|

Note: Large images and

tables on this page may necessitate printing in landscape mode.

Copyright

©2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved.

Emergency

Medicine Atlas > Part 1. Regional

Anatomy > Chapter 13. Cutaneous Conditions >

|

Erythema Multiforme

Associated Clinical Features

Considered a hypersensitivity

syndrome, erythema multiforme (EM) presents with characteristic target or

iris-shaped papules and vesicobullous plaques (Fig. 13.1). These lesions

are frequently cutaneous manifestations of a drug reaction, viral

infection, Mycoplasma, or malignancy. These plaques are usually

symmetric, pruritic, and painful, often involving the mucous membranes

and extremities, including the palms and soles. The milder form of the

disease has minimal mucosal involvement, no bullae, and no systemic

symptoms. Fever, malaise, extensive mucosal involvement, and other

constitutional symptoms are noted in the severe form of EM, known as

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (see next diagnosis).

|

|

|

|

|

Erythema

Multiforme Note the symmetric

distribution of the target macules. (Courtesy of Michael Redman,

PA-C.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

The maculopapular presentation

may be confused with urticaria or fixed drug eruption, whereas the oral

vesicobullous plaques resemble herpetic gingivostomatitis. However, the

cutaneous target lesions and their symmetry are typical of EM.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Elimination of any possible

etiology (idiopathic cause noted approximately 50%) and supportive

measures to allay the burning and itching are basic to treating this

disorder. Milder forms of the disease usually resolve spontaneously

within 2 to 3 weeks. Corticosteroids are reserved for the severest

presentations. EM minor can be treated on an outpatient basis. However, patients

with significant systemic illness and additional eruptions involving the

mucosal surfaces (Stevens-Johnson syndrome) may require admission and

supportive care.

Clinical Pearls

1. Symmetrically distributed

target lesions on the extensor surfaces of the extremities and a lack of

significant systemic manifestations are classified as EM minor.

2. Drug-associated EM usually

begins within 2 to 3 weeks of initiating therapy. Sulfonamides and

penicillins are most often the culprits.

3. Many clinicians treat

idiopathic cases empirically with a trial of acyclovir therapy owing to

the high incidence of subclinical herpes simplex infection as the cause

of the EM.

|

|

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (EM Major)

Associated Clinical Features

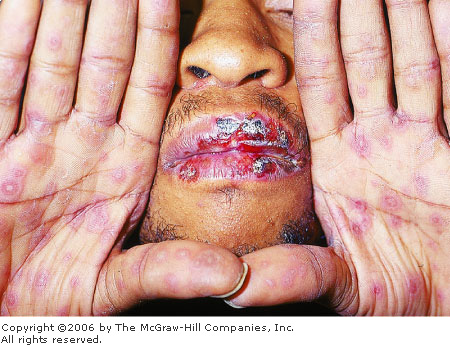

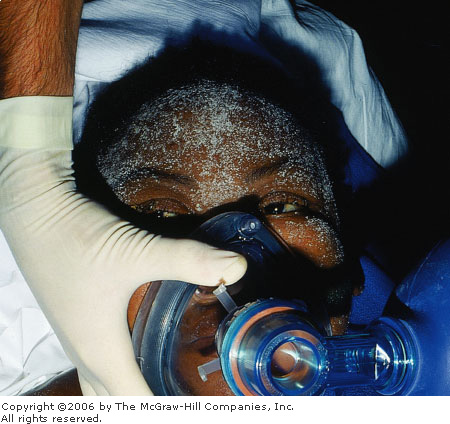

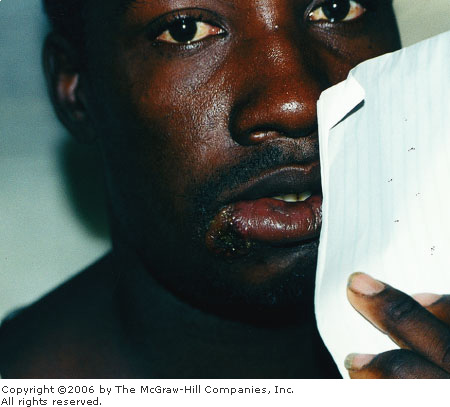

Stevens-Johnson syndrome is a severe,

rarely fatal variety of erythema multiforme. An abrupt onset of

constitutional symptoms precedes the hemorrhagic bullae found on multiple

mucosal surfaces and the edematous, erythematous cutaneous plaques (Fig.

13.2). The bullae erode, producing stomatitis, conjunctivitis,

vulvovaginitis, or balanitis. Patients appear extremely ill and may

develop pneumonia, arthritis, seizures, coma, and hepatic dysfunction.

Death, when it occurs, is usually due to overwhelming sepsis.

|

|

|

|

|

Stevens-Johnson

Syndrome Note the target

lesions on the hands of this patient, as well as the mucosal

involvement on the lips. (Courtesy of Alan B. Storrow, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Meningococcemia must be

considered in the differential diagnosis. The severe involvement of

mucous membranes is characteristic of Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Patients presenting with

significant evidence of toxicity should be admitted to the hospital.

Supportive measures and selective use of systemic corticosteroids are the

cornerstone of therapy.

Clinical Pearls

1. Stevens-Johnson syndrome is

self-limited and usually resolves in approximately 1 month.

2. Sulfonamides, penicillins,

and anticonvulsants are common causes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

|

|

Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Associated Clinical Features

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)

is characterized by the formation of erythematous (scalded) skin followed

by widespread bullae (Fig. 13.3), usually a cutaneous manifestation of a

drug reaction. The epidermis eventually becomes necrotic, leading to

extensive exfoliation and exposure of the raw dermis (Fig. 13.4). A prodrome

of fever, fatigue, myalgias, and skin tenderness occurs in the majority

of patients. The mortality rate approaches 25%, with death usually due to

sepsis or gram-negative pneumonia. TEN is generally considered to be the

most severe form of erythema multiforme.

|

|

|

|

|

Toxic

Epidermal Necrolysis Note the

widespread erythematous bullae and epidermal exfoliation. (Courtesy

of James J. Nordlund, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Toxic

Epidermal Necrolysis The

initial bullae have coalesced, leading to extensive exfoliation of

the epidermis. (Courtesy of Keith Batts, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Early in its course, TEN may

resemble scarlet fever, toxic shock syndrome, or erythema multiforme. In

children, staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome closely mimics TEN;

however, it involves only the superficial epidermis without extension to

the dermis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Supportive care includes

debridement of necrotic tissue, pain control, aggressive hydration,

appropriate antibiotic therapy, and covering exposed dermis, even with

cadaver allografts, to avoid infection and reduce pain. These patients

are best managed in burn treatment centers.

Clinical Pearls

1. Slight pressure causing the

skin to slide laterally and separate from the dermis is a positive

Nikolsky's sign.

2. The initial bullae coalesce,

leading to exfoliation of the entire epidermis.

|

|

Necrotizing (Leukocytoclastic) Vasculitis

Associated Clinical Features

Necrotizing vasculitis is a

hypersensitivity vasculitis in adults associated with infectious agents,

connective tissue diseases, malignancy, and drugs. Symptoms may be

confined to the skin in the form of symmetric petechiae and palpable

purpura over the distal third of the extremities. Systemic vascular

involvement occurs in the kidneys (glomerulonephritis), muscles, joints,

gastrointestinal tract (abdominal pain and bleeding), and peripheral

nerves (neuritis). Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) (Fig. 13.5) is the

classic example of vasculitis in children, consisting of a clinical triad

of palpable purpura, arthritis, and abdominal pain. It is usually a

benign, self-limited disease that occurs in children most commonly after

a bacterial or viral infection.

|

|

|

|

|

Henoch-Schönlein

Purpura Note the classic acral

distribution of HSP. It is immunoglobulin A (IgA)–mediated and

most commonly occurs in children after a streptococcal or viral infection.

(Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic

purpura (ITP), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC),

meningococcemia, gonococcemia, Rocky Mountain spotted fever,

staphylococcal septicemia, and embolic endocarditis must all be

considered in the differential diagnosis; however, patients with septic

vasculitis are generally more severely ill, with rapidly progressive

symptoms. Also, the purpura of septic vasculitis tend to be fewer in

number, asymmetric, and distal in location. Biopsy of the purpura is

helpful in distinguishing necrotizing vasculitis from septic vasculitis,

DIC, and embolic endocarditis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

A majority of cases are

self-limited and require only rest, elevation, and analgesics. Severe

cases with systemic manifestations may require admission for supportive

care, corticosteroids, and cytotoxic immunosuppressive therapy.

Antibiotics should be utilized if the vasculitis follows an infection.

Clinical Pearls

1. The petechiae and purpura of

necrotizing vasculitis are usually localized to the lower third of the

extremities.

2. A patient presenting with

purpura and the signs and symptoms of serum sickness should lead the

examiner to consider necrotizing vasculitis.

|

|

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

Associated Clinical Features

Rickettsia rickettsii is

transmitted by the bite of an infected tick. Fever, rigors, headache,

myalgias, and weakness occur 7 to 10 days after inoculation. The

initially blanching macular eruption begins at approximately 4 days on

the distal extremities and somewhat later on the palms and soles (Fig.

13.6). It soon becomes petechial as it spreads centrally to involve the

trunk and abdomen. However, it can also present without obvious cutaneous

manifestations.

|

|

|

|

|

Rocky

Mountain Spotted Fever These

erythematous macular lesions will evolve into a petechial rash that

will spread centrally. (Courtesy of Daniel Noltkamper, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Viral exanthems, drug eruptions,

necrotizing vasculitis, purpuric bacteremia, and meningococcemia may all

resemble this potentially fatal illness.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Doxycycline or chloramphenicol is

required for this potentially fatal illness. Doxycycline is the drug of

choice, yet it should be avoided in pregnant or lactating women and

children younger than 8 years of age. Mildly ill patients may be treated

with oral antibiotics on an outpatient basis as long as close follow-up

can be arranged. More severely ill patients should be admitted because

their care can be complicated by circulatory collapse and coma.

Approximately 20% of untreated patients will die; overall mortality is 3

to 7%.

Clinical Pearls

1. Palmar and plantar petechiae

in a severely ill patient should be treated as Rocky Mountain spotted

fever until proved otherwise.

2. Most cases occur between

April and October, with the highest incidence occurring in the Southeast

and South-Central states.

|

|

Disseminated Gonococcus

Associated Clinical Features

Disseminated gonococcus (GC) is a

systemic infection, with septic vasculitis following the hematogenous

dissemination of the organism Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The spectrum of

disease varies from skin lesions alone to skin lesions with tenosynovitis

or septic arthritis. The initial lesion is an erythematous macule that

evolves into a necrotic, purpuric vesicopustule (Fig. 13.7). These

purpura are few in number, asymmetric, and predominantly distal in

location.

|

|

|

|

|

Disseminated

Gonococcus A classic

presentation of the asymmetric purpuric rash, vesicopustule, and

polyarthritis in the hands of an individual with disseminated GC.

(Courtesy of Glaxo Wellcome Pharmaceuticals.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

The purpura may resemble

meningococcemia, staphylococcal septicemia, necrotizing vasculitis, or

endocarditis with emboli. Infectious arthritis or tenosynovitis must be

considered when the patient presents with joint complaints. It is

important to obtain Gram's stain of the contents of the vesicopustule, as

well as all other body sites and fluids.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Therapy consists of intravenous

or intramuscular ceftriaxone or cefotaxime until symptoms either improve

or resolve, followed by an additional 7 days of orally administered

ciprofloxacin or cefuroxime. Hospitalization is recommended for

noncompliant patients or cases noted to have an associated septic

arthritis.

Clinical Pearls

1. The most common symptom of

disseminated GC is arthralgia of one or more joints, primarily involving

the hands or knees.

2. Skin lesions develop in up

to 70% of cases and will resolve within 4 days regardless of antibiotics.

3. Less than one-third of

patients will have urethritis.

4. The purpura of septic

vasculitis (of whatever bacterial etiology) tend to be fewer in number,

asymmetric, and distal in location.

|

|

Infective Endocarditis

Associated Clinical Features

Infective endocarditis is an

illness characterized by fever, valve destruction, and peripheral

embolization manifested by rare, usually distal purpura. Streptococcus

viridans is the most common causative organism. Janeway lesions (Fig.

13.8) occur in 5% of cases and consist of nontender, small, erythematous

macules on the palms or soles. Osler's nodes (Fig. 13.9) occur in 10% of

cases and consist of transient, tender, purplish nodules on the pulp of

the fingers and toes. Splinter hemorrhages are black, linear

discolorations beneath the nail plate (Fig. 13.10). They are present in

20% of cases and are more suggestive of subacute bacterial endocarditis

(SBE) if present at the proximal or middle nail plate. Murmurs, retinal

hemorrhages, septic arthritis, and significant embolic episodes such as

pulmonary embolism or stroke may also be present.

|

|

|

|

|

Janeway

Lesions Peripheral

embolization to the sole, resulting in a cluster of erythematous

macules known as Janeway lesions. (Courtesy of the Department of

Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical

Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Osler's

Nodes Subcutaneous, purplish,

tender nodules in the pulp of the fingers known as Osler's nodes.

(Courtesy of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Bethesda, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Splinter

Hemorrhages Note the splinter

hemorrhages along the distal aspect of the nail plate, due to emboli

from subacute bacterial endocarditis. (Courtesy of the Armed Forces

Institute of Pathology, Bethesda, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Meningococcemia, gonococcemia,

staphylococcal septicemia, and necrotizing vasculitis must all be

considered in the differential diagnosis. Echocardiography can aid in the

diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Antibiotics must be appropriate

for the infectious agent; however, therapy is often required before the

diagnosis is confirmed or the infecting organism is known. All toxic

patients require admission, as do all febrile patients who have

prosthetic valves or who are intravenous drug abusers. These patients

should receive gentamicin with nafcillin or vancomycin empirically

pending the blood culture results. Patients with rheumatic or congenital

valve abnormalities may receive streptomycin with penicillin or

vancomycin.

Clinical Pearls

1. Janeway lesions, Osler's

nodes, and splinter hemorrhages in a febrile patient with a murmur are

virtually diagnostic of infective endocarditis.

2. Rheumatic heart disease is

the most common predisposing factor, with the mitral valve being the most

common site of damage.

3. Congenital heart disease,

intravenous drug abuse, and prosthetic heart valves are additional

predisposing factors to the development of infective endocarditis.

|

|

Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura

Associated Clinical Features

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic

purpura (ITP) occurs as the result of platelet injury and destruction.

Pinpoint, red, nonblanching petechiae or nonpalpable purpura and

ecchymoses are found on the skin (Fig. 13.11) and mucous membranes,

either spontaneously (platelets <10,000/mm3) or at the site

of minimal trauma (platelets <40,000/mm3). Melena,

hematochezia, menorrhagia, and severe intracranial hemorrhages may also

occur in conjunction with the purpura. The acute form affects children 1

to 2 weeks after a viral illness; the chronic form occurs most often in

adults, with women outnumbering men 3:1, and may present with an

associated splenomegaly.

|

|

|

|

|

Idiopathic

Thrombocytopenic Purpura This

thrombocytopenic patient with splenomegaly has pinpoint,

nonblanching, nonpalpable petechiae. (Courtesy of the Department of

Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical

Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Nonhemorrhagic vascular

dilatations like telangiectasia or true petechiae and purpura, as found

in scurvy or posttraumatic purpura, must be differentiated from this

potentially debilitating illness. Assessment of the platelet count aids

in making the diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Hospitalization at the time of

diagnosis is recommended because the differential diagnosis is extensive

and the bleeding risks are significant. Platelets are transfused only if

there is life-threatening bleeding or the total count is <10,000/mm3.

