymphedema of the lower extremities. Note how the

impression of the thumb remains on the foot. (Courtesy of Selim

Suner, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Cellulitis, deep venous

thrombosis (DVT), lymphangitis, traumatic hematoma, right heart failure,

tuberculosis, and lymphogranuloma venereum should be considered when the

diagnosis of lymphedema is made. Subcutaneous dye injection, radiographic

lymphography, and radionuclide lymph clearance may be used to aid in the

diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Control of edema with elevation,

pneumatic compression boots and firm elastic stockings, maintenance of

healthy skin, and avoidance of cellulitis and lymphangitis are the

mainstays of symptomatic treatment. Treatment of the underlying disease

may be curative.

Clinical Pearls

1. Swelling usually starts

distally and progresses proximally.

2. The dorsum of the toes and

feet is always involved in lymphedema, unlike other causes of edema.

3. Careful examination for

right heart failure and screening for renal insufficiency should be

completed for all patients with lymphedema.

|

|

Olecranon and Prepatellar Bursitis

Associated Clinical Features

Bursitis is a reaction in a

fluid-filled synovial sac, commonly over the subacromial (Fig. 12.16),

prepatellar (Fig. 12.17), olecranon, or hip trochanteric bursa. It is

associated with repetitive motion, trauma, or infection. The fluid

collection may be bacterial (septic bursitis, Fig. 12.18), gouty, or,

most commonly, inflammatory. Bursitis is characterized by pain,

tenderness, and swelling. There may be erythema, warmth, and limited

range of motion. It is critical to differentiate septic from benign

inflammation as well as bursal from intraarticular involvement.

Typically, intraarticular arthritis is associated with pain on minor

range of motion, while bursitis discomfort occurs with the stretching of

the skin and synovial sac at the more extreme ranges of joint movement.

The prepatellar bursa is anterior to the infrapatellar tendon. Bursitis

in this area is often the result of repetitive kneeling

("housemaid's knee").

|

|

|

|

|

Olecranon

Bursitis Olecranon bursitis is

evident in this flexed elbow. (Courtesy of Selim Suner, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prepatellar

Bursitis Local bursal swelling

is evident over the left knee. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Septic

Prepatellar Bursitis This

patient presented with obvious purulence of his right prepatellar

bursal sac. Aspiration confirmed septic bursitis. (Courtesy of Alan

B. Storrow, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Septic arthritis, crystal

synovitis, fracture, contusion, and traumatic effusion may mimic this

condition. Since bursitis does not involve the intraarticular space,

signs and symptoms should be isolated to the bursal area. When this

differentiation is difficult by history and examination, fluid aspiration

and analysis of the bursa or joint for cell count, Gram stain, protein,

glucose, and polarized microscopy (see "Crystal-Induced

Synovitis," above) may be helpful. Fluid with > 50,000 cells per

cubic millimeter, polymorphonuclear neutrophil predominance, increased

protein, reduced glucose, and a positive Gram's stain are associated with

bacterial infection.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Rest, bulky compression

dressings, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications are used for

inflammatory bursitis. Bursal injection of local anesthetics (e.g., 2 to

3 mL of lidocaine or bupivacaine) mixed with corticosteroids (e.g., 1 mL

of betamethasone or methylprednisolone) can also be considered. Reducing

the volume of the inflammatory effusion by aspiration may provide

temporary relief, although the effusion has a propensity to recur. Septic

bursitis requires aspiration, gram-positive antibiotic coverage, and

consideration of open incision and drainage. Most patients can be treated

as outpatients with close follow-up.

In contrast, an intraarticular

infection requires aspiration, antibiotics, and admission for

consideration of open drainage. Aspiration and blood cultures prior to

antibiotic administration are helpful to guide therapy toward specific

organisms. Inflammatory arthritis may be treated with anti-inflammatories,

and intraarticular anesthetics and steroids may be considered.

Clinical Pearls

1. The most important

diagnostic issue is differentiation between bursitis and a septic joint.

2. Septic joint infections in

patients with cancer, who are taking corticosteroids, or who are

intravenous drug users may have lower synovial fluid leukocyte counts

(< 30,000/mm3) then usual (> 50,000/mm3).

