|

Note: Large images and

tables on this page may necessitate printing in landscape mode.

Copyright

©2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved.

Emergency

Medicine Atlas > Chapter 14. Pediatric

Conditions > Newborn Conditions >

|

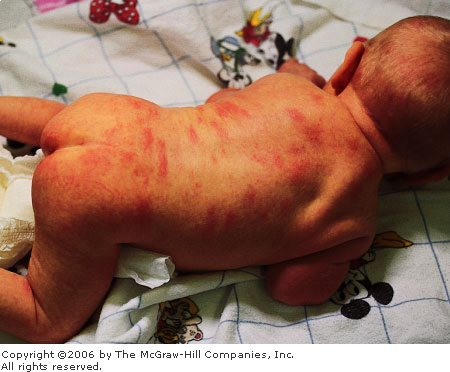

Erythema Toxicum

Associated Clinical Features

This benign, self-limited

eruption of unknown etiology in newborns is characterized by small,

erythematous macules 2 to 3 cm in diameter (Fig. 14.1) with 1- to 3-mm

firm pale yellow or white papules or pustules in the center. This rash

usually presents within the first 2 to 3 days of life. Each individual

lesion usually disappears within 4 or 5 days. New lesions may occur

during the first 2 weeks of life. Wright-stained slide preparations of

the scraping from the center of the lesion demonstrate numerous

eosinophils.

|

|

|

|

|

Erythema

Toxicum Newborn infant with

diffuse macular rash of erythema toxicum. (Courtesy of Kevin J.

Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Transient neonatal pustular

melanosis, newborn milia, miliaria, herpes simplex, and impetigo of the

newborn should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

As this condition is

self-limiting, no therapy is indicated in the setting of a well-appearing

newborn with normal activity and appetite. In cases where impetigo, Candida,

or herpes infections are suspected, a smear from the center of the lesion

and culture may be necessary to make a final diagnosis.

Clinical Pearl

1. Erythema toxicum is the most

common rash of the newborn (up to 50% of full terms). The lesions may be

present anywhere on the body but tend to spare the palms and soles.

|

|

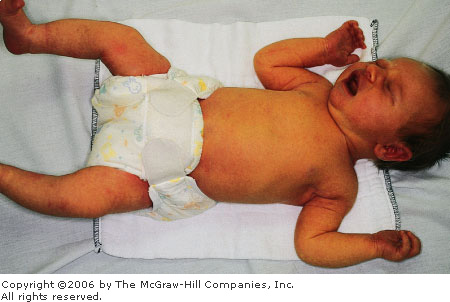

Salmon Patches (Nevus Simplex)

Associated Clinical Features

Nevus simplex (salmon patches) is

the most common vascular lesion in infancy, present in about 40% of

newborns. It is described as a slightly red, flat, macular lesion on the

nape of the neck, the glabella, forehead, or upper eyelids (Figs. 14.2

and 14.3). In general, the eyelid lesions fade within a year and the

glabellar within 5 to 6 years. The lesions on the neck often persist.

|

|

|

|

|

Salmon

Patches Newborn with

characteristic salmon patches over his face. (Courtesy of Anne W.

Lucky, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Salmon

Patches Child with patch over

lower back consistent with salmon patches. (Courtesy of Anne W.

Lucky, MD.

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Nevus flammeus (port-wine stain)

can have a similar appearance.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Parental education and

reassurance can be helpful, but no treatment is indicated.

Clinical Pearls

1. In general, flat, vascular

birthmarks tend to persist through life. Raised vascular birthmarks

usually disappear with time.

2. When this lesion is seen on

the nape of the neck, it is frequently referred to as a stork bite.

|

|

Neonatal Jaundice

Associated Clinical Features

Physiologic jaundice (Fig. 14.4)

is observed in 25 to 50% of term newborns. Most cases are self-limited

and generally without sequelae. The physiologic (<12 mg/dL) jaundice

of the newborn usually peaks between the second and fourth day. In

preterm infants, this peak occurs later. Physiologic jaundice is believed

to be due to a combination of factors including an increase of bilirubin

production following a breakdown of fetal red blood cells associated with

a temporary decrease in conjugation of these by-products by the immature

newborn liver. Risk factors for unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia include

maternal diabetes, prematurity, drugs, polycythemia, traumatic delivery

with cutaneous bruising or hematoma, and breast-feeding. Most infants with

jaundice have no disease, but a careful history and organized approach is

necessary to identify pathologic causes when these patients present to

the ED. Kernicterus is a condition resulting from a severe form of

unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia and is associated with mental

retardation, deafness, seizures, choreoathetosis, and a multitude of

other irreversible neurologic abnormalities.

|

|

|

|

|

Neonatal

Jaundice Newborn with

yellowish hue to skin consistent with jaundice. (Courtesy of Kevin J.

Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Jaundice within the first 24 h of

life is usually associated with sepsis, erythroblastosis fetalis, and

bleeding disorders or hemorrhage (traumatic delivery with cutaneous

bleeding or hematomas). Physiologic jaundice first appears on the second

or third day. Any patient presenting with jaundice after the third day of

life should be carefully evaluated for the possibility of sepsis.

Late-onset jaundice could be suggestive of septicemia, breast milk

jaundice, galactosemia, hemolytic anemias, drug-induced

hyperbilirubinemia, pyloric stenosis or duodenal atresia, Crigler-Najjar

syndrome, or Gilbert's disease.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Initial laboratory workup should

include blood type and Coombs' test, complete blood count with smear for

red cell morphology and reticulocyte count, and indirect and direct

bilirubin. Other studies may be ordered according to the clinical

presentation and history. Initial management should ensure adequate

hydration and treatment of the underlying condition. Acidosis should be

corrected, since bilirubin precipitates in acid media. In cases of physiologic

jaundice, the level of serum bilirubin at which to start phototherapy is

not clearly defined. The traditional approach is to initiate phototherapy

to maintain bilirubin level below 20 mg/dL. Exchange transfusion is

considered if the serum level remains elevated (22 to 28 mg/dL) despite

appropriate phototherapy.

Clinical Pearls

1. Physiologic jaundice in the

presence of a good hemoglobin level is orange in color. It is often

visible when the bilirubin level exceeds 8 mg/dL. Jaundice associated

with anemia is usually lemon in color.

2. Bilirubin levels should be

modified for prematurity, sepsis, low birth weight, and other risk

factors when phototherapy or exchange transfusion is considered.

|

|

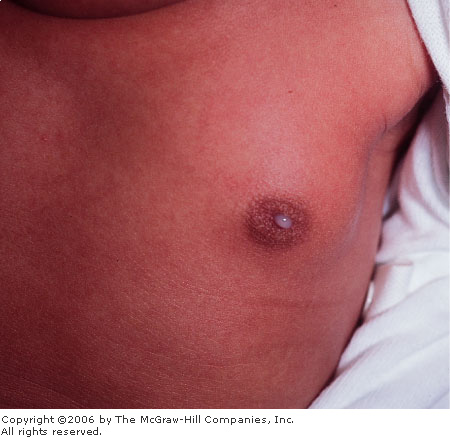

Neonatal Milk Production (Witch's Milk)

Associated Clinical Features

Because of transplacental

hormonal effects (maternal estrogens and possibly endogenous prolactin),

both sexes are equally liable to develop enlarged breasts. This

phenomenon occurs with or without galactorrhea in 60% of normal newborns.

After the first 48 h, the hypertrophied breasts may become engorged, and

a form of lactation occurs (Fig. 14.5). The engorgement and edema begin

to subside after the second week of life. The hypertrophy and

galactorrhea may persist up to 6 months in girls. These infants are

occasionally predisposed to infections (mastitis or abscess).

|

|

|

|

|

Witch's

Milk Milky fluid draining from

the nipple in a newborn. (Courtesy of Michael J. Nowicki, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Early mastitis with purulent

discharge may resemble normal neonatal milk production.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment is not necessary; reassurance

for parents is very important.

Clinical Pearl

1. Newborns with hypertrophied

mammary tissue and evidence of clear colostrum-like secretion in the

absence of erythema, tenderness, and/or fluctuation usually do not

present with neonatal mastitis.

|

|

Neonatal Mastitis

Associated Clinical Features

Neonatal mastitis is most common

in full-term females, particularly in their second or third week of life.