Immunosuppressive drugs, steroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin are of

benefit in the acute cases; splenectomy is utilized in chronic cases.

Clinical Pearls

1. Petechiae and purpura in a

thrombocytopenic patient with splenomegaly make the diagnosis.

2. The acute form of ITP has an

excellent prognosis (90% spontaneous remission), whereas the course of

chronic ITP is one of varying severity with little hope of remission.

|

|

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP)

Associated Clinical Features

The diagnosis of thrombotic

thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is characterized by the following pentad

of symptoms:

1. Microangiopathic hemolytic

anemia, with characteristic schistocytes on the peripheral blood smear

and a reticulocytosis.

2. Thrombocytopenia with

platelet counts ranging from 5000 to 100,000/ L (Fig.

13.12). L (Fig.

13.12).

3. Renal abnormalities

including renal insufficiency, azotemia, proteinuria, or hematuria.

4. Fever.

5. Neurologic abnormalities

including headache, confusion, cranial nerve palsies, seizures, or coma.

|

|

|

|

|

Thrombic

Thrombocytopenic Purpura

Bleeding at initial presentation is seen in about 30 to 40% of

patients with TTP. (Courtesy of James J. Nordlund, MD.)

|

|

The disease affects women more

than men and can affect any age group, but it occurs most commonly in

ages 10 to 60.

Differential Diagnosis

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS),

disseminated intravascular coagulation, and the pregnancy-associated

HELLP (Hemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes, Low Platelet count) syndrome

can all present like TTP. HUS and TTP appear to be closely related and

may represent variants of a single disease.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The cornerstone of therapy is

plasma exchange transfusion. Some patients can be treated with plasma

infusions alone. It is thought that the transfusions provide a missing

substrate and the exchange may remove some unknown toxic substance.

Prednisone and antiplatelet therapy with aspirin may be helpful. Patients

recalcitrant to standard therapy may be treated with immunosuppressives

(vincristine, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide) and even splenectomy. All

patients should be admitted.

Clinical Pearls

1. Platelet transfusions should

be avoided unless there is life-threatening hemorrhage; they can worsen

the thrombotic process.

2. Typically TTP is acute and

fulminant, but it can become a chronic, relapsing form.

3. Hemoglobin less than 6 g/dL,

platelet count less than 20,000, elevated indirect bilirubin and LDH, and

a negative Coombs test are typically found.

|

|

Livedo Reticularis

Associated Clinical Features

Livedo reticularis presents as a

macular, reticulated (lace-like) patch of nonpalpable cutaneous vasodilatation

(Fig. 13.13) in response to a variety of vascular occlusive processes.

This pattern predominates in the peripheral or acral areas and may or may

not be associated with purpura. In time, the overlying epidermis and

dermis may infarct and form ulcerations or develop palpable dermal

papules or nodules. Livedo reticularis is usually representative of a

severe underlying systemic disease. Inflammatory vascular diseases

(livedo vasculitis, polyarteritis nodosa, lupus erythematosus), septic

emboli (meningococcemia), tumors (pheochromocytoma), and systemic

illnesses associated with mechanical vessel blockage (anticardiolipin

antibody syndrome, polycythemia vera, sickle cell anemia, cholesterol

embolus) are a few diseases associated with or responsible for livedo

reticularis. It can also occur independent of any disease association.

|

|

|

|

|

Livedo

Reticularis Note the

reticulated (lace-like) blanching erythema symmetrically distributed

over the lower extremities. (Courtesy of James J. Nordlund, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

The most important consideration

in making this diagnosis is to rule out an associated vascular occlusion

of whatever etiology.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The treatment of livedo

reticularis is treatment of the underlying disorder and avoiding exposure

to cold.

Clinical Pearls

1. Livedo vasculitis is an

inflammatory vascular disease usually found symmetrically on the ankles

and dorsum of the feet. It consists of painful stellate-shaped

ulcerations surrounded by an erythematous livedo pattern.

2. Cholesterol emboli usually

occur after an intraarterial procedure. Pain often precedes the livedo

pattern of purpura on the distal extremities.

3. Patients with

anticardiolipin antibody syndrome have extensive livedo reticularis and

recurrent arterial and venous thromboses involving multiple organ

systems.

|

|

Herpes Zoster

Associated Clinical Features

Herpes zoster is a dermatomal,

unilateral reactivation of the varicella zoster virus. Pain, tenderness,

and dysesthesias may present 4 to 5 days prior to an eruption composed of

umbilicated, grouped vesicles on an erythematous, edematous base (Fig.

13.14). The vesicles may become purulent or hemorrhagic. Nerve

involvement may actually occur without cutaneous involvement. Ophthalmic

zoster involves the nasociliary branch of the fifth cranial nerve and

presents with vesicles on the nose and cornea (Hutchinson's sign).

Ramsay-Hunt syndrome is a herpes zoster infection of the geniculate

ganglion that presents with decreased hearing, facial palsy, and vesicles

on the tympanic membrane, pinna, and ear canal.

|

|

|

|

|

Herpes

Zoster This eruption consists

of a dermatomal distribution of umbilicated vesicles on an

erythematous base. Note the occasional cluster of hemorrhagic

vesicles. Tzank smear is positive. (Courtesy of the Department of

Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical

Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

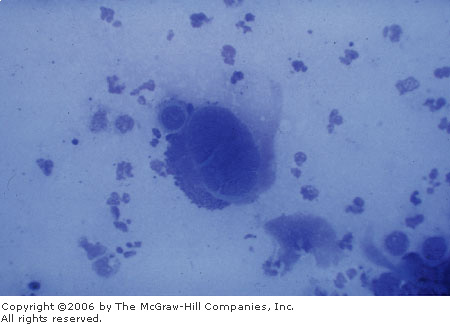

Differential Diagnosis

The most likely differential

diagnosis is herpes simplex infection, which is usually recurrent. Herpes

zoster recurs in fewer than 5% of immunocompetent patients. The eruption

may resemble contact dermatitis, localized cellulitis, or grouped insect

bites. The prodromal pain must be differentiated from potential pleural,

cardiac, or abdominal origin. Tzank smear of the floor of a vesicle

demonstrating multinucleated giant cells makes the diagnosis of a herpes

family infection (Fig. 13.15). Cultures may be necessary to distinguish

herpes zoster forms.

|

|

|

|

|

Herpes

Zoster A Tzank smear of both

the roof and floor of a herpetic vesicle demonstrating a

multinucleated giant cell. (Courtesy of the Department of

Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical

Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Uncomplicated cases of herpes

zoster can be managed with supportive care, especially pain control.

Admission to the hospital for intravenous acyclovir is usually reserved

for complicated cases involving multiple dermatomal distribution or the

ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve, disseminated disease, or

immunocompromised patients. Acyclovir or famciclovir hasten the healing

and decreases the pain if started within 72 h of appearance of the

vesicles. These agents have also been shown to reduce the duration of

postherpetic neuralgia. Prednisone may also prove useful. Herpes zoster

keratitis requires immediate ophthalmologic consultation to avoid any

potential vision loss.

Clinical Pearls

1. Dermatomally grouped,

umbilicated vesicles on an erythematous base are diagnostic of herpes

zoster.

2. The thorax is the most

common area involved, followed by the face (trigeminal nerve).

3. The nonimmune or

immunocompromised should avoid lesional contact from prodrome until

reepithelialization, since the crusts can contain the varicella zoster

virus.

4. Typically, an infected

patient may transmit chickenpox to a nonimmune individual.

5. Zoster during pregnancy

seems to have no deleterious effects on the mother or baby.

|

|

Herpetic Whitlow

Associated Clinical Features

Herpetic whitlow is a painful

herpes simplex infection of the distal finger characterized by edema,

erythema, vesicles, and/or pustules grouped on an erythematous base (Fig.