3. Incision and drainage are

not recommended for routine inflammatory bursitis.

|

|

Palmar Space Infection

Associated Clinical Features

Palmar space infections occur

within the deep soft-tissue planes of the hand and involve the midpalmar

space, the web spaces (collar button abscess), and the thenar (Fig.

12.19) or hypothenar spaces. These infections commonly arise from callus,

fissures, puncture wounds to the palm, and rupture of flexor

tenosynovitis of the digits. The palm loses its concavity, and there is

dorsal swelling. In addition, tenderness, erythema, warmth, and

fluctuance are evident in the palm. A thenar space infection is

characterized by swelling over the thenar eminence and pain with

abduction of the thumb. With a midpalmar space infection, motion

is limited and painful for the middle and ring fingers. Hypothenar

space infections are extremely rare. A high morbidity is associated

with these infections.

|

|

|

|

|

Palmar

Space Infection Thenar space

infection following injury to the thumb. In this palmar view,

erythema and swelling in the right thenar area and abduction of the

thumb are evident. (Courtesy of Richard Zienowicz, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Cellulitis, local traumatic

injury, fractures, and soft tissue mass are included in the differential

diagnosis of palmar space infections.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

All deep space infections of the

hand should be managed by a hand surgeon. Prompt incision and drainage in

the operating room is necessary for the best outcome. Frequently, both

palmar and dorsal incisions are necessary. Loose packing and antibiotic

treatment follow surgery. Parenteral antibiotics against Staphylococcus

aureus as well as anaerobes should be started in the ED.

Clinical Pearls

1. Palmar space infections may

cause swelling on the dorsal hand.

2. In general, erythema,

fluctuance, or tenderness are seen on the palmar aspect with very little

seen dorsally.

|

|

Tenosynovitis

Associated Clinical Features

Tenosynovitis, an inflammation of

the tendon and the surrounding synovial sheath, is characterized by pain

and tenderness. Pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis is infection of the tendon

sheath from hematogenous origin, puncture wounds, or local extension.

Tenosynovitis is characterized by the four signs of Kanavel (described

for a finger flexor tendon): mild flexion contracture; fusiform swelling

along the volar finger surface; tenderness along the entire tendon

sheath, especially at the palmar surface of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP)

joint; and severe pain with passive extension (Fig. 12.20). Tenosynovitis

may be complicated by fibrosis and adhesions leading to stiffness, loss

of function, and tendon necrosis from destruction of the blood supply.

|

|

|

|

|

Tenosynovitis This patient presented with flexor

tenosynovitis of the index finger after a laceration at the level of

the palmar DIP joint. Note the fusiform swelling and redness

extending to the thenar eminence. (Courtesy of Selim Suner, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Cellulitis, traumatic injury,

lymphangitis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, carpometacarpal arthritis,

and allergic reactions may mimic some of the signs and symptoms of

tenosynovitis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

It is difficult to distinguish

infectious and noninfectious etiologies early in the course of this

illness. Early (24 to 48 h) management of tenosynovitis thought to be

noninfectious is accomplished with immobilization and nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory medications. Parenteral antibiotics, rest,

immobilization, elevation, compressive dressing, and early consultation

with a hand surgeon for incision and drainage within 24 to 48 h are

mandated with pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis.

Clinical Pearls

1. Staphylococcus aureus

is the most common organism, but Streptococcus as well as

gram-negative and anaerobic organisms may also be responsible.

2. The most specific sign of

tenosynovitis is pain with passive extension of the digit.

3. The abductor pollicis longus

(APL), the extensor pollicis brevis (EPB), and the wrist are the most

common sites for tenosynovitis.