Clinically it manifests as swelling, induration, and tenderness of the

affected breast with or without erythema or warmth (Fig. 14.6). In some

cases purulent discharge may be obtained from the nipple. Bacteremia and

fever are rare. This infection is usually caused by Staphylococcus

aureus, coliform bacteria, or group B streptococcus. If treatment is

delayed, mastitis may progress rapidly with involvement of subcutaneous

tissues and subsequent toxicity and systemic findings.

|

|

|

|

|

Neonatal

Mastitis Neonate with

left-sided breast swelling, erythema, and purulent discharge.

(Courtesy of Raymond C. Baker, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

In the initial stages, neonatal

mastitis may mimic mammary tissue hypertrophy owing to maternal passive

hormonal stimulation. Minor trauma, cutaneous infections, and duct

blockage may precede this infection.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Institution of treatment is

important to avoid cellulitic spread and breast tissue damage. In cases

of mild cellulitis and no fluctuation, culture of nipple discharge and

antibiotic coverage (semisynthetic penicillin or first-generation

cephalosporins) completes the treatment. Adjustment of coverage may be

done once results of cultures or Gram's stain are available, especially

in the presence of gram-negative bacilli. If no organism is seen

initially, semisynthetic penicillin and an aminoglycoside or cefotaxime

should be used. In case of toxicity or subcutaneous spreading, a complete

sepsis workup should be performed, and hospitalization is usually

indicated. In cases of palpable fluctuation, prompt surgical incision and

drainage should be performed by a surgeon to avoid further damage of the

mammary tissue. Recovery is usually in 5 to 7 days.

Clinical Pearl

1. Consider mastitis in the

neonate with edema, induration, and tenderness of the breast tissue.

Erythema and fluctuation to palpation ensue if treatment is delayed.

|

|

Umbilical Cord Granuloma

Associated Clinical Features

Umbilical cord granuloma develops

in response to a mild infection at the base of the umbilical cord caused

by saprophytic organisms. Usually parents describe a persistent discharge

from the base of the cord. The granuloma is soft, pink, and vascular

(Fig. 14.7) and is the result of persistence of exuberant granulation

tissue.

|

|

|

|

|

Umbilical

Cord Granuloma Newborn infant

with umbilical cord demonstrating granuloma on base of umbilical

cord. (Courtesy of Michael J. Nowicki, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

An umbilical polyp is a rare

anomaly resulting from the persistence of the omphalomesenteric duct

(Figs. 14.8, 14.9) or the urachus and may have a similar appearance. This

polyp is usually firm and resistant, with a mucoid secretion. Omphalitis,

an infection secondary to gram-negative organisms, should be considered.

|

|

|

|

|

Omphalomesenteric

Duct This red mass resembling

a granuloma was found to be an omphalomesenteric duct. (Courtesy of

Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fistulogram A fistulogram confirms the diagnosis of

persistent omphalomesenteric duct. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD,

MS.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Cleaning and drying of the

umbilical cord base with alcohol several times a day may prevent

granuloma formation. Cauterization of the granuloma with silver nitrate

is the treatment of choice. It is important to protect the surrounding skin

to avoid chemical burns produced by the excess of silver nitrate.

Clinical Pearls

1. Commonly the only sign of

granuloma formation is the presence of nonpurulent discharge noted in the

diaper area in contact with the umbilicus.

2. Omphalitis presents with

redness on the abdominal wall and often with a purulent discharge from

the umbilicus.

|

|

Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis (HPS)

Associated Clinical Features

HPS is characterized by

postprandial, nonbilious vomiting due to hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the

pyloric musculature, producing gastric outlet obstruction. It is usually

diagnosed in infants from birth to 5 months, most commonly at 2 to 8

weeks of life. The vomiting progresses to forceful and is described as

projectile (although this pattern is not always present). There is a

familial incidence, and white males are more frequently affected. During

the physical examination, peristaltic waves may be observed traveling

from the left upper to right upper quadrants (Fig. 14.10). The

hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the antral and pyloric musculature

produces the "olive" to palpation (best palpated after emptying

the stomach with a nasogastric tube). Because of persistent vomiting,

hypochloremic alkalosis with various degrees of dehydration and failure

to thrive may occur when this is not diagnosed early. The finding of the

pyloric olive is pathognomonic. Ultrasound and fluoroscopy are useful

diagnostic tools to confirm the diagnosis when the olive is not evident.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gastric

Wave of Hypertrophic Stenosis

A gastric wave can be seen traversing the abdomen in this series of

photographs of a patient with HPS. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD,

MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Intestinal obstruction, atresia,

malrotation with volvulus, hiatal hernia, gastroenteritis, adrenogenital

syndrome, increased intracranial pressure, esophagitis, sepsis,

gastroesophageal reflux, and poor feeding technique should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Once the diagnosis is considered,

treatment includes correction of fluids and electrolyte imbalance

followed by surgical referral for curative pylorotomy. Patients benefit

from a nasogastric tube on low intermittent suction.

Clinical Pearls

1. Any infant in the first 2

months of life who presents with postprandial vomiting, some evidence of

failure to gain weight, easy refeeding, hunger after vomiting, and

infrequent bowel movements should be carefully evaluated to rule out the

possibility of HPS.

2. Clinical suspicion can be

heightened with serial examinations and observation of the child after

oral fluid challenges for persistent projectile vomiting.

3. Correction of any

electrolyte imbalance should occur prior to surgery.

|

|

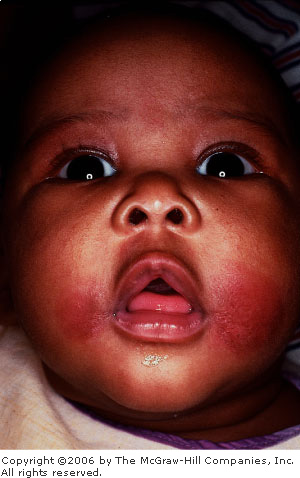

Erythema Infectiosum (Fifth Disease)

Associated Clinical Features

Erythema infectiosum is a viral

infection caused by parvovirus B19. It is characterized by an eruption

that presents initially as an erythematous malar blush followed by an

erythematous maculopapular eruption on the extensor surfaces of

extremities that evolves into a reticulated, lacy, mottled appearance

(Fig. 14.11). It may present with low-grade fever, malaise, general

aches, arthritis, or arthralgias.

|

|

|

|

|

Fifth

Disease Toddler with the

classic slapped-cheek appearance of fifth disease caused by

parvovirus B19. Also note the lacy reticular macular rash on the

shoulder and upper extremity. (Courtesy of Anne W. Lucky, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Morbilliform eruptions may be

caused by viruses such as measles, rubella, roseola, and infectious

mononucleosis. Bacterial infections (i.e., scarlet fever), drug

reactions, and other skin conditions such as guttate psoriasis, papular

urticaria, and erythema multiforme are included in the differential.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

There is no specific treatment.

Once the rash appears, the patient is no longer contagious. It is

important to educate the patient and family about the possible risk of

B19 virus as a cause of hydrops fetalis or fetal deaths early in

pregnancy and the issue of an aplastic crisis in patients with

hematologic problems such as sickle cell disease, hereditary

spherocytosis, other hemolytic anemias, or immunosuppressed host.

Clinical Pearl

1. Classically this infection

begins with the intense redness of both cheeks ("slapped-cheek

appearance"). Although the eruption tends to disappear within 5 days

of the initial presentation, recrudescences may occur with exercise,

overheating, and sunburns as a result of cutaneous vasodilatation.

|

|

Roseola Infantum (Exanthem Subitum)

Associated Clinical Features

The typical presentation of

roseola infantum is that of a child with a 2- or 3-day history of fever

and irritability. This is followed by rapid defervescence and the

appearance of an erythematous morbilliform eruption (Fig. 14.12). It has

been associated with various viral agents such as parvovirus, echovirus,

and other enteroviruses. Most recently it has been associated with

herpesvirus 6.

|

|

|

|

|

Roseola

Infantum (Exanthem Subitum)

Toddler with maculopapular eruption of roseola. (Courtesy of Raymond

C. Baker, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Morbilliform eruptions may be

caused by common viruses such as measles, rubella, parvovirus B19, or

infectious mononucleosis. Bacterial infections (e.g., scarlet fever),

drug reactions, and other skin conditions such as guttate psoriasis,

papular urticaria, and erythema multiforme may be included in the

differential.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

As with most viral infections,

only supportive therapy is necessary. Special attention should be paid in

maintaining fluid intake, fever control for the patient's comfort, and

parental education about the benign, self-limiting characteristics of

this illness.