13.16). Fever, lymphangitis, and regional adenopathy often accompany the

lesion.

|

|

|

|

|

Herpetic

Whitlow Note the cluster of

vesicles on an erythematous base located at the distal finger. Tzank

smear is positive. (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Paronychia, felon, and contact

dermatitis must be differentiated from this contagious illness. A Tzank

smear of the floor of the vesicle demonstrating multinucleated giant

cells makes the diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Acyclovir in addition to

analgesics and antipyretics are useful. To be most effective, acyclovir

must be started within 72 h of the appearance of the eruption. Topical

antibiotic ointments help prevent secondary infection and may speed

healing.

Clinical Pearls

1. Grouped, umbilicated

vesicles on an erythematous base are diagnostic of a herpes family

infection.

2. Wear protective gloves;

herpetic whitlow is an occupational hazard in the medical and dental

professions.

|

|

Erysipelas

Associated Clinical Features

Erysipelas is a group A

streptococcal cellulitis involving the skin to the level of the dermis.

The plaque is typically erythematous, edematous, and painful, with an

elevated, well-demarcated border (Fig. 13.17). The associated edema tends

to make the plaque appear shiny. Erysipelas frequently occurs on the face

and lower extremities.

|

|

|

|

|

Erysipelas Note the well-demarcated, edematous,

erythematous, shiny plaque. (Courtesy of the Department of

Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical

Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Other significant

illnesses—such as deep venous thrombosis, thrombophlebitis, and

necrotizing fasciitis—must be ruled out.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

All infections require rest,

elevation, heat, and antibiotics. Mild presentations may be treated on an

outpatient basis with oral dicloxacillin or erythromycin in

penicillin-allergic patients. More severe illness or toxicity requires

hospitalization and intravenous antibiotics.

Clinical Pearls

1. The well-demarcated, tender,

shiny, erythematous plaque is diagnostic of erysipelas.

2. This same shiny, erythematous

plaque on the face of a febrile child may be caused by Haemophilus

influenzae, necessitating intravenous chloramphenicol or a

cephalosporin.

3. Lymphatic streaking is more

common in erysipelas than cellulitis.

|

|

Hot Tub Folliculitis

Associated Clinical Features

Hot tub folliculitis is a

pruritic, follicular, pustular eruption confined to the hair follicle and

is secondary to a cutaneous infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa

(Fig. 13.18). Headache, sore throat, earache, and fever may accompany the

pustules, which usually localize to the trunk and proximal extremities.

|

|

|

|

|

Hot

Tub Folliculitis Note the

pustules localized to the hair follicles of the trunk and proximal

extremity. (Courtesy of Jeffrey S. Gibson, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Other forms of folliculitis

(including those caused by Staphylococcus aureus), acne, and

miliaria rubra are usually considered in the differential diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The folliculitis usually

involutes in 7 to 10 days without treatment. Acetic acid compresses and

local wound cleansing may speed recovery. In addition, the hot tub or

source of exposure must be decontaminated to avoid reexposure.

Clinical Pearls

1. Pruritic pustules confined

to the hair follicles of the trunk and proximal extremities is diagnostic

of folliculitis.

2. This most commonly occurs in

individuals who use hot tubs, whirlpools, or saunas.

3. This may also result from

contact with chemicals (exfoliative beauty aids) or repetitive physical

trauma (friction from tight clothing).

|

|

Ecthyma Gangrenosum

Associated Clinical Features

Ecthyma gangrenosum is a Pseudomonas

aeruginosa infection that usually occurs in the septic,

immunocompromised, or neutropenic patient. The initially erythematous

macules develop bullae or pustules (Fig. 13.19) surrounded by violaceous

halos. The pustules become hemorrhagic and rupture, forming painless

ulcers with necrotic, black centers.

|

|

|

|

|

Ecthyma

Gangrenosum A typical

hemorrhagic bulla of ecthyma gangrenosum secondary to pseudomonal

sepsis. (Courtesy of James Mensching, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Necrotizing vasculitis, fixed

drug eruptions, pyoderma gangrenosum, and brown recluse spider bites must

all be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

These patients are usually septic

and immunocompromised. Admission is usually required for the patient to

receive antipseudomonal antibiotics and general supportive care.

Clinical Pearls

1. Consider ecthyma gangrenosum

when examining a septic patient who presents with bullae or pustules that

rupture and form painless, necrotic ulcers.

2. It is important to consider

underlying immunodeficiency when making this diagnosis.

|

|

Pityriasis Rosea

Associated Clinical Features

Pityriasis rosea is a mild

inflammatory, exanthematous, papulosquamous eruption. The pathognomonic

finding is an oval salmon-colored papule with a central collarette of

scale. It primarily occurs on the trunk with the long axis of the oval

papule following the lines of cleavage in a Christmas tree–like

distribution (Fig. 13.20). A herald patch, consisting of a much larger

plaque with central clearing and scales, frequently precedes the

exanthematous phase by 1 to 2 weeks (Fig. 13.21). The eruption usually

lasts 4 to 6 weeks and is frequently pruritic.

|

|

|

|

|

Pityriasis

Rosea An exanthematous,

papulosquamous eruption, with the long axis of the oval papules

following the lines of cleavage in a Christmas tree–like

eruption. (Courtesy of James J. Nordlund, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Herald

Patch A herald patch precedes

the exanthematous phase: a larger, oval, salmon-colored patch with a

central collarette of scale. (Courtesy of the Department of

Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical

Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

This must be differentiated from

the secondary lesions of syphilis, tinea versicolor, and some drug

eruptions.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Symptomatic treatment is usually

all that can be offered to the patient. Antihistamines may alleviate the

associated pruritus. Ultraviolet light has also been used with some

success.

Clinical Pearls

1. A salmon-colored papule with

central scale, negative KOH examination for hyphae, and negative

serologic testing for syphilis makes the diagnosis of pityriasis rosea.

2. It frequently appears in

very atypical form in dark-skinned individuals (acral, face, and genital

location).

|

|

Secondary Syphilis

Associated Clinical Features

The initial papules of secondary

syphilis are usually asymptomatic, although they may be painful or

pruritic; they appear 2 to 10 weeks after the primary chancre. Headache,

sore throat, fever, arthralgias, myalgias, and a generalized

lymphadenopathy may also be present. These exanthematous papules are

symmetric and nondestructive, usually forming a pityriasis

rosea–like pattern on the trunk, palms, and soles (Figs. 13.22,

13.23). Later lesions are firm, pigmented papules with a coppery tint and

adherent scales (Fig. 13.24). Macerated papules may form on the mucous

membranes; "motheaten" alopecia may occur on the scalp; and

condylomata lata may occur in the intertriginous areas.

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary

Syphilis These eruptive,

scaly, copper-colored papules on the foot may be the initial

presentation of secondary syphilis. They are usually symmetric,

asymptomatic, and nondestructive. (Courtesy of the Department of

Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical

Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary

Syphilis These firm,

pigmented, erythematous papules are characteristic of secondary

syphilis. (Courtesy of Lynn Utecht, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary

Syphilis These firm, pigmented

papules with a coppery tint and adherent scale are characteristic.

(Courtesy of the Department of Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical

Center and Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Syphilis is "the great

imitator." It may resemble psoriasis, drug eruptions, pityriasis

rosea, viral exanthems, tinea corporis, tinea versicolor, and condyloma

acuminata. A positive serologic test for syphilis makes the diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Penicillin is the agent of choice

for treatment, with tetracycline or erythromycin used in cases of

penicillin allergy. A Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction may occur several hours

after treatment with antibiotics, correlating with the clearance of

spirochetes from the bloodstream. This reaction lasts approximately 24 h,

yet it may be more threatening than the disease itself. Increasing fever,

rigors, myalgias, headache, tachycardia, hypotension, and a drop in the

leukocyte and platelet count may be encountered. Fluid resuscitation to

maintain the blood pressure and supportive care may be needed.

