|

Note: Large images and

tables on this page may necessitate printing in landscape mode.

Copyright

©2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved.

Emergency

Medicine Atlas > Part 2. Specialty

Areas > Chapter 15. Child Abuse > Physical

Abuse >

|

Inflicted Burns

Associated Clinical Features

Burns in children are frequently

the result of child abuse. The most common types of pediatric burns from

abuse are immersion burns and contact burns. Certain clues may assist the

physician in differentiating accidental burns from inflicted burns, but

often considerable doubt remains even after a careful evaluation.

In an immersion burn, a

thoughtful assessment of the pattern and location of the burns, as well

as of the unaffected areas, helps to differentiate between accidental and

inflicted burns. Postulate possible mechanisms for the injury and

correlate the assessment with the given history. A child who is held

firmly and deliberately immersed has burn margins that are sharp and

distinct. If the child has little opportunity to struggle, few or no

burns from splashing liquid will occur. In contrast, a child who

accidentally comes into contact with a hot liquid will move about in an

attempt to escape further injury. This movement causes the burn margins

to be less distinct and may result in additional small burns as hot

liquid splashes onto the skin. Children who are "dipped" into a

bath of hot water often show sparing of their feet and/or buttocks

because they are held firmly against the tub's bottom (Fig. 15.1). A

child who has had a hand dipped into hot water and held there may

reflexively close the fingers, sparing the palm and fingertips.

|

|

|

|

|

Immersion

Burns Immersion burns are

often associated with toilet training accidents. This girl was

plunged into hot water after soiling herself. She shows sparing of

the buttocks, which contacted the surface of the bathtub and avoided

being burned. (Courtesy of The Visual Diagnosis of Child Physical

Abuse. American Academy of Pediatrics, 1994.)

|

|

Contact burns usually have a distinct and

recognizable shape. Contact burn patterns most commonly associated with

abuse include burns from curling irons, hair dryers, heater elements, and

cigarettes (Figs. 15.2, 15.3, 15.4, 15.5). A child who has multiple

contact burns or burns to areas that are unlikely to come in contact with

the hot object accidentally should be evaluated for abuse.

|

|

|

|

|

Contact

Burn (Curling Iron) Burns on

the chest and abdomen from a curling iron. The burn pattern on the

injured skin indicates multiple contact burns from an object the size

and shape of a curling iron. Accidental curling iron burns occur, but

because this infant has so many burns, the injury is suspicious for

abuse. Child abuse should be suspected and reported unless the

historian can provide a plausible explanation of how these burns

occurred accidentally. (Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Contact

Burn (Hair Dryer) The heated

grid from the end of a hair dryer caused this child's burns. The burn

size and pattern marks of the burn matched exactly the hair dryer

grid that was found in the child's home. The history of accidental

injury was thought to be unlikely, and child abuse was suspected.

(Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Contact

Burn (Heater Grate) This child

was held against a heater grate. The pattern became more obvious with

the child's knee flexed—the position of the leg at the time of

the injury. (Courtesy of David W. Munter, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Contact

Burn (Cigarette) Cigarette

burns are circular injuries with a diameter of about 8 mm. It can be

difficult for the clinician to determine if the burn is from an

accidental injury or from abuse. Children who accidentally run into a

lit cigarette often have burns to the face or distal extremities.

Accidental burns may be less distinct and deep compared with

inflicted burns. A report of alleged child abuse should be made if

there are multiple cigarette burns, burns to locations unlikely to

come into contact with a cigarette accidentally, or other signs that

suggest abuse. (Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Some burn look-alikes may be

confused with child abuse. Impetigo (Fig. 15.6) may be mistaken for

healing cigarette burns, and bullous impetigo can resemble second-degree

burns. Contact dermatitis and cellulitis may resemble first-degree burns.

|

|

|

|

|

Impetigo These circular lesions of impetigo resemble

healing cigarette burns. (Courtesy of Michael J. Nowicki, MD.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Document thoroughly all burns

that may be due to abuse. Draw sketches and take photographs of the

injuries. Obtain a skeletal survey in children under the age of 2 years.

Report any suspected abuse immediately to the local child protective

agency before discharge from the ED. Provide standard burn therapy.

Clinical Pearls

1. Evaluate the alleged history

carefully and obtain sufficient details before making any judgment.

Assess whether the explanation and history that are given of the alleged

episode are inconsistent with the injuries and/or with the child's

developmental abilities. Suspect abuse if, without convincing

explanation, the historian alters the initial history.

2. Maintain a high index of

suspicion whenever caring for a pediatric burn patient. Look carefully

for other signs of abuse, such as bruising, fractures, or signs of

neglect.

3. Accidental burns from a

cigarette are usually single, superficial, and not completely round.

Common sites of accidental cigarette burns are the face, trunk, and

hands.

4. Report suspicions to the

mandated child protection agency whenever a burn may have been

deliberately inflicted.