Clinical Pearls

1. The presence of mild eyelid

edema with posterior cervical adenopathy in the febrile child without a

source may be early indicators for the diagnosis of roseola. Once the

fever ends and the rash appears, the diagnosis is clinically confirmed.

2. Rashes during the febrile

course of an illness are not roseola.

|

|

Impetigo

Associated Clinical Features

Impetigo is a bacterial infection

of the skin produced by Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus

aureus. It begins as small vesicles or pustules with very thin roofs

that rupture easily with the release of a cloudy fluid and the subsequent

formation of a honey-colored crust (Figs. 14.13, 14.14). Often the

lesions spread rapidly and coalesce to form larger ones.

|

|

|

|

|

Impetigo Young girl with crusting impetiginous lesions

on her chin. (Courtesy of Michael J. Nowicki, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bullous

Impetigo A child with

impetiginous lesions on the face. Note the formation of bullae.

(Courtesy of Anne W. Lucky, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Second-degree burns, cutaneous

diphtheria, herpes simplex infections, nummular dermatitis, and kerion

may present with crusts and be confused with impetigo.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Since these lesions are

contagious, good hand washing and personal hygiene should be discussed

with the patient and family. Antibiotic coverage should be directed

against the organisms mentioned above. Effective oral agents include

erythromycin, first-generation cephalosporins, cloxacillin, or

amoxicillin with clavulanic acid. Topical agents such as mupirocin

ointment have proved to be as effective as oral antibiotics.

Clinical Pearls

1. A red, weeping surface and

the presence of moist, thin vesicles with honey-colored crusts makes the

diagnosis of impetigo.

2. Inflicted cigarette burns

may resemble the lesions of impetigo.

|

|

Kerion

Associated Clinical Features

A kerion consists of inflammatory

boggy nodules with pustules caused by an exaggerated host delayed

hypersensitivity response to infections with either Microsporum canis

or Trichophyton tonsurans. These lesions usually remain localized

to one area (Fig. 14.15). It appears 2 to 8 weeks after the initial

fungal infection and resolves over 4 to 6 weeks. If untreated, scarring

and hair loss may occur.

|

|

|

|

|

Kerion Occipital boggy swelling with hair loss

consistent with kerion. (Courtesy of Anne W. Lucky, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Bacterial pyoderma is commonly

mistaken for kerion but yields a purulent discharge when aspirated. The

diagnosis should be made on clinical appearance.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Topical agents have no role in

the treatment of tinea capitis or kerion. Griseofulvin for 4 to 6 weeks

is the treatment of choice. Ketoconazole has also been used. Viable

spores can be eradicated by adding selenium sulfide shampoo (2.5%) to

this therapy. In cases of severe inflammatory reaction, prednisone

combined with griseofulvin ensures a rapid resolution of the infection

and immunogenic reaction. Incision should be avoided to prevent scar

tissue.

Clinical Pearl

1. If a kerion happens to be

aspirated or incised, only serosanguineous fluid is obtained.

|

|

Varicella (Chickenpox)

Associated Clinical Features

Chickenpox results from a primary

infection with varicella virus and is characterized by a generalized

pruritic vesicular rash (Fig. 14.16), fever, and mild systemic symptoms.

The skin lesions have an abrupt onset, develop in crops, and evolve from

papules to vesicles (rarely bullae) and finally to crusted lesions within

48 h. The classic lesions are teardrop vesicles surrounded by an

erythematous ring (dewdrop on a rose petal) (Fig. 14.17). Secondary

bacterial infection of these lesions can occur, causing cellulitis, which

may be severe. Other complications from varicella include encephalitis,

pancreatitis, hepatitis, pneumonia, arthritis, or meningitis. Cerebritis

(ataxia) may develop and is usually self-limiting.

|

|

|

|

|

Varicella

(Chickenpox) Multiple

umbilicated cloudy vesicles of varicella. (Courtesy of Lawrence B.

Stack, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Varicella

(Chickenpox) Vesicles in

different stages of maturation. Note the clear vesicle on an

erythematous base ("dewdrop in a rose petal") in the center

of the chest. (Courtesy of Judith C. Bausher, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Although several illnesses can

present with vesiculobullous lesions, the typical case of varicella is

seldom confused with other problems. Common viral infections that

manifest with vesicular rashes include herpes simplex, herpes zoster,

coxsackie, influenza, and echovirus infections or vaccinia. On occasion

varicella can be confused with papular urticaria.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Most patients do not develop any

complications. Treatment should be symptomatic and directed to pruritus

and fever control (avoid salicylates because of their association with

Reye's syndrome). Oral acyclovir given within 24 h of the onset of the

illness may result in a modest decrease in the duration of symptoms and

in the number and duration of skin lesions. Acyclovir is not recommended

routinely for treatment of uncomplicated varicella in an otherwise

healthy child. In the immunocompromised host, VZIG (varicella zoster

immunoglobulin) and intravenous acyclovir are effectively used.

Clinical Pearl

1. Skin lesions in varicella

present in successive crops, so that papules, vesicles, and crusted

lesions may all be present at the same time. The earliest lesions may

begin at the hairline on the nape of the neck.

|

|

Measles

Associated Clinical Features

Measles presents as an acute

febrile illness with a 3- to 4-day prodromal period characterized by

cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis associated with fever (101° to 104°F),

chills, and malaise. Koplik's spots, the pathognomonic sign of measles,

appear as 1- to 3-mm white elevations on the buccal mucosa (Fig. 14.18).

They usually present 1 to 2 days before the development of the

characteristic erythematous maculopapular rash. This rash appears during

the third or fourth day of the illness. It usually begins around the

hairline, behind the earlobes, and spreads downward (Fig. 14.19). It

tends to fade in the same order it appears. Most cases recover without

complications; others may develop otitis media, croup, pneumonia,

encephalitis, and rarely subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), a

very late complication.

|

|

|

|

|

Koplik's

Spots Tiny white dots

(Koplik's spots) are seen on the buccal mucosa. (Courtesy of Lawrence

B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Measles School-age child with a morbilliform rash on

his face consistent with measles. (Courtesy of Javier A. Gonzalez del

Rey, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of the

characteristic rash is vast and includes exanthem subitum; rubella;

infections caused by echovirus, coxsackie and adenoviruses;

toxoplasmosis; infectious mononucleosis; scarlet fever; Kawasaki disease;

drug reactions; Rocky Mountain spotted fever; and meningococcemia.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Supportive therapy includes bed

rest, antipyretics, and adequate fluid balance. Complications should be

treated according to the presentation. Current available antiviral

compounds are not effective. The use of gamma globulins and steroids in

SSPE is limited. Passive immunization is effective for prevention and

attenuation of measles if given within 5 days of the initial exposure.

During outbreaks, measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine is given earlier

than 15 months and may need to be repeated. A second dose is recommended

after the primary series for those born after 1956. This is given at age

11 or 12 years or by entry to junior high school.

Clinical Pearls

1. The classic presentation

includes a prodromal phase (fever, hacking cough, coryza, and

conjunctivitis), Koplik's spots followed by an abrupt temperature rise,

and a rash spreading in a caudal distribution.

2. Examination of the oral

mucosa to identify Koplik's spots may diagnose measles early if performed

in all children with an acute febrile illness.

|

|

Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease

Associated Clinical Features

Hand, foot, and mouth disease is

a seasonal (summer–fall) viral infection caused by coxsackievirus

A16. It is characterized by fever, malaise, and anorexia over 1 to 2

days, followed by oral lesions (small, red macules that evolve into small

vesicles 1 to 3 mm in diameter) in the posterior oropharynx (Fig. 14.20).

This enanthem is then followed by a superficial, nonloculated vesicular

eruption on the hands and feet (3 to 7 mm) (Figs. 14.21 and 14.22). These

may also be present on the buttocks, face, and legs.

|

|

|

|

|

Hand,

Foot, and Mouth Disease

Discrete vesicular erosions on the posterior oropharynx and soft

palate secondary to coxsackievirus. (Courtesy of James F. Steiner,

DDS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hand,

Foot, and Mouth Disease

Erythematous vesicular rash scattered on the palms, consistent with

coxsackievirus. (Courtesy of Michael J. Nowicki, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hand,

Foot, and Mouth Disease

Vesicular rash of the feet consistent with coxsackievirus. (Courtesy

of Raymond C. Baker, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Herpes simplex, varicella,

varicella zoster, influenza, echovirus infections, vaccinia, and other

coxsackieviruses should all be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Supportive therapy, especially

fluid maintenance and fever control for the patient's comfort, is the

mainstay of treatment. The duration and characteristics of the illness

should be discussed with the parents. In the majority of cases, the

course is self-limited and the prognosis excellent. On rare occasions,

secondary complications such as myocarditis, pneumonia, and

meningoencephalitis may occur.