Clinical Pearls

1. Scaly palmar and plantar

papules are strongly suggestive of secondary syphilis, the incidence of

which is rising.

2. These scaling red-brown

papules appear 2 to 10 weeks after the spontaneous resolution of the

initial painless chancre.

3. The latent stage follows the

resolution of the papules; it is characterized by a positive serology and

an absence of signs and symptoms.

4. Tertiary syphilis occurs in

untreated or poorly treated patients and may manifest itself as general

paresis, tabes dorsalis, optic atrophy, and aortitis with aneurysms.

5. It is important to consider

the prozone phenomenon (falsely negative agglutination in undiluted

serum) in an AIDS patient with presumed syphilis in whom the serologic

test is negative.

|

|

Erythema Chronicum Migrans (ECM)

Associated Clinical Features

Borrelia burgdorferi is

the tick-borne spirochete responsible for Lyme borreliosis, and erythema

chronicum migrans (ECM) is the pathognomonic rash of Lyme disease

occuring early in the infection. The initial prodromal symptoms of fever,

myalgias, arthralgias, and headache are followed by a macule or papule

progressing to a plaque at the site of the bite. This plaque expands its

red, raised border as it clears centrally, leading to an annular

appearance (Fig. 13.25). The plaque may burn and is rarely pruritic. On

average, there are 9 days between the time of the bite and the appearance

of the rash.

|

|

|

|

|

Erythema

Chronicum Migrans (ECM) This

pathognomonic eruption of Lyme disease forms at the site of the tick

bite. The initial papule forms into a slowly enlarging oval area of

erythema while clearing centrally. (Courtesy of Timothy Hinman, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

This annular plaque may resemble

a fixed drug eruption, tinea corporis, urticaria, or the herald patch of

pityriasis rosea. The multiple secondary annular papules and plaques that

may rarely form can resemble secondary syphilis. However, the

Lyme-related eruption spares the palms and soles.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The duration of antibiotic

treatment (10 to 30 days) depends on the severity of the symptoms.

Tetracycline or doxycycline are the drugs of choice. Pregnant or

lactating females and children younger than 8 years of age should be

treated with penicillin or amoxicillin. Erythromycin is a suitable

alternative. Patients with minimal symptoms may be treated on an

outpatient basis. Those patients with significant toxicity and

complications require admission, supportive care, and parenteral

antibiotics.

Clinical Pearls

1. An annular plaque arising at

the site of a tick bite in a patient with systemic symptoms should be

treated as Lyme disease until proved otherwise.

2. Stage I of Lyme disease

consists of constitutional symptoms and the characteristic rash of ECM.

3. Stage II of Lyme disease

consists of neurologic (aseptic meningitis, encephalitis, bilateral

Bell's palsy) and cardiac (myocarditis, conduction blocks)

manifestations.

4. Stage III of Lyme disease

consists of an asymmetric, episodic, oligoarticular arthritis.

|

|

Tinea Corporis, Faciale, and Manus

Associated Clinical Features

Tinea corporis includes all

dermatophyte infections excluding the scalp, face, hands, feet, and

groin. The dermatophytosis is pruritic and consists of well circumscribed

scaly plaque with a slightly elevated border and central clearing (Fig.

13.26). This annular configuration is most commonly found on the trunk

and neck. Skin scrapings viewed with a KOH preparation exhibit septate

hyphae.

|

|

|

|

|

Tinea

Corporis This dermatophytosis

is known as ringworm, a well-defined, pruritic, scaly plaque with a

raised border and central clearing (annular). KOH preparation is

positive. (Courtesy of the Department of Dermatology, Wilford Hall

USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

Tinea faciale is a dermatophyte infection of the

facial skin. It commonly appears as a well circumscribed erythematous

patch (Fig. 13.27). Tinea manus is a dermatophyte infection of the hands

(Fig. 13.28).

|

|

|

|

|

Tinea

Faciale Note the sharply

marginated, polycyclic, scaly plaque with central clearing localized

to the face. KOH preparation is positive. (Courtesy of the Department

of Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army

Medical Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tinea

Manus This dermatophytosis is

usually unilateral when it involves the hands. Note the diffuse

hyperkeratosis of the left hand as well as involvement of both feet

(tinea pedis). (Courtesy of James J. Nordlund, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Pityriasis rosea, secondary

syphilis, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and tinea versicolor are all

usually considered in the differential diagnosis. A KOH examination of

the scale demonstrating hyphae confirms the diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Small, localized plaques may be

treated with a topical antifungal cream. Extensive or resistant infection

requires systemic griseofulvin or ketoconazole. It is important to treat

for 2 weeks beyond the point of clinical cure to ensure successful

eradication of the fungus.

Clinical Pearls

1. The scale is usually located

at the leading edge of erythema and provides the best yield for scraping

as part of the KOH examination.

2. The recurrence rate is high,

especially for tinea manus.

|

|

Tinea Cruris

Associated Clinical Features

Tinea cruris, or "jock itch,"

is a pruritic dermatophytosis of the intertriginous areas, usually

excluding the penis and scrotum. The scaly, erythematous plaque spreads

peripherally, with central clearing (Fig. 13.29). The borders of the

plaque are well defined.

|

|

|

|

|

Tinea

Cruris This dermatophytosis is

commonly called "jock itch." Note the erythematous, scaly

plaque with its well-defined border. It characteristically does not

involve the scrotum or penis. KOH preparation is positive. (Courtesy

of James J. Nordlund, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Erythrasma, Candida albicans,

seborrheic dermatitis, and psoriasis are usually considered in the differential

diagnosis. A KOH examination of the scale demonstrating hyphae confirms

the diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Initial treatment consists of

topical antifungal medications. Griseofulvin or ketoconazole are reserved

for resistant cases. It is important to treat for 1 week beyond the point

of clinical cure to ensure successful eradication of the fungus.

Decreasing the amount of perspiration by using topical powders may help

prevent recurrences.

Clinical Pearls

1. A less well defined,

pruritic, intertriginous plaque that typically involves the scrotum is

usually erythrasma. It is caused by Nocarelia minutissimus and is

treated with topical erythromycin.

2. Warmth and moisture are

predisposing factors.

|

|

Tinea Pedis

Associated Clinical Features

Tinea pedis, or "athlete's

foot," is a pruritic dermatophytosis. It consists of erythema and

scaling of the sole (see Fig. 13.28), maceration, occasional

vesiculation, and fissure formation between and under the toes (Fig.

13.30). These pruritic, painful fissures may become secondarily infected

with gram-negative organisms. Frequently the toenails are also affected.

|

|

|

|

|

Tinea

Pedis A pruritic, scaling

hyperkeratotic rash involving the soles of the feet and extending to

the interdigital spaces is pathognomonic for tinea pedis. (Courtesy

of James J. Nordlund, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Foot eczema, psoriasis, and

Reiter's syndrome are considered in the differential diagnosis. A KOH

examination of the scale demonstrating hyphae confirms the diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Topical antifungal creams are the

initial treatment of choice. Antibiotics may be used to treat secondary

infection. Griseofulvin, then ketoconazole, are used for chronic or

resistant cases. It is important to treat for 1 week beyond the point of

clinical cure to ensure successful eradication of the fungus.

Clinical Pearls

1. If it scales, scrape it and

look for hyphae.