4. Finkelstein's test is used

to support the diagnosis of de Quervain's tenosynovitis (Fig. 12.21). The

patient is instructed to make a fist with the thumb tucked inside the

other fingers. The wrist is passively deviated to the ulnar side. Sharp

pain along the APL and EPB tendons denotes a positive Finkelstein's test

and is strong evidence of de Quervain's tenosynovitis.

|

|

|

|

|

Finkelstein's

Test Pain over the radial

styloid is elicited with ulnar deviation of the wrist as shown.

|

|

|

|

Thrombophlebitis

Associated Clinical Features

Thrombophlebitis is superficial

thrombosis and inflammation of veins or varicosities characterized by

redness, tenderness, and palpable, indurated, cordlike venous segments

(Fig. 12.22). Common causes of thrombophlebitis are intravenous catheter

insertion, irritant solutions through the intravenous line, and trauma.

There is little risk of embolism when this condition is associated with

varicose veins or superficial veins distal to the popliteal fossa;

however, pulmonary embolism can occur secondary to propagation of the

thrombus of more proximal veins into the deep venous system.

|

|

|

|

|

Thrombophlebitis This photograph shows thrombophlebitis of the

superficial veins in the leg. The thrombosed veins are erythematous,

close to the surface, and palpable. (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack,

MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Septic superficial

thrombophlebitis (Fig. 12.23), lymphangitis, deep venous thrombosis

(DVT), and cellulitis should be included in the differential diagnosis of

thrombophlebitis. The patient must be evaluated for the possibility of

deep venous thrombosis if no underlying cause of superficial thrombosis

is elucidated.

|

|

|

|

|

Septic

Thrombophlebitis

Thrombophlebitis may be complicated by bacterial infection. Note the

purulence associated with the erythematous thrombosed veins.

(Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Elevation with warm compresses,

rest, and analgesia is sufficient treatment for uncomplicated superficial

thrombophlebitis. Superficial thrombophlebitis and involvement of the

saphenofemoral or iliofemoral system requires admission to the hospital

with anticoagulation and treatment as a DVT. Also, admission to the

hospital is warranted if there is extensive involvement, septic signs,

progression of symptoms despite treatment, or severe inflammatory

reactions.

Clinical Pearls

1. Thrombophlebitis of the

greater saphenous vein may be confused with lymphangitis, since the

lymphatic drainage from the leg runs along the vein.

2. This condition is frequently

associated with malignancy—an association known as Trousseau's

syndrome.

3. Since lymphatic drainage

follows the greater saphenous vein, Doppler studies or venography may be

needed to distinguish superficial thrombophlebitis from lymphangitis in

this area.

|

|

Paronychia

Associated Clinical Features

Paronychia is the most common

infection seen in the hand and is characterized by infection and pus

accumulation along a lateral nail fold. Paronychia may spread to involve

the eponychium (Fig. 12.24) at the base of the nail and the opposite nail

fold if untreated. Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequently

implicated organism.

|

|

|

|

|

Paronychia A paronychia involving one lateral fold and

the eponychium. There is swelling, erythema, and tenderness on the dorsum

of the distal phalanx. (Courtesy of Frank Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Felon, dactylitis, herpetic

whitlow, hydrofluoric acid burn, and traumatic injury should be

considered in making the diagnosis of paronychia.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

If paronychia is recognized

early, warm soaks with or without oral antibiotics may be sufficient.

After 2 to 3 days, there may be sufficient pus accumulation along the

eponychial fold to warrant incision and drainage. After digital block, a

longitudinal incision is made along the eponychial fold. If the affected

portion begins under the nail, removal of the proximal nail may be

necessary. Another technique is elevation of the infected eponychium and

lateral nail fold with a number 11 scalpel blade. Incisions should be

packed open with gauze (removed in 24 to 48 h). Oral antibiotics should

be prescribed, and the finger should be reevaluated in 2 to 3 days.

Clinical Pearls

1. Paronychia is typically

associated with nail biting, manicure trauma, and small foreign bodies.

2. Superinfection with fungal

agents may occur with immunocompromised patients or neglected paronychia.

3. Damage to the germinal

matrix during excision of the nail plate results in nail deformity.