Clinical Pearl

1. The individual lesions are

usually seen on the palms, fingertips, and soles. Oral cavity lesions

appear as discrete oval erosions and most are classically seen in the

posterior oropharynx and soft palate.

|

|

Cold Panniculitis (Popsicle Panniculitis)

Associated Clinical Features

Cold panniculitis is an acute

cold injury to the fat of the cheeks in infants. It manifests as red,

indurated nodules and plaques on exposed skin, especially the face (Fig.

14.23). These lesions appear 1 to 3 days after exposure and gradually

soften and return to normal over 1 or more weeks. This phenomenon is

caused by subcutaneous fat solidification when exposed to low

temperature. It is more frequent in children than in adults.

|

|

|

|

|

Cold

Panniculitis Infant with cheek

erythema, swelling, and discoloration consistent with popsicle

panniculitis or cold injury. (Courtesy of Anne W. Lucky, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Facial cellulitis, trauma,

pressure erythema, giant urticaria, and contact dermatitis may have a

similar presentation.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment is not necessary;

parental reassurance is very important.

Clinical Pearl

1. Because these lesions may

also be painful, the differentiation of cold panniculitis from cellulitis

may be difficult on occasion. The absence of systemic symptoms,

especially fever, and the history of cold exposure are very suggestive of

cold panniculitis.

|

|

Herpetic Gingivostomatitis

Associated Clinical Features

Herpetic gingivostomatitis is a

viral infection commonly seen in infants and children; it is caused by

herpes simplex. Patients usually present with fever, malaise, cervical

adenopathy, and pain in the mouth and throat on attempting to swallow.

Vesicular and ulcerative lesions appear throughout the oral cavity. The

gingiva becomes very friable and inflamed, especially around the alveolar

rim. Increased salivation with foul breath may be present. Although fever

disappears in 3 to 5 days, children may have difficulty eating for 7 to

14 days. Sometimes, autoinoculation produces vesicular lesions on the

fingers (herpetic whitlow) (Fig. 14.24).

|

|

|

|

|

Herpetic

Gingivostomatitis Multiple

oral vesicular lesions consistent with herpes gingivostomatitis.

Vesicular lesions from autoinoculation are present on the finger

(herpetic whitlow). (Courtesy of Michael J. Nowicki, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Vincent's angina, aphthous

stomatitis, erythema multiforme, Behçet's disease, and other viral

infections such as herpangina and hand, foot, and mouth disease

(coxsackieviruses) should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

No specific treatment is

available. In immunocompromised patients, acyclovir should be considered.

In the normal host, fluid balance should be maintained throughout the

illness. Because of ulcerative lesions, avoidance of citrus juices or

spicy food prevents pain on swallowing. Clear fluids, ice pops, and ice

cream may be used in small children. Not infrequently, admission for

intravenous hydration is necessary. Adequate fever control is also necessary

for patient comfort and to avoid an increase in fluid losses. Pain

control may be achieved by using mixtures of antihistamine

(diphenhydramine elixir) and antacids (1:1) applied to lesion with

Q-tips. In small children, local application of viscous lidocaine

(Xylocaine) should be avoided, since patients may develop toxic plasma

levels due to an altered absorption from an inflamed oral mucosa.

Clinical Pearl

1. Most of these lesions are in

the anterior two-thirds of the oral cavity. Posterior lesions sparing the

gingiva are most commonly seen in coxsackievirus infections.

|

|

Urticaria

Associated Clinical Features

Urticaria is a localized,

edematous skin reaction from histamine release that usually follows an

infection, insect sting or bite, ingestion of certain foods, or

medications. It is characterized by a sudden onset of pruritic,

transient, well-circumscribed wheals scattered over the body. These are

flat-topped and may vary from pinpoint size to several centimeters in

diameter. They usually have a central clearing and peripheral extension

and can have tense edema (Fig. 14.25). Most urticarial reactions last 24

to 48 h; on rare occasions, they may take weeks to resolve. Rarely, there

may be systemic reactions such as wheezing, stridor, or angioedema.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Urticaria Preschool child with annular, raised pruritic

lesions with the central clearing and tense edema of polycyclic

urticaria. The lesions had completely disappeared after about 5 min.

(Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Erythema multiforme, arthropod

bites, dermatographism, contact dermatitis, reactive erythemas, allergic

vasculitis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, mastocytosis, and pityriasis

rosea can all present with a similar-appearing rash.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment is symptomatic. Oral

antihistamines are useful in the control of pruritus. If a systemic

reaction is also part of the initial presentation, epinephrine and

steroids should be added to the therapy. In most cases it is very

difficult to identify the etiologic factor. Unless there is evidence of

acute angioedema, most cases can be discharged home on oral

antihistamines.

Clinical Pearl

1. Erythema multiforme can be

commonly mistaken for polycyclic urticaria (multiple red wheals of

different sizes). Clinicially these two entities can be differentiated by

the duration and color of the lesions. In urticaria, the center is clear

and each lesion usually lasts a few hours. In erythema multiforme, the

center is dusky and the lesion remains in the same place for several days

to weeks.

|

|

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome

Associated Clinical Features

Staphylococcal scalded skin

syndrome is caused by a staphylococcal toxin-producing strain. It may

present with fever, malaise, and irritability following an upper

respiratory infection. Patients develop a diffuse faint erythematous rash

that becomes tender to touch. Crusting around the mouth, eyes, and neck

is not uncommon. Within 2 to 3 days, the upper layers of dermis may be

easily removed; finally a flaccid bulla develops with subsequent

exfoliation of the skin (Fig. 14.26). In young patients, this exfoliation

may involve a large surface area with significant fluid and electrolyte

losses.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Staphylococcal

Scalded Skin Syndrome Toddler

with diffuse macular peeling eruption consistent with scalded skin

syndrome from Staphylococcus aureus. (Courtesy of Judith C.

Bausher, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Toxic epidermal necrolysis,

exfoliative erythroderma, bullous erythema multiforme, bullous

pemphigoid, bullous impetigo, sunburn, acute mercury poisoning, toxic

shock syndrome, and scarlet fever should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment is directed at the

eradication of Staphylococcus, thus terminating the production of toxin.

Synthetic penicillins should be used intravenously. Admission is usually

necessary, especially in young infants. This age group requires careful

attention to fluid and electrolyte losses and the prevention of secondary

infection of the affected skin.

Clinical Pearl

1. The wrinkling or peeling of

the upper layer of the epidermis (pressure applied with a Q-tip or gloved

finger) that occurs within 2 or 3 days of the onset of this illness is

known as Nikolsky's sign.

|

|

Meningococcemia

Associated Clinical Features

Meningococcemia is an acute

febrile illness with generally rapid onset of marked toxicity, purpura,

and petechiae (Fig. 14.27). It progresses rapidly to hypotension with

multisystem failure. In cases of fulminant disease, this shock stage is

accompanied by disseminated intravascular coagulation and massive mucosal

hemorrhages. Occasionally there may be a specific prodrome with upper

respiratory infection and malaise.

|

|

|

|

|

Meningococcemia Diffuse petechiae in a patient with

meningococcemia. (Courtesy of Richard Straight, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Gonococcemia, Haemophilus

influenzae infection, pneumococcemia, Rocky Mountain spotted fever,

sepsis with thrombocytopenia or disseminated intravascular coagulation

(DIC), endocarditis, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, typhoid fever, leukemia,

hemorrhagic measles, or hemorrhagic varicella may have a similar

appearance.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

In stable patients in whom the

diagnosis of meningococcemia is entertained, cultures of blood, spinal

fluid, nasopharynx, complete blood count, platelet count, and coagulation

studies should be obtained. Consider arterial blood gas, liver function

tests, and other studies as indicated. These patients should be admitted

for close monitoring to institutions capable of delivering critical care

services. Broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics should be used in the

initial coverage until the organism is identified and sensitivities are

available. In the unstable septic patient, adequate ventilation and

cardiac function must be ensured in addition to performing the above tests

and treatment. Hemodynamic monitoring and support (fluids and vasoactive

drugs) are of paramount importance in the management. Peripheral and

central venous catheters and urinary and arterial catheters are usually

necessary for optimal care of these patients.