2. Macerated areas may become

secondarily infected by bacteria.

|

|

Tinea Capitis

Associated Clinical Features

Tinea capitis is scalp ringworm,

or a dermatophytosis of the scalp. It presents as a pruritic,

erythematous, scaly plaque with broken or missing hairs frequently

referred to as "gray patch" or "black dot" ringworm

(Fig. 13.31). This may develop into a kerion. A kerion is a delayed-type

hypersensitivity reaction to the fungus, where the initial erythematous,

scaly plaque becomes boggy with inflamed, purulent nodules and plaques

(Fig. 13.32). The hair follicle is frequently destroyed by the

inflammatory process in a kerion, leading to a scarring alopecia.

|

|

|

|

|

Tinea

Capitis This dermatophytosis

is characterized by a pruritic, circular area of hair loss covered by

adherent scales. KOH preparation is positive. (Courtesy of the

Department of Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and

Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kerion This collection of boggy, inflamed, purulent

nodules and papules is the result of a delayed-type hypersensitivity

reaction to the fungus. Scarring alopecia will follow as a result of

the actual destruction of the hair follicle. (Courtesy of the

Department of Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and

Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Various inflammatory follicular

conditions—such as folliculitis, impetigo, psoriasis, alopecia

areata, and seborrheic dermatitis—may resemble tinea capitis. The

diagnosis is made by a KOH examination of a scraping of the area,

revealing hyphae and spores.

Emergency Department Treatment

Disposition

Systemic griseofulvin is usually

required for several weeks to treat tinea capitis successfully. Systemic

antibiotics and corticosteroids are usually added when treating a kerion.

Selenium sulfide lotion used as a shampoo may actually decrease the

duration of the infection. It is important to treat for 2 weeks beyond

the point of clinical cure to ensure successful eradication of the

fungus. Ketoconazole is reserved for resistant cases.

Clinical Pearls

1. Tinea capitis is a disease

of childhood; it is rare in immunocompetent adults.

2. It is epidemic in many

African American communities.

3. The KOH scrape is aided by

using a disposable urethral brush or similar device.

|

|

Onychomycosis

Associated Clinical Features

Onychomycosis is an invasion of

the nails by any fungus. Four clinical subtypes are noted. Distal

subungual presents as discolorations of the free edge of the nail

with hyperkeratosis leading to a subungual accumulation of friable

keratinaceous debris (Fig. 13.33). White superficial consists of

sharply outlined white areas on the nail plate which leave the surface

friable. Proximal subungual presents as discolorations which start

proximally at the nail fold. Candidal onychomycosis encompasses

the entire nail plate, leaving the surface rough and friable.

|

|

|

|

|

Onychomycosis Note that multiple nail beds have been invaded

by the fungus, leading to chronic hyperkeratosis and subungual

accumulation of friable keratinaceous debris. (Courtesy of the

Department of Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and

Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Psoriasis and various other nail

dystrophies, such as distal onycholysis caused by excessive water

exposure or drugs, must be differentiated from this fungal infection.

Pseudomonal nail infection is characterized by the subungual accumulation

of green debris. A KOH examination of the keratinaceous debris

demonstrating hyphae confirms onychomycosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The most common treatment

consists of oral griseofulvin, fluconazole, lucenazole, or terbinafine.

Candidal infections require oral ketoconazole. Toenail onychomycosis is

very difficult to eradicate.

Clinical Pearls

1. All that causes the nail

plate to separate from the nail bed is not necessarily fungus.

2. Distal subungual is the most

common type of onychomycosis.

|

|

Tinea Versicolor

Associated Clinical Features

Tinea versicolor is a chronic,

superficial fungal infection that involves the trunk and extremities with

little or no involvement of the face. The fungus is part of normal skin

flora. Finely scaling brown macules are present in fair-skinned patients

(Fig. 13.34), whereas scaly hypopigmented macules are often noted in the

dark-skinned (Fig. 13.35). These sharply demarcated macules are

intermittently pruritic.

|

|

|

|

|

Tinea

Versicolor This chronic

superficial fungal infection leads to the formation of multiple

well-defined, scaly brown macules on the trunk and extremities.

(Courtesy of the Department of Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical

Center and Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tinea

Versicolor An example of

hypopigmented areas on dark skin. (Courtesy of James J. Nordlund,

MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Pityriasis rosea, secondary

syphilis, and some drug eruptions must all be considered in the

differential diagnosis. A KOH examination of a scraping of the area

revealing hyphae and spores makes the diagnosis (see Fig. 21.16).

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment consists of short

applications of selenium sulfide lotion, topical antifungal creams, or

topical ketoconazole. Resistant cases require oral ketoconazole.

Ultraviolet exposure is required to regain any lost pigment.

Clinical Pearls

1. Tinea versicolor is more

common in adolescents and young adults.

2. Clinically active areas or

areas colonized with the fungus may be identified by orange fluorescence

noted on Wood's light examination.

|

|

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Associated Clinical Features

Basal cell carcinoma is a

malignancy of the basal cell layer of the epidermis, presenting as a

translucent, pearly papule with central ulceration and rolled borders

with fine superficial telangiectasias (Fig. 13.36). It is most frequently

located on the head, neck, and upper trunk. The patient frequently notes

easy bleeding of the papule with poor to nonhealing. There are several

variants of basal cell carcinomas. Pigmented basal cell carcinoma consists

of a brownish-black, firm nodule with irregular surface and central

ulceration (Fig. 13.37). Superficial multicentric basal cell carcinoma is

psoriasiform in nature, consisting of a flat, erythematous, scaly

translucent plaque without central ulceration or raised border (Fig.

13.38).

|

|

|

|

|

Basal

Cell Carcinoma Nodular basal

cell carcinoma consists of a firm, centrally ulcerated (rodent ulcer)

nodule with a raised, rolled, pearly, telangiectatic border.

(Courtesy of the Department of Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical

Center and Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pigmented

Basal Cell Carcinoma This

pigmented basal cell carcinoma consists of a firm, translucent,

brownish-black ulcerated nodule with an irregular surface and

asymmetry of its border. (Courtesy of the Department of Dermatology,

Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical Center, San

Antonio, TX.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Basal

Cell Carcinoma A superficial

multicentric basal cell carcinoma is frequently psoriasiform in

nature. Note the flat, erythematous, scaly plaque with its elevated,

irregular border. (Courtesy of the Department of Dermatology, Wilford

Hall USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio,

TX.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Pigmented basal cell carcinoma

resembles nodular melanoma. Superficial multicentric basal cell carcinoma

resembles psoriasis, tinea corporis, and squamous cell carcinoma in situ.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Excisional surgery, cryosurgery,

or electrosurgery are recommended forms of treatment. If there is a

potential for disfigurement, radiation therapy is usually instituted

instead of surgery. Prompt dermatologic consultation must be arranged

when evaluating any suspicious lesion. Up to half of patients will

develop a recurrence.

Clinical Pearls

1. Basal cell carcinoma is the

most common form of skin cancer.

2. This malignancy forms in the

epidermis that has developing hair follicles; therefore, it is not found

on the vermilion border of the lips or the genital mucosal membranes.

3. The pearly, rolled,

telangiectatic border with central ulceration is diagnostic of basal cell

carcinoma.

4. Despite being locally

invasive, basal cell carcinoma does not metastasize.

|

|

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Associated Clinical Features

Squamous cell carcinoma varies

from erythematous, hyperkeratotic, sharply demarcated plaques to

elevated, ulcerative nodules (Fig. 13.39). It may be sun-induced or

related to ionizing radiation or industrial carcinogens. Invasive

squamous cell carcinoma is characterized by a discrete elevated plaque or

nodule with thick keratotic scale and ulceration.

|

|

|

|

|

Squamous

Cell Carcinoma Note the single

erythematous, scaly plaque on the dorsal aspect of this sun-exposed

hand. (Courtesy of the Department of Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF

Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Squamous cell carcinoma must be

differentiated from a benign lesion such as tinea corporis, psoriasis,

impetigo, wart, seborrheic keratosis, or keratoacanthoma (Fig. 13.40).

|

|

|

|

|

Keratoacanthoma This rapidly evolving neoplasm consists of an

erythematous nodule with a hyperkeratotic core. It most closely

resembles a squamous cell carcinoma although it is a benign

epithelial neoplasm. Biopsy serves to differentiate these two

conditions. (Courtesy of the Department of Dermatology, Wilford Hall

USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Excisional surgery is required,

with radiation therapy utilized in potentially disfiguring cases. All

suspicious lesions require prompt dermatologic consultation.