4. It is important to distinguish

a paronychia from herpetic whitlow, where incision and drainage is

contraindicated.

|

|

Hypersensitivity Vasculitis

Associated Clinical Features

This patient presented with

discrete palpable purpuric lesions with central necrosis (Fig. 12.25)

surrounded by a rim of erythema. Biopsies of the lesions demonstrated

leukocytoclastic vasculitis consistent with hypersensitivity vasculitis.

|

|

|

|

|

Hypersensitivity

Vasculitis The palpable

purpura of a patient with hypersensitivity vasculitis secondary to

new use of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication. (Courtesy of

Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

The eruption typically begins in

or is limited to the lower extremities. The palpable, nonblanching

purpura or petechiae are usually secondary to a primary vasculitis or an

embolic event which activates complement proteins. These proteins cause

small blood vessel wall segmental inflammation, necrosis, and fibrin

deposition, much as in Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). Features typical

of this problem include self-limited palpable purpura, adult age, equal

sexual incidence, and lack of other examination or laboratory

abnormalities. There may be systemic involvement of the muscles, joints,

GI tract, or kidney as well as pruritus and pain. The duration can be

acute (especially drug-induced), subacute, or chronic.

Hypersensitivity vasculitis is

more likely if the patient has recently received a new drug, or one known

to cause purpura (Fig. 12.25). It can also be caused by sensitivity to

infectious antigens. The cause is idiopathic in approximately 40 to 60%

of patients.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential of purpura must

include infections (bacterial and viral), hematologic abnormalities

(e.g., thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, idiopathic thrombocytopenic

purpura, disseminated intravascular coagulation), collagen-vascular

diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis,

Sjögren's syndrome), and neoplasm. The primary vasculitides—such as

HSP, polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener's granulomatosis, and temporal

arteritis—must also be considered.

The diagnostic criteria for

hypersensitivity vasculitis includes at least three of the following: age

>16 years, related medication, palpable purpura, maculopapular rash,

and appropriate biopsy.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Since the differentiation of

hypersensitivity vasculitis with a vasculitis of bacterial origin is

often difficult, initial antibiotic therapy, blood cultures, and

admission are usually indicated. Multiple episodes, especially if

idiopathic, can occur. The suspected medication should be discontinued

immediately, and the use of steroids can be considered. Other treatment

modalities include the use of immunosuppressive medications and

plasmapheresis.

Clinical Pearls

1. Diagnosis of the primary

vasculitides is almost always made histopathologically.

2. There may be overlap between

the causes of purpura.

3. Self-limited or irreversible

damage may occur to the kidneys.

4. Synonyms for this entity

include necrotizing vasculitis and allergic vasculitis.

|

|

Subclavian Vein Thrombosis

Associated Clinical Features

Thrombosis of the subclavian vein

(Paget–Von Schroetter syndrome) is an uncommon condition usually of

iatrogenic origin. It may also be seen in young patients following

exercise and results from compression injury to the subclavian or

axillary vein from a narrow thoracic outlet (effort thrombosis). Symptoms

of pain, discomfort, and tightness or swelling in the arm are manifest

within a day of the thrombosis (Fig. 12.26). Pitting edema develops in

the fingers, hand, and forearm. There is no arterial insufficiency, and

the pulses are palpable. There is a 15% risk of developing pulmonary

embolism from thrombosis of veins in the upper extremity; however, large

or fatal emboli from this source are very rare. Ascending venography is

the gold standard for diagnosis. Duplex scan, impedance plethysmography, and

Doppler studies are also used, but their accuracy has not been studied in

the upper extremity.

|

|

|

|

|

Subclavian

Vein Thrombosis Left

subclavian vein thrombosis is manifest in this patient by swelling of

the left upper extremity. (Courtesy of Frank Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Superior vena cava syndrome,

trauma to the upper extremity, congestive heart failure, angioedema, and

lymphatic obstruction must be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment consists of elevation,

local heat, analgesia, and anticoagulation with intravenous heparin for

patients presenting with long-term thrombosis. Patients should be

admitted to the hospital. In cases of acute thrombosis (within 5 days of

symptom onset), the treatment is thrombolysis with direct catheter

infusion of urokinase or streptokinase. Surgical thrombectomy has also

been employed. Operative correction of anatomic abnormalities should be

accomplished to prevent long-term morbidity.

Clinical Pearls

1. Swelling of the neck and

face signifies thrombosis of the superior vena cava.