Clinical Pearls

1. Skin scrapings of the

purpuric lesion can be microscopically examined for the presence of

gram-negative diplococci and may be cultured for organisms.

2. A child with a fever and a

petechial rash must be presumed to have meningococcemia.

|

|

Scarlet Fever

Associated Clinical Features

Scarlet fever manifests itself as

erythematous macules and papules that result from an erythrogenic toxin

produced by a group A streptococcus. The most common site for invasion by

this organism is the pharynx and occasionally skin or perianal areas. The

disease usually occurs in children (2 to 10 years of age) and less

commonly in adults. The typical presentation of scarlet fever includes

fever, headache, sore throat, and malaise followed by the scarlatiniform

rash (Fig. 14.28). The rash is typically erythematous; it blanches (in

severe cases may include petechiae), and—owing to the grouping of

the fine papules—gives to the skin a rough, sandpaper-like texture

(Fig. 14.29). On the tongue, a thick, white coat and swollen papillae

give the appearance of a strawberry ("strawberry tongue").

|

|

|

|

|

Scarlatina Erythematous scarlatiniform rash of scarlet

fever. (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sandpaper

Rash Typical sandpaper rash of

scarlet fever. The grouping of the fine papules gives the skin a

rough, sandpaper-like texture. (Courtesy of Jeffery S. Gibson, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

A similar syndrome is caused by

staphylococci producing an exfoliative exotoxin, which can be

differentiated from the streptococcal infection because of the absence of

pharyngitis, strawberry tongue, and negative cultures. Enteroviral

infections, viral hepatitis, infectious mononucleosis, toxic shock

syndrome, drug eruptions, rubella, mercury intoxication, and

mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Penicillin, either benzathine

penicillin G or oral penicillin, to maintain levels for 10 days is the

key to therapy. Alternatives include erythromycin or clindamycin in

penicillin-allergic patients.

Clinical Pearls

1. Petechiae (commonly found as

part of the scarlatiniform eruption) in a linear pattern seen along the

major skin folds in the axillae and antecubital fossa are known as

"Pastia's lines" (Fig. 14.30).

2. In black skin, the rash may

be difficult to differentiate and may consist only of punctate papular

elevations called "goose flesh."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pastia's

Lines Confluent petechia in a

linear pattern in the antecubital fossa consistent with Pastia's

lines are seen in these patients with scarlet fever. Top: The forearm

on the right belongs to the patient's sister and does not show

Pastia's lines. Bottom: Pastia's lines in a Caucasian patient. A

classic sandpaper rash is also evident on the arm and trunk.

(Courtesy of Stephen Corbett, MD.)

|

|

|

|

Blistering Distal Dactylitis

Associated Clinical Features

Blistering distal dactylitis is a

cellulitis of the fingertips (Fig. 14.31) caused by beta-hemolytic

streptococcal and, in rare occasions, by Staphylococcus aureus

infections. The typical lesion is a fluid-filled, tense blister with

surrounding erythema located over the volar fat pad on the distal portion

of the fingers. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes and gram-positive cocci can

be found in the Gram's stain of the purulent exudate from the lesion.

|

|

|

|

|

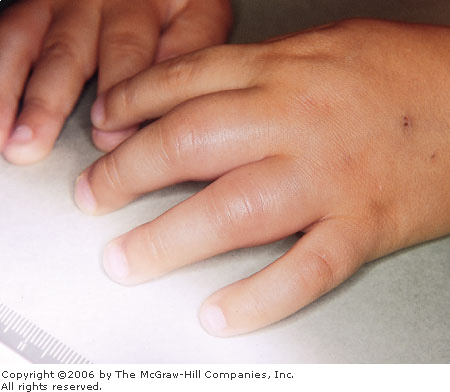

Blistering

Distal Dactylitis Blistering

rash of the distal fingers with surrounding erythema typically caused

by Streptococcus. Note the location of the rash over the volar

finger pad. (Courtesy of Anne W. Lucky, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Bullous impetigo, burns, friction

blisters, and herpetic whitlow should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

There is usually a rapid response

to incision and drainage of the blister and a 10-day course of antibiotic

therapy (dicloxacillin, cephalexin, or erythromycin).

Clinical Pearl

1. This diagnosis should be

entertained in any child presenting with a tender, cloudy, fluid-filled

blister of the fingertips or toes.

|

|

Strawberry Hemangioma

Associated Clinical Features

Strawberry hemangioma often

appears as small telangiectatic papules or a patch surrounded by an area

of pallor. These lesions grow and become vascularized during the first 2

months of life. The classic lesion is a raised gray to reddish nodule

with defined borders (Fig. 14.32). It commonly regresses in almost all patients

by 2 to 3 years of age. In a few cases, very large vascular lesions can

cause platelet trapping or high-output cardiac failure. Localized

hemangiomas can affect the airway, eyes, or other areas where they occur.

|

|

|

|

|

Strawberry

Hemangioma Raised umbilicated

vascular lesion on the right forehead consistent with strawberry

hemangioma. (Courtesy of Anne W. Lucky, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Malignant vascular tumors,

pyogenic granulomas, and giant melanocytic birthmarks should be

considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Most cases require no therapy

because strawberry hemangiomas usually regress without residua. Treatment

is indicated when there is an obstruction of a vital orifice (i.e.,

airway, mouth, or nares) or vision (eyelids) or if hematologic or

cardiovascular complications are present. Parental reassurance is

important because there is great pressure to treat for cosmetic reasons.

Steroids, liquid nitrogen, grenz-ray therapy, and pulse dye laser are

some of the different therapeutic modalities used in its treatment. In

complex cases, dermatologic consultation is recommended.

Clinical Pearl

1. The diagnosis of strawberry

hemangioma should always be considered in the presence of any purplish,

red, raised, tumorlike lesion not present at birth that appears in the

first month of life.

|

|

Orbital and Periorbital (Preseptal) Cellulitis

Associated Clinical Features

Orbital cellulitis is a serious

bacterial infection characterized by painful purple-red swelling of the

eyelids, restriction of eye movement (Fig. 14.33), proptosis, and a

variable degree of decreased visual acuity. It may begin with eye pain

and low-grade temperature. In general it is caused by Staphylococcus

aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus, or Pneumococcus.

It usually follows an upper respiratory tract infection or sinusitis but

can occur from local trauma. If not treated promptly, it can lead to

abscess formation, blindness, or meningitis. Periorbital (preseptal)

cellulitis usually presents with edema and erythema of the eyelids (Fig.

14.34), minimal pain of the affected area, and fever. Proptosis or

ophthalmoplegia are not characteristic. Common organisms are H.

influenzae type B or Pneumococcus. In cases of eyelid trauma,

S. aureus and group A streptococcus are the most common pathogens.

|

|

|

|

|

Orbital

Cellulitis Left orbital

cellulitis with decreased range of motion secondary to edema. Note

the infected conjunctiva. (Courtesy of Javier A. Gonzalez del Rey,

MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Periorbital

Cellulitis Left periorbital

cellulitis with edema and erythema of the eyelids. Note that the

conjunctiva is clear and not infected. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop,

MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Erysipelas, allergic reactions,

trauma, sunburn, frostbite, chemical burns, subperiosteal abscess, and

cavernous sinus thrombosis should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Parenteral antibiotic coverage

with broad-spectrum antistaphylococcal coverage, ophthalmologic

consultation, and admission are indicated in cases of orbital cellulitis.

Computed tomography of the orbit is necessary in certain cases to rule

out the possibility of an abscess requiring surgical drainage. In febrile

or ill-appearing patients with periorbital cellulitis, admission with

broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy is indicated. This coverage can be

adjusted once results of cultures are available. Mild cases of preseptal

cellulitis (especially those with history of trauma, e.g., abrasion,

insect sting) can be treated as outpatients with close follow-up.

Adequate coverage for Staphylococcus and Streptococcus is

necessary.

Clinical Pearls

1. Periorbital cellulitis

presents with circumferential redness, edema, and tenderness in the

febrile toddler. Orbital cellulitis must be considered if there is eye

pain or limitation of globe motion.

2. The conjunctiva is typically

clear with periorbital cellulitis.

|

|

Cystic Hygroma (Lymphangiomas)

Associated Clinical Features

Cystic hygromas are lymphatic

tumors found in the head and neck region (Fig. 14.35). They present as

nontender or nonpainful, compressible, unilocular or multilocular masses

with thin, transparent walls and are filled with straw-colored fluid.