Clinical Pearls

1. Squamous cell carcinoma is

the second most common type of skin cancer.

2. This malignancy develops

more commonly in fair-skinned people with a significant history of sun

exposure.

3. Most lesions are found on

the lips or other sun-exposed areas.

4. A rapidly evolving (2 to 4

weeks) nodule or plaque with a dense hyperkeratotic core is a

keratoacanthoma. It is closely related to squamous cell carcinoma and frequently

occurs at a site of trauma. Treatment is the same.

5. Risk of metastasis is

related to size, location, and histology.

|

|

Melanoma

Associated Clinical Features

Melanoma is a malignancy

involving the melanocytes of the epidermis. Asymmetry, an irregular

border, a mottled display of color, a diameter greater than 5 to 6 mm,

and an elevation or distortion of the surface are five signs that a

lesion may be a melanoma (Fig. 13.41). Melanoma may or may not occur in

sun-exposed areas.

|

|

|

|

|

Melanoma Note the asymmetry, irregular border, and

focal hyperpigmentation in this melanoma. (Courtesy of the Department

of Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army

Medical Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Lentigo maligna is characterized

by a single, flat, freckle-like macule with an irregular border, usually

on the face (Fig. 13.42). This melanoma in situ is often confused with a

solar lentigo or a seborrheic keratosis and has about a 5% risk of being

malignant. Superficially spreading melanoma is the most common form of

melanoma. It usually presents as a brown macule with irregular borders and

variegation in color. Nodular melanoma usually starts as a papule which

becomes an elevated nodule with irregular borders and variegation in

color (Fig. 13.43). It must be differentiated from a hemangioma,

angiokeratoma, or pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Acral lentiginous

melanomas, which are agressive and metastasize easily, are often mistaken

for plantar warts or subungual hematomas; they are flat, pigmented,

irregularly bordered macules of the palms, soles, and subungual areas

(Fig. 13.44).

|

|

|

|

|

Lentigo

Maligna Melanoma This

long-lived melanoma in situ has now invaded the dermis, forming a

black nodule classified as lentigo maligna melanoma. (Courtesy of the

Department of Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and

Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nodular

Melanoma This melanoma has

progressed to an exophytic tumor, which was deeply invasive

histopathologically. (Courtesy of the Department of Dermatology,

Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical Center, San

Antonio, TX.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Acral

Lentiginous Melanoma The

finding of a pigmented, irregularly bordered macule involving the

proximal nail fold is called Hutchinson's sign. It represents

melanoma of the nail matrix and is therefore classified as an acral

lentiginous melanoma. (Courtesy of the Department of Dermatology,

Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical Center, San

Antonio, TX.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

A melanoma must be surgically

excised with adequate margins. Prompt dermatologic consultation is

required of all suspicious lesions, because the prognosis of melanoma

correlates directly with early detection and treatment.

Clinical Pearls

1. Prognosis of melanoma is

most dependent on the depth of invasion, therefore, early detection and

treatment are essential.

2. Only 20% of melanomas arise

from preexisting moles, so the appearance of a new mole, especially after

the age of 30, is particularly significant.

3. Most benign moles have

symmetry, one color, and are less than 7 mm in diameter.

|

|

Pyogenic Granuloma

Associated Clinical Features

Pyogenic granuloma is

characterized by a solitary, violaceous, pedunculated or sessile vascular

nodule which usually forms at the site of cutaneous injury (Fig. 13.45).

The well demarcated nodule consists of exuberant granulation tissue

("proud flesh") which may be erosive and encrusted. Pyogenic

granuloma commonly occurs on the digits and is particularly common in

pregnancy.

|

|

|

|

|

Pyogenic

Granuloma This solitary,

violaceous, pedunculated, vascular nodule formed at the site of an

injury. Note that the nodule is well demarcated by a thin rim of

epidermis. (Courtesy of the Department of Dermatology, Wilford Hall

USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

This benign vascular neoplasm

resembles a hemangioma; however, it must be differentiated from

amelanotic melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and metastatic renal cell

carcinoma.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Since this neoplasm usually does

not resolve spontaneously, it may be shaved off with electrodessication

of the base.

Clinical Pearls

1. A fine collarette of scale

surrounding an exophytic vascular neoplasm is diagnostic.

2. The lesion may exhibit

recurrent bleeding episodes.

3. Nearly 25 to 33% of these

benign lesions follow some form of minor trauma.

|

|

Fixed Drug Eruption

Associated Clinical Features

A fixed drug eruption is a

cutaneous reaction to an ingested drug, usually an over-the-counter

laxative, barbiturate, tetracycline, or sulfa drug. The reaction occurs

at the identical site with repeated exposure to the same drug, usually on

the genital skin or proximal extremity. It presents as a round, pruritic,

erythematous, sharply demarcated plaque that may evolve into a painful

bulla with secondary erosion (Fig. 13.46). Residual hyperpigmentation

frequently follows healing.

|

|

|

|

|

Fixed

Drug Eruption This red to

violaceous, pruritic, sharply demarcated patch is a cutaneous

reaction to a drug. Repeated exposure will cause a similar reaction

in the same location. (Courtesy of the Department of Dermatology,

Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical Center, San

Antonio, TX.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Early cellulitis, erythema

multiforme, arthropod assault, and genital herpes are usually considered

in the differential diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The etiology must be identified

and removed before the plaque will resolve. Symptomatic treatment

includes antihistamines and analgesics.

Clinical Pearls

1. The identical recurrence of

a painful, pruritic, well-demarcated violaceous plaque makes the

diagnosis.

2. This reaction occurs with

repeated exposure to the same drug.

3. Some patients have a

refractory period following exposure.

|

|

Exanthematous Drug Eruptions

Associated Clinical Features

Exanthematous drug eruptions are

an adverse hypersensitivity reaction to a drug. This symmetric, pruritic,

morbilliform, blanching, erythematous eruption is the most frequent of

cutaneous drug eruptions (Fig. 13.47). The initially pruritic macules or

papules usually become confluent and may progress to an exfoliative

dermatitis.

|

|

|

|

|

Exanthematous

Drug Eruption This symmetric,

morbilliform, blanching eruption may eventually become confluent,

leading to an exfoliative dermatitis. (Courtesy of GlaxoWellcome

Pharmaceuticals.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Viral exanthem, secondary

syphilis, atypical pityriasis rosea, and scarlet fever must all be

considered in the differential diagnosis. A serologic test for syphilis,

antistreptolysin O titer, and a good history are usually sufficient to

make the diagnosis. Severe drug eruptions may be accompanied by

eosinophilia, lymphadenopathy, and liver function abnormalities.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The eruption may resolve despite

the drug's continued use. The drug should be discontinued if considered

to be the cause of the rash. It may take as long as 2 weeks for the eruption

to fade after discontinuation of the causative drug. Symptomatic

management includes antihistamines and topical corticosteroids.

Clinical Pearls

1. Drug eruptions are usually

symmetric and pruritic as opposed to viral eruptions, which are usually

asymmetric and asymptomatic.

2. Mononucleosis patients

taking amoxicillin or AIDS patients taking sulfa drugs frequently

experience this reaction.

|

|

Erythema Nodosum

Associated Clinical Features

Erythema nodosum is a delayed

hypersensitivity reaction, usually to certain drugs, infections, or

systemic illnesses. This panniculitis (inflammation of the fat) consists

of painful, nonulcerated, poorly marginated nodules with overlying

erythematous, warm, shiny skin. (Fig. 13.48). The lower legs are the most

common site; the face is rarely involved. Fever, malaise, and arthralgias

often accompany the cutaneous manifestations.

|

|

|

|

|

Erythema

Nodosum These multiple painful

nodules with overlying erythematous, warm and shiny skin were

associated with coccidioidomycosis and are typical of erythema

nodosum. (Courtesy of GlaxoWellcome Pharmaceuticals.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Erythema induratum, syphilitic

gummas, and nodular vasculitis are considered in the differential

diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Identify and treat the underlying

etiology. Oral contraceptives, sulfa drugs, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, fungal

infections, and inflammatory bowel disease are common predisposing

factors. Symptomatic treatment includes nonsteroidal anti-inflamatory

drugs (NSAIDs), bed rest, and compressive dressings.