2. The superficial veins in the

upper extremity are often distended and do not collapse when the arm is

elevated.

3. There is a greater incidence

of subclavian vein thrombosis in men and in the right arm.

4. There may be late sequelae

related to the thrombus, such as pain, recurrent swelling, and early

fatigue of the upper extremity.

5. Balloon angioplasty has been

used to correct stenosis of the subclavian vein.

|

|

Cervical Radiculopathy

Associated Clinical Features

Cervical radiculopathy is often

caused by compression of a nerve root by a laterally bulging or herniated

intervertebral disk. Osteoarthritis and spondylosis may also cause

radiculopathy in the cervical spine. Pain results from injury to the

nerve roots and nerves innervating the dura, ligaments, facet joints, and

bone. Common clinical features associated with cervical radiculopathy

include pain, paresthesia, and root signs (sensory loss, lower motor

neuron muscle weakness, impaired reflexes, and trophic changes). The pain

is sharp and stabbing and worse with cough, and it radiates over the

shoulder down the arm. There is often numbness and tingling following a

dermatomal distribution. Root signs may be found corresponding to

anatomic distribution of nerves (e.g., triceps muscle weakness, pinprick

deficit along the middle finger, and atrophy with loss of triceps jerk

associated with C-7 radiculopathy). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and

computed tomography (CT) myelography are the commonly used modalities to

distinguish cervical radiculopathy from disk and bone disease. Electromyelography

studies may also be helpful in ruling out other disease processes.

Differential Diagnosis

Trauma, myelopathy, plexopathy,

neurofibromatosis, metastatic tumor infiltration of nerve roots,

neoplasm, shingles, and central cord syndrome should be considered in the

differential diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The mainstay of ED treatment is

pain control and referral to an orthopedic surgeon or neurosurgeon. Since

prolonged nerve root compression can lead to permanent neurologic

deficits, immediate referral is necessary for progressive neurologic

signs. Patients with intractable pain, progressive weakness in the upper

extremities, and myelopathy should be admitted to the hospital.

Clinical Pearls

1. Most radiculopathies

resulting from cervical disk disease is seen in the 30 to 60 year age

group and in the C-5 to C-7 region.

2. Risk factors for cervical

radiculopathy include heavy lifting, cigarette smoking, frequent diving

from a board, and prior trauma to the neck.

3. Patients with acute cervical

radiculopathy may present with their upper extremity supported by their

head to counteract the cervical root distraction caused by the weight of

their dependent extremity (Fig. 12.27).

|

|

|

|

|

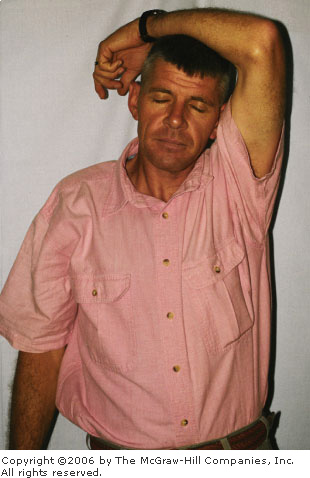

Cervical

Radiculopathy This is the

classic position of relief for cervical radicular pain. This patient

presented with severe pain in the neck with radiation to the

extremity. The only way the patient was able to get relief was by

holding his arm over his head in the position shown. This patient has

a C5–C6 herniated nucleus pulposus. (Courtesy of Kevin J.

Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

Digital Clubbing

Associated Clinical Features

Digital clubbing results from

increased soft tissue density at the tips of the fingers, particularly on

the dorsum. Associated with the increased tissue mass is enhanced blood

flow, excessive curvature of the fingernails, and hyperemic and swollen

skin folds around the fingernail (Fig. 12.28). Clubbing may also be seen

in the toes. The mechanism underlying clubbing is not known, but it is

postulated that the end result is dilatation of the distal digital blood

vessels with soft tissue hypertrophy. Clubbing may be hereditary,

idiopathic, or acquired and is associated with multiple medical

conditions including carcinoma, intrathoracic sepsis, bacterial

endocarditis, cyanotic congenital heart disease, esophageal disorders,

cirrhosis, inflammatory bowel disease, pulmonary disorders, atrial

myxoma, repeated pregnancies, and pachydermoperiostosis. The incidence of

clubbing with each of these conditions is variable. Digital clubbing may

be reversible in certain disease processes.

|

|

|

|

|

Clubbing Marked digital clubbing can be seen in this

patient. Note the hyperemia in the skin folds around the nail.