Unlike hemangiomas, these lesions rarely undergo spontaneous regression.

The vast majority tend to grow and infiltrate adjacent structures. In

cases where the tongue is involved, they may produce tracheal compression

and respiratory difficulty.

|

|

|

|

|

Cystic

Hygroma A bright,

supraclavicular, soft, boggy, compressible mass consistent with

cystic hygroma. (Courtesy of Richard M. Ruddy, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Cavernous hemangiomas and

cavernous lymphangiomas should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Surgery is the treatment of

choice in the vast majority of cases, since these lesions do not regress

and may affect local tissues. Extent of the lesion should be evaluated

prior to its removal (x-rays and computed tomography). The earlier these

lesions can be removed, the better the cosmetic results.

Clinical Pearls

1. The diagnosis of cystic

hygroma should be considered in all cases of spongy, soft, tumor-like

masses in the neck that are filled with fluid. Such a lesion may appear

spontaneously during a coughing episode or after Valsalva as a mass in

the neck.

2. This "benign"

tumor can locally invade adjacent tissues and become life-threatening.

|

|

Cat Scratch Disease

Associated Clinical Features

Cat-scratch disease is a benign,

self-limited condition that manifests with regional lymphadenopathy (Fig.

14.36), which usually follows (1 to 2 weeks) a skin papule at the

presumed site of bacterial inoculation. A history of contact with or

scratch from a cat (Fig. 14.37) is usually present. Lymphadenopathy may

persist for months and in rare cases patients may develop complications

such as encephalitis, osteolytic lesion, hepatitis, weight loss, fever,

and fatigue. A skin test using cat-scratch antigen can identify the

etiology in suspected patients when confirmation of the diagnosis is needed.

|

|

|

|

|

Cat

Scratch Disease An

erythematous, tender, suppurative node is seen in a young febrile

patient with a history of cat scratch on the extremity. The node

required drainage 2 days later. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cat

Scratch Disease The

precipitating wound that caused the suppurative node in Fig. 14.36.

(Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Lymphogranuloma venereum,

bacterial adenitis, sarcoidosis, infectious mononucleosis, tumors (benign

or malignant), tuberculosis, tularemia, brucellosis, and histoplasmosis

should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The disease is usually

self-limited and management is primarily symptomatic. Parents and

patients should be reassured that the nodes are benign and frequently

resolve within 2 to 4 months. In cases of painful, fluctuant nodes,

needle aspiration may be necessary for relief of symptoms. Antibiotic

therapy should be considered for acutely or severely ill patients.

Several anecdotal reports have suggested that oral antibiotics such as

rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and ciprofloxacin or intravenous

gentamicin, cefotaxime, and mezlocillin may be effective. Surgical

excision of the affected nodes is generally unnecessary.

Clinical Pearl

1. Cat-scratch disease is the

most common cause of regional adenitis and should be considered in all

children or adolescents with persistent lymphadenopathy.

|

|

Epiglottitis

Associated Clinical Features

Epiglottitis is a

life-threatening condition characterized by sudden onset of fever,

toxicity, moderate to severe respiratory distress with stridor, and

variable degrees of drooling. The patient prefers a sitting position,

leaning forward in a sniffing position with an open mouth. This

symptomatology is the result of a direct infection and subsequent

swelling of the epiglottis and aryepiglottic folds (Figs. 14.38 and

14.39) from Haemophilus influenzae type B (HIB). However, since

the release of the vaccine in 1985, there has been a dramatic decrease in

the incidence of this disease. Adults have a more indolent course and are

infrequently protected by the vaccine. Other infectious causes include

staphylococcal or streptococcal disease, thermal epiglottitis, and Candida

in the immunocompromised host. Direct thermal injuries have been reported

as a noninfectious cause of epiglottitis. On x-ray, the epiglottis is

seen as rounded and blurred (thumbprint) (Fig. 14.40). Epiglottitis

frequently worsens to complete obstruction if not treated with

endotracheal intubation and antibiotics.

|

|

|

|

|

Epiglottitis Endoscopic view of almost complete airway obstruction

secondary to epiglottitis. Note the slit-like opening of the airway.

(Courtesy of Department of Otolaryngology, Childrens Hospital Medical

Center, Cincinnati, OH.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Epiglottitis Endoscopic view of the same patient

immediately after extubation. Although erythema and some edema

persist, the airway is widely patent. (Courtesy of Department of

Otolaryngology, Childrens Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Epiglottitis Lateral soft-tissue x-ray of the neck

demonstrating thickening of aryepiglottic folds and thumbprint sign

of epiglottis. (Courtesy of Richard M. Ruddy, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Acute infectious laryngitis,

acute laryngotracheobronchitis, acute spasmodic laryngitis, membranous

tracheitis, diphtheritic croup, aspiration of foreign body,

retropharyngeal abscess, and extrinsic or intrinsic compression of the

airway (tumors, trauma, cysts) should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Immediate intervention is required.

An artificial endotracheal airway must be established. If time and

clinical status permit, this should be done in the operating room or

designated area where advanced airway management with sedation but not

neuromuscular paralysis can be implemented. An experienced

anesthesiologist and surgeon should be available in case a surgical

airway is needed. Once the airway has been protected, the patient should

be sedated to avoid accidental extubation and adequate antibiotic therapy

should be immediately instituted (second- or third-generation

cephalosporins or ampicillin/chloramphenicol).

Clinical Pearls

1. Children with epiglottitis

usually present with respiratory distress of sudden onset and high fever.

Because of the inflammation of the epiglottis, they commonly refuse to

drink fluids secondary to pain.

2. Every effort should be made

to allow the child to remain undisturbed (in mother's lap) in a position

of comfort while urgent preparations are made for airway management. An

agitated child is at risk for suddenly losing the airway.

|

|

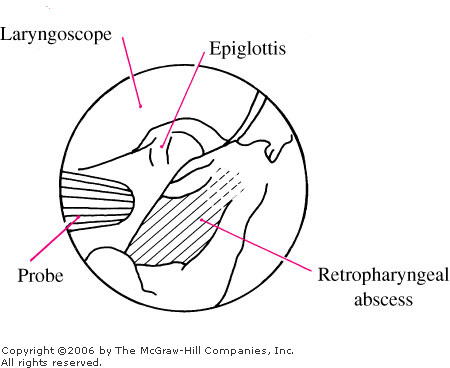

Retropharyngeal Abscess

Associated Clinical Features

Patients with a retropharyngeal

abscess usually present with fever, difficulty in swallowing, excessive

drooling, sore throat, changes in voice, or neck stiffness (Fig. 14.41).

The resultant edema (Fig. 14.42) is the result of a cellulitis and

suppurative adenitis of the lymph nodes located in the prevertebral

fascia and is seen on a soft tissue lateral x-ray of the neck as

prevertebral thickening (Fig. 14.43). The initial insult may be the

result of pharyngitis, otitis media, or a wound infection following a

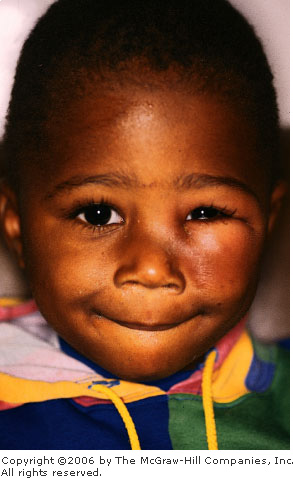

penetrating injury into the posterior pharynx. [It is helpful for the

examiner to be familiar with the normal laryngeal structures (Fig.

14.44)].

|

|

|

|

|

Retropharyngeal

Abscess This ill-appearing

6-year-old child presented with a several-day history of fever, neck

pain, sore throat, cough, and headache. Soft tissue lateral

radiography of the neck showed thickened prevertebral tissues

opposite C2-4. Computed tomography (CT) showed the airway narrowed to

a width of 5 mm within the oropharynx. (Courtesy of Mark Ralston,

MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

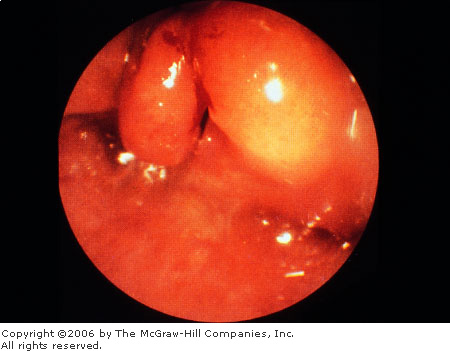

Retropharyngeal

Abscess Endoscopic view of a

retropharyngeal abscess. Note the massive swelling posteriorly.