Clinical Pearls

1. Erythema nodosum most

commonly presents in young women secondary to oral contraceptives or

sulfa drugs.

2. Its appearance in

association with systemic fungal infections (coccidioidomycosis)

indicates a likely recovery from the disease.

|

|

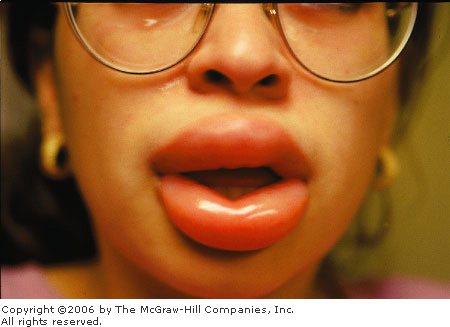

Urticaria and Angioedema

Associated Clinical Features

Urticaria, a vascular reaction

localized to the skin, is composed of transient, erythematous, edematous,

pruritic papules or plaquelike wheals (Figs. 13.49, 13.50). It tends to

favor the covered areas (back, chest, buttocks). Angioedema comprises

thicker plaques that result from fluid shift into the dermis and

subcutaneous tissues. It generally affects the distensible tissues (lips,

eyelids, earlobes, Fig. 13.51) and is usually nonpruritic. There are

countless causes of urticaria; the most common being food, medications,

and underlying infection. Cholinergic urticaria involves micropapular

lesions induced by exercise or heat. Dermatographism presents as linear

hives at the site of skin stroking. Cold urticaria (Fig. 13.52) can be

diagnosed with the ice cube test, and solar urticaria occurs in areas

exposed to sunlight. Urticaria may also occur as a result of exposure to

pressure, heat, and water. Hereditary angioedema is an autosomal dominant

disorder with systemic manifestations secondary to edema of the subcutaneous

and mucosal tissues of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract in

addition to the face and extremities. Mortality rates approach 30%,

usually from airway obstruction. There is also an acquired form of

angioedema secondary to an underlying malignancy, usually

lymphoreticular. The use of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE)

inhibitors is a frequent cause of angioedema.

|

|

|

|

|

Urticaria Note the edematous papules and wheals covering

the skin of the neck. (Courtesy of Alan B. Storrow, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Urticaria Note the classic raised plaques on the lower

extremity of this patient with urticaria. (Courtesy of James J.

Nordlund, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Angioedema Prominent lip involvement in a young woman

with ACE inhibitor–induced angioedema. (Courtesy of Alan B.

Storrow, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cold

Urticaria Plaque formation

after placement of an ice cube on the skin confirms cold urticaria.

(Courtesy of James J. Nordlund, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Bacterial or viral exanthems,

erythema multiforme, and drug eruptions must be considered in the

differential diagnosis of urticaria. Edema of any etiology (congestive

heart failure, glomerulonephritis, chronic liver disease) must be

differentiated from the soft tissue swelling associated with angioedema.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

This involves the identification

and elimination of any potential etiology. Antihistamines can be

effective for urticaria, often requiring both H1 and H2

blockers and steroids for stubborn cases. Life-threatening attacks of

hereditary angioedema do not respond well to antihistamines, epinephrine,

or steroids. Admission for supportive care and active airway management

is the mainstay of treatment. Danazol may be utilized for prophylactic

management.

Clinical Pearls

1. Both urticaria and

angioedema are acute and evanescent.

2. Urticaria is pruritic and

responsive to antihistamines, epinephrine, and steroids.

3. Angioedema is only rarely

pruritic and minimally responsive to epinephrine; it may require danazol

for long-term treatment.

4. Doxepin may be considered

for refractory cases due to its potent H1 and H2

blocking effect.

|

|

Dyshidrotic Eczema (Pompholyx)

Associated Clinical Features

Dyshidrotic eczema is a

papulovesicular plaque involving the epidermis of the fingers, palms, and

soles. The dermatosis initially consists of pruritic, deep-seated

vesicles grouped in clusters (Fig. 13.53). Scaling and painful fissure

formation are late complications, as is secondary bacterial infection.

Spontaneous remissions and recurrent attacks are usually the rule. The

bullous form is called pompholyx.

|

|

|

|

|

Dyshidrotic

Eczema Note the cluster of

deep-seated vesicles along the sides of the fingers. Scaling and

painful fissure formation may also occur. No overlying erythema is

present. (Courtesy of the Department of Dermatology, Wilford Hall

USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Acute contact dermatitis must be

considered in the differential diagnosis of the acute eruption. Psoriasis

and dermatophytosis are considered in the differential diagnosis of the chronic

eruption.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Burow's wet dressings should be

utilized during the early vesicular stage. High-potency topical steroids

are used in all stages of the eruption. Systemic corticosteroids should

be avoided except for the most severe cases. Antihistamines treat the

pruritus. Dicloxacillin or erythromycin are used to treat secondary

bacterial infections. Minimal exposure to water and generous emolliation

also hasten healing.

Clinical Pearls

1. Deep-seated, tapioca-like

vesicles on the sides of the digits, followed by scaling and fissure

formation, are typically seen in this disease.

2. Dyshidrotic eczema is

frequently associated with psychosocial stressors.

3. The "id reaction,"

due to fungal infections and drug eruptions, may have similar clinical

presentations.

|

|

Atopic Dermatitis

Associated Clinical Features

Atopic dermatitis is a broadly

defined pruritic inflammation of the epidermis and dermis, with

approximately 60% of the cases occurring during the first year of life.

The characteristic pattern is erythema, papules, and lichenified plaques

with excoriation and exudation of wet crusts (Fig. 13.54). Its

distribution is the face (sparing of the mouth), the antecubital and

popliteal fossae, and the dorsal surfaces of the forearms, hands, and

feet. This is generally considered a lifelong condition with gradual

improvement toward adulthood.

|

|

|

|

|

Atopic

Dermatitis Lichenfied plaques,

erosions, and fissures are characteristic of atopic dermatitis.

(Courtesy of James J. Nordlund, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Nummular eczema, allergic contact

dermatitis, impetigo, dermatophytosis, and psoriasis are usually

considered in the differential diagnosis. A KOH examination of the scale

rules out dermatophytosis. A biopsy may help differentiate this condition

from nummular eczema and contact dermatitis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Antihistamines treat the

pruritus. Unscented emollients prevent xerosis (dry skin). Topical

corticosteroids treat the underlying inflammation. Systemic

corticosteroids should be avoided except for the most severe cases. Since

these patients are frequently colonized with Staphylococcus aureus,

antistaphylococcal antibiotics are also used during flares of the

condition.

Clinical Pearls

1. Scaly plaques on the

flexural surface with excoriation and exudation of crusts is diagnostic

of atopic dermatitis.

2. Asthma and allergic rhinitis

may develop as the atopic dermatitis improves.

|

|

Nummular Eczema

Associated Clinical Features

Nummular eczema is a pruritic,

eczematous dermatitis consisting of closely grouped vesicles that

coalesce into coin-shaped, erythematous plaques with poorly defined

borders (Fig. 13.55). These plaques may become encrusted or dry and

scaly. They are usually found on the trunk and extremities (especially

the hand) of a middle-aged or elderly patient.

|

|

|

|

|

Nummular

Eczema An example of multiple

erythematous, coin-shaped plaques with fine scales, representative of

this pruritic, eczematous dermatitis. (Courtesy of the Department of

Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical

Center, San Antonio, TX.)

|