(Courtesy of Alan B. Storrow, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy,

infection, and trauma should be considered in the differential diagnosis

of clubbing.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment of the underlying

condition is indicated. The disposition depends on the underlying

diagnosis and condition of the patient.

Clinical Pearls

1. Bone radiographs can be used

to diagnose hypertrophic osteoarthropathy. Subperiosteal formation of

bone is seen in the distal diaphyses of long bones.

2. Patients rarely recognize

clubbing in their own fingers even if the condition is marked.

|

|

Phlegmasia Dolens

Associated Clinical Features

Phlegmasia alba dolens (painful

white leg, or milk leg) is caused by extensive thrombosis of the

iliofemoral veins and characterized by pitting edema of the entire lower

extremity, tenderness in the inguinal area, and a pale extremity due to

reflex spasm of the femoral artery. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens (painful

blue leg, Fig. 12.29) arises from thrombosis of the veins in the lower

extremity including the perforating and collateral veins resulting in a

cool, painful, swollen, tense, and cyanotic lower extremity, occasionally

with bullae formation. Compartment syndrome and gangrene may follow.

|

|

|

|

|

Phlegmasia

Dolens Phlegmasia cerulea

dolens of the left lower extremity. Note the bluish discoloration and

swelling. (Courtesy of Daniel L. Savitt, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Arterial insufficiency or

thrombosis, aortic dissection, abdominal aortic aneurysm, deep venous

thrombosis, cellulitis, and lymphedema may mimic these conditions.

Doppler ultrasound, impedance plethysmography, and venography (most

accurate for determining extent) are used in the diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Systemic anticoagulation with

intravenous heparin is indicated for this condition. If there is no improvement

in 12 to 24 h, then iliofemoral venous thrombosis should be suspected.

The role of intravenous thrombolytic therapy is controversial.

Clinical Pearls

1. Pregnancy is one risk factor

for phlegmasia alba dolens.

2. Forty-four percent of

patients with phlegmasia cerulea dolens have an underlying malignancy.

3. Phlegmasia dolens is seen in

fewer than 10% of patients with venous thrombosis.

4. Hypotension may result from

venous pooling of blood in the lower extremity and diminished venous

return to the heart.

5. Petechiae on the skin of the

lower extremity may be present.

|

|

Porphyria Cutanea Tarda

Associated Clinical Features

Porphyrias are problems

associated with enzymatic defects in heme biosynthesis. Porphyria cutanea

tarda (PCT) presents as a condition of fragile skin and vesicles found on

the dorsum of the hands, especially after trauma. The classic symptoms

are easily traumatized skin, leading to blisters in sun-exposed areas,

erosions, milia, and hypertrichosis (Fig. 12.30). It may be induced by

ethanol, estrogens, oral contraceptives, iron overload, and certain

environmental exposures. The typical bullae and erosions may also occur

in other areas, especially the feet and nose. In contrast to other

porphyrias, PCT is not associated with life-threatening respiratory

failure, abdominal pain, or peripheral autonomic neuropathies.

Confirmation of the diagnosis requires 24-h urine testing for various

porphyrins.

|

|

|

|

|

Porphyria

Cutanea Tarda Blisters and

erosions of porphyria cutanea tarda. (Courtesy of Selim Suner, MD,

MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Other forms of porphyria, other

bullous diseases, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), sarcoidosis, and

Sjögren's syndrome must be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Laboratory examination may begin

in the ED with blood chemistries, porphyrin studies, and consideration of

appropriate biopsies. Treatment includes discontinuation of any drugs

that might initiate PCT. Phlebotomy and the use of chloroquine can be

considered.

Clinical Pearls

1. PCT is the most common type

of porphyria.

2. Examination of the urine may

reveal orange-red fluorescence with a Wood's lamp.