(Courtesy of Department of Otolaryngology, Childrens Hospital Medical

Center, Cincinnati, OH.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

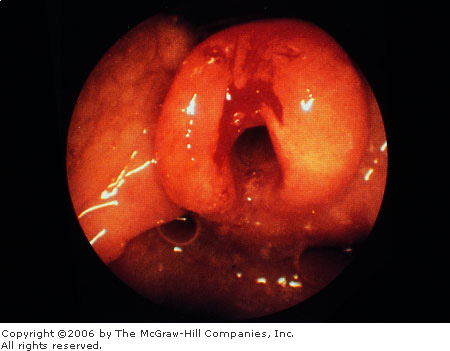

Retropharyngeal

Abscess Lateral soft tissue

neck x-ray demonstrating prevertebral soft tissue density consistent

with retropharyngeal abscess. (Courtesy of Richard M. Ruddy, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Normal

Laryngeal Structures

Endoscopic view of a normal epiglottis and surrounding structures.

(Courtesy of Department of Otolaryngology, Childrens Hospital Medical

Center, Cincinnati, OH.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Acute laryngotracheobronchitis,

epiglottitis, membranous tracheitis, acute bacterial laryngitis,

infectious mononucleosis, peritonsillar abscess, aspiration of foreign

body, and diphtheria should be considered. These patients may present

with stiff neck mimicking meningitis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

This illness requires immediate

intervention to prevent respiratory obstruction. The first step is to

evaluate the airway and establish an artificial one if necessary.

Antibiotic coverage should be initiated immediately (semisynthetic

penicillin or equivalent). Analgesia should be given as needed. If

obstruction is present or there is evidence of abscess, immediate

incision and drainage should be performed in the operating room. These

patients require hospitalization and immediate otolaryngologic or

surgical consultation.

Clinical Pearls

1. If the diagnosis of

retropharyngeal abscess is considered in a patient with the above

presentation, a lateral soft tissue neck x-ray may help to confirm the

diagnosis. In these cases, the retropharyngeal soft tissue at the level

of C-3 is > 5 mm, or more than 40% of the diameter of the body of C-4

at that level.

2. Computed tomography of the

neck is a useful tool to evaluate the extent of the lesion.

|

|

Membranous (Bacterial) Tracheitis

Associated Clinical Features

Membranous tracheitis is an acute

bacterial infection (Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilusinfluenzae,

streptococci, and pneumococci) of the upper airway capable of causing life-threatening

airway obstruction. It is considered a bacterial complication because it

almost always follows an apparent viral infection of the upper

respiratory tract. The infection produces marked swelling and thick,

purulent secretions of the tracheal mucosa below the vocal cords. The

secretions form a thick plug that, if dislodged, may ultimately lead to

an acute tracheal obstruction. Patients appear toxic, with fever and a

croup-like syndrome that can progress rapidly. The usual treatment for

croup is ineffective in these patients. The characteristic

"membranes" may be seen on x-rays of the airway as edema with

an irregular border of the subglottic tracheal mucosa. On direct

laryngoscopy, copious purulent secretions can be found in the presence of

a normal epiglottis.

Differential Diagnosis

Acute laryngotracheobronchitis,

retropharyngeal abscess, peritonsillar abscess, foreign-body aspiration,

and acute diphtheric laryngitis can present in a similar manner.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Otolaryngologic consultation

should be obtained as soon as the diagnosis is considered. Aggressive

airway management, including endotracheal intubation, may be needed to

protect the airway and allow for repeated suctioning to prevent acute

airway obstruction. The patient should be admitted to the intensive care

unit for close monitoring and sedation needs. Appropriate antibiotic

coverage against suspected organisms should be instituted immediately.

Clinical Pearls

1. Bacterial tracheitis often

presents with acute, severe airway obstruction after a short prodrome. It

should be suspected in all patients with an atypical croup-like

presentation: unusual age group, toxicity, not improving with routine

croup therapy, and unusual roentgenographic changes.

2. Up to 50% of soft tissue

films may delineate a subglottic membrane (Fig. 14.45).

|

|

|

|

|

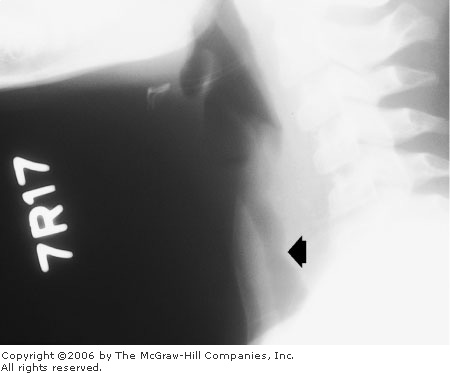

Membranous

Tracheitis Lateral soft tissue

x-ray of the neck reveals mild subglottic narrowing (arrow)

and membrane consistent with bacterial tracheitis. (Courtesy of Alan

S. Brodie, MD.)

|

|

|

|

Physeal Fractures: Salter-Harris Classification

Associated Clinical Features

There are several fractures

unique to children. These include physeal fractures, torus fracture,

greenstick fractures, avulsion fractures, and bowing fractures or

deformities. Physis fractures (growth plate fractures) are relatively

common because of weakness of the germinal growth plate. The

Salter-Harris (SH) classification was designed to describe each type of

physeal fracture, its prognosis, and its treatment (Fig. 14.46).

|

|

|

|

|

Salter-Harris

Fracture Classification

Salter-Harris classification for epiphyseal plate fractures.

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

SH type I: Fracture

that extends through the physis. It is a very difficult radiologic

diagnosis since the fracture may not be displaced. It is usually a

clinical diagnosis, but occasionally a physeal widening is observed on

the x-ray.

SH type II: Oblique

fracture extending through the metaphysis into the physis. It is the most

common type and the prognosis is good.

SH type III: This rare

type of fracture goes along the growth plate, then extends through the

epiphysis, ossification center, and articular cartilage into the joint.

SH type IV: Fracture

that extends from the metaphysis, across the growth plate and into the

joint.

SH type V: Crushing

injury to the growth plate.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Immobilization by splinting is

the treatment of choice in types I and II (minimum of 3 weeks). In these

cases, reduction is easy to achieve and maintain. Growth is unimpaired.

Types III and IV may require open reduction to avoid later traumatic

arthritis and, in some cases, growth arrest. Type V fractures are rare

and require very close follow-up because of arrest of growth caused by

the death of the germinal cells. Types III, IV, and V require immediate

orthopedic consultation.

Clinical Pearl

1. After initial assessment and

evaluation, always suspect SH type I if there is evidence of tenderness

around the growth plate area despite negative x-rays.

|

|

Acute Sickle Dactylitis (Hand-Foot Syndrome)

Associated Clinical Features

This painful condition is

commonly the first clinical manifestation of sickle cell disease. It

usually presents in children younger than 5 years of age. The pain and

abnormalities are the result of ischemic necrosis of the small bones

caused by the decreased blood supply as the bone marrow rapidly expands.

These children present acutely ill, with fever, refusal to bear weight,

and puffy hands and feet (Fig. 14.47). They may have a marked

leukocytosis, and the initial x-rays may be normal. It is not until 1 to

2 weeks later that subperiosteal new bone, cortical thickening, and even

complete bone destruction can be seen.

|

|

|

|

|

Acute

Sickle Dactylitis Bilateral

cylindrical swelling of soft tissue of the hands in sickle cell

disease consistent with vasoocclusive crisis or dactylitis. (Courtesy

of Donald L. Rucknagel, MD, PhD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Osteomyelitis, trauma, cold

injuries, acute rheumatic fever, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and

leukemias should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The most important aspects in the

treatment of vasooclusive crisis in sickle cell disease (hemoglobin SS)

include an adequate fluid balance, oxygenation, and analgesia. Therapy

should be individualized. Codeine, hydromorphone, morphine, and ketorolac

are analgesic agents commonly used in the treatment of children with

painful sickle crisis. In cases of dactylitis, very close follow-up is

necessary not only for the management of sickle cell disease but to

reevaluate the radiologic changes in small bones. In most instances, the

previously described changes disappear; however, in rare cases,

shortening of the fingers and toes has been described as the result of

severe bone infarcts.

Clinical Pearl

1. Most clinical manifestations

of sickle cell disease occur after the first 5 to 6 months of life. The

hemolytic anemia gradually develops over the first 2 to 4 months (changes

that follow the replacement of fetal hemoglobin by hemoglobin S) and

leads to the clinical syndromes associated with an increased SS hemoglobin.

|

|

Hair Tourniquet

Associated Clinical Features

A single strand of hair or thread

may encircle a finger, a toe, or the penis, leading to constriction (Fig.

14.48). Children in their first year of life are particularly at risk

from inadvertent attachment of a parent's hair or loose thread. The digit

appears edematous, erythematous, and painful. If not corrected vascular

compromise or infection can ensue.

|

|

|

|

|

Hair

Tourniquet A strand of hair

has encircled the middle toe in two places, causing erythema and

swelling. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Insect bites, trauma, or

cellulitis of the digit may have a similar appearance.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Visualization of the constricting

material may be difficult. Edema, erythema, and periarticular skin folds

may hide the hair or thread. It is imperative to carefully retract the

skin around the proximal aspect of the edema. A magnifying lens may be

helpful in identifying the band. Since the removal can be painful,

consider local digital block prior to removal. Using a small hemostat,

grasp a portion of the material, and then cut it with a surgical blade.

On occasions, depilatory agents have been used to remove hair fibers.

Elevation of the involved digit after removal of the constricting agent

provides resolution of the edema and erythema within 2 to 3 days. In some

cases the digit's blood supply may have been irreversibly compromised.

Subspecialty consultation should be considered whenever neurovascular

integrity is in question.

Clinical Pearl

1. In the vast majority of

cases, a clear line of demarcation can be identified between the normal

tissue and the affected area.

|

|

Failure to Thrive

Associated Clinical Features

Failure to thrive (FTT) is a

chronic pattern of inability to maintain a normal growth pattern in

weight, stature, and occasionally in head growth (Fig. 14.49). It is most

common in infancy, and the condition is nonorganic (50%), organic (25%),

or mixed (25%) in etiology. The diagnosis is made after complete history

and physical examination with comparison of the measurements of length

(supine in children <3 years of age), weight, and head circumference

(maximal occipital-frontal circumference) to standard measurements. In

cases of deficient caloric intake or malabsorption, the patient's head

circumference is normal and the weight is reduced out of proportion to

height. Subnormal head circumferences with weight reduced in proportion

to height and normal or increased head circumferences with weight

moderately reduced are usually indicative of an organic problem.

|

|

|

|

|

Failure

to Thrive This infant has not

been able to maintain a normal growth pattern and appears cachectic.

(Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of

failure to thrive is lengthy. Nonorganic disorders include poor feeding

technique, disturbed maternal-child interaction, emotional deprivation,

inadequate caloric intake, and child neglect. Organic causes are numerous.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Depending on history, physical

findings, and the social situation, some cases can be managed as

outpatients. The primary care provider can determine whether outpatient

management is indicated. For the vast majority of cases, if the diagnosis

of failure to thrive is made in the ED, admission is suggested to

complete the evaluation. This could be the only indication of a poor

social environment or inadequate access to medical care. Initial

laboratory investigations should include a complete blood count,

electrolytes, BUN and creatinine urinalysis, and stool examination if the

stool pattern is abnormal. More specific testing should be used only if

clinically indicated and targeted to the possible underlying cause. Early

involvement of social services may facilitate the evaluation and

follow-up. Treatment will vary according to the underlying disorder.

Clinical Pearl

1. Failure to thrive in

neglected children is accompanied by signs of developmental delays,

emotional deprivation, apathy, poor hygiene, withdrawing behavior, and

poor eye contact.

|

|

Nursemaid's Elbow (Radial Head Subluxation)

Associated Clinical Features

Nursemaid's elbow is a condition

that occurs commonly in children younger than 5 years of age who are

usually picked up or pulled by the arm while the arm is pronated. The

children present unwilling to supinate or pronate the affected elbow

(Fig. 14.50). Generally they keep the arm in a passive pronation and

develop pain over the head of the radius. Radiographic studies should be

considered only in patients with an unusual mechanism of injury or those

who do not become rapidly asymptomatic after the reduction maneuvers.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

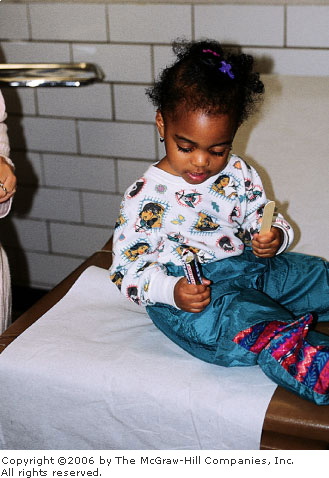

Nursemaid's

Elbow This child presents with

pseudoparalysis of the right arm after a pulling injury. Note how she

avoids use of the affected arm and preferentially uses the other arm.

(Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Radial head fracture or complete

dislocation, posterior elbow dislocation, condylar and supracondylar

fractures of the distal humerus, or buckle fracture of radius or ulna

should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Carefully palpate for tenderness

at all points of the affected arm. (No tenderness is found when not

rotating the involved arm.) Orthopedic consultation is generally not

indicated unless an underlying fracture is diagnosed. Reduction is

usually achieved by one of two maneuvers: (1) while supinating the

forearm, pressure is applied over the radial head and the elbow is

flexed, or (2) while holding the elbow in extension, hyperpronation of

the forearm is maintained until reduction is achieved. The patient

usually becomes asymptomatic after a few minutes (Fig. 14.51). When the

injury has been present for several hours, reduction may be difficult,

and it may take several hours to recover full function of the elbow.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

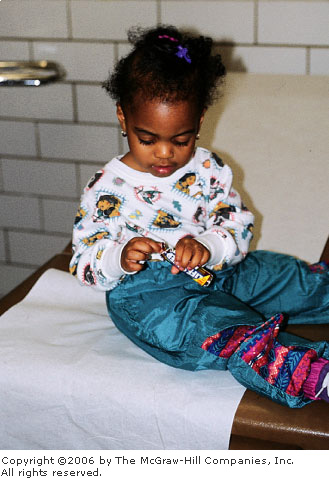

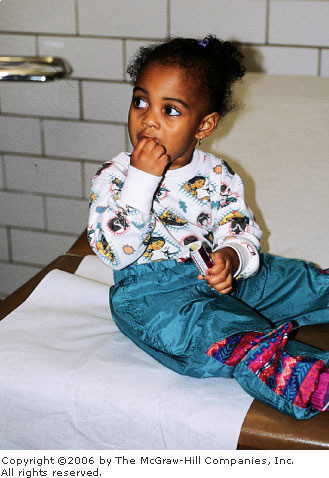

Nursemaid's

Elbow—Reduced After

reduction, there is initial reluctance to use the injured arm. With

distraction and encouragement, the patient demonstrates successful

use of the extremity. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Clinical Pearls

1. In any child (usually

between 1 to 5 years of age) who presents with sudden onset of elbow pain

and immobility following a traction injury, the diagnosis of nursemaid's

elbow should be strongly considered.

2. Nonjudgmental parental

education about the mechanism should be an integral part of the visit.

|

|

Nursing Bottle Caries

Associated Clinical Features

This extensive form of tooth

decay (generally in the necks of the teeth near the gingiva) is the

result of sleeping with a bottle containing milk or sugar-containing

juices. The condition generally occurs before 18 months of age and is

more prevalent in medically underserved children. Upper central incisors

are most commonly involved (Fig. 14.52).

|

|

|

|

|

Nursing

Bottle Caries Extensive tooth

decay from sleeping with a bottle containing milk or sugar-containing

juices. (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Less extensive tooth decay

(caries) may be seen in some infants who do not sleep with a bottle.

Caries can also result from tooth trauma. Dental referral is indicated.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Parental education and immediate

referral to a dentist is necessary to prevent complications. If

untreated, the caries may destroy the teeth and spread to contiguous

tissues. These patients have a high risk for microbial invasion of the

pulp and the alveolar bone, with the subsequent development of a dental

abscess and facial cellulitis. In these cases, aggressive treatment with

antibiotics (penicillin) and pain control, with prompt dental referral

for definitive care, is necessary.

Clinical Pearl

1. The role of the ED physician

is to recognize this pattern of dental decay (upper incisors most