3. This condition is sometimes

termed fragile skin.

|

|

Dupuytren's Contracture

Associated Clinical Features

Dupuytren's contracture results

from shortening and fibrotic changes of the subcutaneous tissues of the

palm and longitudinal bands of the palmar aponeurosis. It may begin as a

nodule and then progress to contracture of a finger or fingers (Fig.

12.31). Usually, this is noted at the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint,

but the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) or distal interphalangeal (DIP)

joint, may be involved.

|

|

|

|

|

Dupuytren's

Contracture This chronic

problem is seen at the most common site: the ring finger. (Courtesy

of Alan B. Storrow, MD.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The only effective treatment is

surgery. Recurrence and development of a contracture in other areas may

occur.

Clinical Pearls

1. The flexor tendons are not involved.

2. The ring and small fingers

are the most commonly involved.

|

|

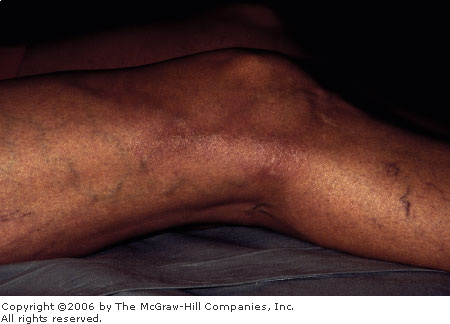

Deep Venous Thrombosis

Associated Clinical Features

Thrombosis in the venous system

results from a disruption of normal hemostasis. As described by Virchow,

blood vessel endothelial injury, coagulopathy, and venous stasis

contribute to formation of clots in the venous system. Deep venous

thrombosis (DVT) is often encountered in patients with intrinsic

coagulopathy or impaired fibrinolysis or those who have had recent

(within 3 months) surgery or trauma. Other associated conditions include

immobilization (e.g., long car or plane trips, bed rest for more than 3

days), increased estrogen (pregnancy, oral contraceptive pills, with

tobacco smoking), cancer, a history of prior DVT, inflammatory disease

processes, or coronary artery disease. Intravenous catheters are also a

major cause of DVT, particularly in the upper extremity.

It is clinically difficult to

tell superficial thrombophlebitis from DVT without diagnostic studies.

Unilateral swelling and tenderness, classically in the calf and thigh,

characterize DVT (Fig. 12.32). Associated erythema, redness and warmth

may lead to a misdiagnosis of cellulitis. Homans' sign—pain

elicited with dorsiflexion of the foot—is not reliable. Even though

venography is considered to be the gold standard test, venous Doppler

ultrasonography is commonly used as the test of choice. Venography is

painful, uses a dye load, and itself may cause DVT. Magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) is highly sensitive and specific but is costly and not

readily available.

|

|

|

|

|

Deep

Venous Thrombosis This patient

has some classic findings of left lower extremity DVT: swelling,

erythema, pain, and tenderness. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Cellulitis is an important

differential diagnosis. Fracture, lymphedema, heart failure, compartment

syndrome, myositis, arthritis, and superficial phlebitis should also be

considered when DVT is diagnosed. A Baker's cyst is a herniation of the

synovial membrane through the posterior knee capsule. While the acute

clinical presentation is swelling behind the knee, rupture of a Baker's

cyst may present with unilateral swelling similar to DVT (Fig. 12.33).

|

|

|

|

|

Ruptured

Baker's Cyst Comparison of

this patient's ankles reveals circumferential swelling around the

right side. MRI revealed a ruptured Baker's cyst in the right

popliteal fossa. Such a presentation may mimic acute lower extremity

DVT. (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Classic treatment of DVT has been

heparin anticoagulation and admission for warfarin loading. With the

development of low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH), one may consider a

subgroup for LMWH administration and outpatient treatment. Careful risk

stratification, preexisting protocols, and close medical follow-up are

necessary for successful outpatient treatment. Thrombolysis should be

reserved for severe cases, where the viability of the extremity is

threatened. Although DVT in the calf and superficial veins of the lower

extremity do not typically embolize, these thrombi can propagate into the

deep venous system and may eventually lead to emboli. Serial diagnostic

studies are performed to follow the course of untreated DVT of the distal

calf.

Clinical Pearls

1. Weight-based heparin is 80

U/kg followed by 18 U/kg/h.

2. Patients with unexplained

DVT should be screened for occult malignancy.

3. Measurement of the calf or

Homans' sign should not be used in isolation to rule out DVT.

4. Patients with an unclear

diagnosis of cellulitis should have an objective study to rule out DVT.

|

|

Arsenic Poisoning

Associated Clinical Features

Inorganic arsenic compounds as

well as sodium and potassium arsenite and arsenate are found in insecticides

and wood preservatives as well as in glass manufacturing. Arsine gas is

produced with metal refining, galvanizing, etching, lead plating, and in

the silicone microchip industry. Acute arsenic poisoning, the most common

cause of acute heavy metal poisoning, is encountered in accidental

ingestion, industrial accidents, suicide, and homicide attempts. Low-dose

exposure in industry or from contaminated water and food products may

lead to chronic poisoning. Arsenic poisoning produces a syndrome involving

the skin, hair, nails, GI system, bone marrow, liver, peripheral and

central nervous systems, and kidneys. Acute symptoms of arsenic poisoning

include violent gastroenteritis, hypotension, prolonged QT interval,

seizures, and coma. Other symptoms such as hair loss (Fig. 12.34),

raindrop hyperpigmentation, characteristic Mees' lines on the nails (Fig.

12.35), anemia and leukopenia, jaundice, subacute sensorimotor

polyneuropathy, paralysis, hematuria, and renal failure are

characteristic of chronic arsenic poisoning. Arsine gas exposure results

in hemolysis and secondary renal failure. Arsenic binds with tissue

sulfhydryl groups, causes direct capillary injury, has direct toxic

effects on large organs, and causes uncoupling of oxidative

phosphorylation.

|

|

|

|

|

Arsenic

Poisoning The patchy hair loss

seen in this photograph is from chronic arsenic poisoning. (Courtesy

of Selim Suner, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Arsenic

Poisoning Characteristic Mees'

lines of chronic arsenic poisoning. Note the transverse white lines

on all the nails of both hands. Mees' lines are often seen in

conjunction with polyneuropathy of arsenic poisoning. (Courtesy of

Robert Hoffman, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Similar symptoms may be seen with

other heavy metal ingestions including thallium toxicity, food-borne

toxins, bacterial diarrhea, renal failure, malaria, psoriasis, and

Hodgkin's disease.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

In the setting of acute arsenic

poisoning, the first priority is to institute advanced life support

measures to stabilize vital signs. Acute ingestion commonly requires

resuscitation with intravenous fluids. Attention is directed to hydration

status, cardiac monitoring, and gathering routine laboratory data.

Standard gastric decontamination techniques, including gastric lavage and

administration of activated charcoal, have been recommended. Although

activated charcoal adsorbs arsenic poorly, it may be effective against

coingestions. Toxicologic consultation should be obtained to determine

the choice of chelating agents, which include dimercaprol (BAL),

dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA), and D-penicillamine.

Hemodialysis is indicated in the setting of renal failure. Diagnosis is

based on clinical findings and 24-h urine arsenic level greater than 100

mg. CBC, liver function tests, electrolytes, BUN, creatinine, and

urinalysis may be helpful in the diagnosis. The level of care is

determined by the presentation, but most patients require admission and

observation for a minimum of 24 h. A 24-h urine collection should be

initiated on all admitted patients.

Clinical Pearls

1. Consider the diagnosis of

acute arsenic poisoning in any patient with unexplained hypotension

accompanied or preceded by severe gastroenteritis.

2. Consider the diagnosis of

chronic arsenic poisoning in any patient with a peripheral neuropathy,

typical skin or hair manifestations, or recurrent gastroenteritis.

3. Remote arsenic exposure can

be elucidated by obtaining levels in scalp and pubic hair.

4. There is a garlic odor on

the breath or skin with arsenic poisoning. 5-Arsenic is absorbed through

the skin, lungs, and GI tract and it crosses the placenta.

|

|