5. Injuries due to suspected

child abuse may be photographed without parental consent in most states.

|

|

Inflicted Bruises and Soft-Tissue Injuries

Associated Clinical Features

Bruises are the most common

manifestation of physical child abuse. Child abuse should be suspected

whenever bruises are (1) over soft body areas, such as the thighs,

buttocks (Fig. 15.7), cheeks, abdomen, and genitalia, since common

childhood activities do not commonly cause trauma to these areas; (2)

more numerous than usual; (3) of different ages (suggests repeated

episodes of abuse); (4) the shape of objects such as belts, cords, or

hands (demonstrates that the injuries were inflicted) (Figs. 15.8, 15.9,

15.10); or (5) noted in young, nonambulating children (infants are not

capable of getting into accidents).

|

|

|

|

|

Gluteal

Fold Bruises This injury to

the buttocks demonstrates linear, parallel bruises near the gluteal

folds. Forceful spanking causes gluteal fold bruises. They do not

indicate a separate trauma in addition to the spanking. (Courtesy of

Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Looped

Pattern Markings Loop marks

are clearly seen within the bruising on this child's back. The loop

marks indicate that an extension cord, belt, or some similar object

was used to punish him. The color of the bruise is red, which

indicates that the injury is only a few days old. (Courtesy of Robert

A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hand-Print

Bruise Bruise from a slap

showing the outline of her father's hand is clearly seen on the back

of this adolescent. (Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Linear

Bruises These linear, parallel

bruises on the buttocks with unaffected skin between them are

indicative of an injury caused by an object. The width of the object

can be determined by measuring the space between the parallel lines.

Common objects that cause injuries like these, include belts,

fingers, cords, and rulers. (Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

The color of the ecchymosis will change as healing

progresses. New injuries are usually red and purple. They may also be

tender and swollen. Within a few days, the bruise may turn blue, then

green, then yellow, and finally brown. The shape and margins of the

bruise become less distinct as it heals. The time period in which these

color changes occur is variable. Some bruises resolve within a few days,

whereas others resolve over weeks. The amount of time until resolution

depends on factors such as the location, size, and depth of the injury.

Bite marks (Figs. 15.11, 15.12,

15.13) have special forensic characteristics that should be recorded. The

size, shape, and pattern of the injury can identify a specific

perpetrator. Most human bite injuries are caused by children, not adults,

but recognition of an adult bite is important because the injury

represents abuse. Compared with an adult's, the shape of a child's bite

is rounder. If the impressions from the canines are visible in the bite,

the perpetrator's age can be estimated. Most children under 8 years of

age have less than 3 cm between their canines. Some bites have saliva

within the center of the bite, which can also be used to identify the

perpetrator. Although some bite marks are immediately obvious during the

initial inspection, others can be difficult to recognize. If an adult

bite is suspected but unprovable because distinct impressions of the

teeth are absent, reexamination of the injury a few days later may

facilitate recognition and documentation.

|

|

|

|

|

Bite

Mark (Child) Distinct

impressions of teeth are seen in this injury. The shape of the injury

outlines the upper and lower oral arches. Note the size of the

mother's mouth in relation to the size of the bite on the neck,

making an adult mouth an unlikely source. (Courtesy of Kevin J.

Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bite

Mark (Adult) This bite mark is

on a young girl's breast. Note the larger size of the wound, which is

more consistent with an adult bite. (Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro,

MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bruises Bruises cover this child's left arm. The

circular bruise on the upper arm is a human bite. Saliva from the

perpetrator will usually be present within the center of the bite if

the injury is acute and the skin has not yet been washed. Moistened

swabs should be used to transfer the saliva from the skin onto the

gauze. This gauze must be saved for DNA analysis. As with all trace

evidence, the chain of evidence must be documented. (Courtesy of

Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

The bites of animals are usually

easy to distinguish from human bites. The size is usually smaller and the

shape of the arch mark is narrower than a human's. Sharp animal canines

often cause tearing of the skin instead of the crushing seen in human

bites.

Differential Diagnosis

Bleeding disorders—such as

idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), Henoch-Schönlein purpura, and

leukemia—can mimic child abuse. Folk remedies, such as cupping and

coining, may result in soft tissue findings that are not reportable as

abuse (see "Lesions Mistaken for Abuse," below).

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Completely undress the child and

look for additional signs of abuse (Figs. 15.14 and 15.15). Obtain a

complete history of all injuries. Sketch and photograph the injuries.

Obtain a platelet count and bleeding studies [prothrombin time and

partial thromboplastin time (PT and PTT)] to rule out a bleeding

diathesis as the cause of the findings. For children under 2 or 3 years

of age who have extensive injuries, obtain a skeletal survey, alanine

transferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), amylase, and

urinalysis.

|

|

|

|

|

Pinch

Marks on Pinna Children may be

pulled up or along by their ears, causing this injury. A child's ears

should be inspected for this injury whenever abuse is suspected.

(Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Strangulation

Bruise This child was beaten

while at the sitter's and suffered circumferential linear neck

abrasions consistent with attempted strangulation. There is also

occipital ecchymosis from the abuse. (Courtesy of Barbara R. Craig,

MD.)

|

|

If human bites are found or

suspected, consider consultation with a forensic dentist. If appropriate,

collect swabs for DNA forensic analysis from the center of unwashed,

fresh bites, which may contain saliva from the perpetrator.

Report suspected abuse to the

legally mandated child protection agency before the child is discharged

from the ED.

Clinical Pearls

1. Determination of the age of

a bruise is imprecise. Bruises that are "fresh" (< 48 h) are

usually recognizable because they are tender, red, and swollen.

Occasionally, bruises may not be visible for up to 48 h after an injury.

2. Children may deny abuse when

questioned because of threats made to them. The child in Fig. 15.16

initially denied that he had been gagged. He told the examining physician

that he had spilled some cleaning fluid onto his lips.

3. When a parent or caretaker

inflicts an injury while disciplining a child, the incident must be

reported to the local child protection agency. Even if corporal

punishment is lawful in a given state, the infliction of an injury is

never lawful.

4. Place a millimeter ruler or

coin next to a pattern injury before taking photographs so that

measurements can be made.

5. Consent is not required in

most states to photograph injuries suspicious for child abuse.

|

|

|

|

|

Gagging

Bruise This child had a sock

stuffed into his mouth and tied around his head. The bruises in the

corners of the child's mouth are indicative of gagging. Additionally,

there are circular bruises on his left and right cheeks caused from

the perpetrator's fingers while holding the child still to insert the

sock. Pattern markings within the bruises match the fabric pattern of

the sock. Photographs of these patterns should be obtained and

provided to the police. The red color of the bruises and the fresh

facial excoriations indicate that the injuries are recent. (Courtesy

of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

Lesions Mistaken for Abuse

Associated Clinical Features

Whenever bruising is excessive,

is not associated with a compatible history, or occurs in an unusual

distribution, seek a specific etiology. It may be appropriate to suspect

and report child abuse when these conditions exist but also consider

other diagnoses.

Common Childhood Bruising

Accidental trauma can result in a

bruise to any part of the body, but the forehead and the extensor

surfaces of the tibia, elbow, and knee are the most common locations.

When other areas of the body are bruised, etiologies other than accidental

bruising should be considered.

Mongolian Spots

Mongolian spots are bluish sacral

or truncal lesions, most often seen in non-Caucasian infants and young

children. They may be mistaken for bruises. Mongolian spots may be

limited to only a few lesions, or they may extend up the back and

shoulders of the child (Fig. 15.17).

|

|

|

|

|

Mongolian

Spots Numerous mongolian spots

on this youngster extend up the back and shoulders. (Courtesy of

Douglas R. Landry, MD.)

|

|

Cupping, Coining, and

Moxibustion

Asian families sometimes practice

traditional cures with their children, such as cupping, coining, and

moxibustion. Each of these practices leaves markings on the child's skin,

which may be interpreted as child abuse. In cupping, a flammable object

is ignited and placed into a cup. After the flames have extinguished, the

cup is inverted and placed onto the child's skin. As the warm air within

the cup cools, a vacuum is produced. This "cure" leaves

circular suction markings on the child's skin but should not be painful

to the child. Coining (Fig. 15.18) is done by rubbing a coin up and down

the child's back, just lateral to the spine. This results in petechiae

and chronic skin changes on the back. Coining should also not be painful

to the child. Neither of these practices should be reported as child

abuse. In moxibustion, a flammable object, such as a thread, is ignited

on or near the child's skin. Moxibustion may cause superficial burns.

Whether moxibustion is reported as child abuse would depend on the

physical findings and the judgment of the physician.

|

|

|

|

|

Coining

(Cheut Sah or Cao Gio) This

child has petechiae and bruising along her spine. Her parents were

practicing the Southeast Asian practice of coining, a healing remedy,

in which a coin is rubbed along the spine to heal an illness. Coining

should not be painful and is not considered abusive. (Courtesy of

Charles Schubert, MD.)

|

|

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is

a vasculitis of the small blood vessels. The skin lesions are usually

small, symmetric, palpable purpuras. They may appear in a linear pattern

and are often confined to the lower extremities (Fig. 15.19). Associated

symptoms may include joint and abdominal pain.

|

|

|

|

|

Henoch-Schönlein

Purpura (HSP) This child has

palpable purpura on the extensor surfaces of the legs. HSP should be

considered whenever there is symmetric ecchymosis along the extensor

surfaces of the extremities and buttocks. The illness is most often

seen in school-age children. Migratory arthritis and abdominal pain

may be present. (Courtesy of Ralph A. Gruppo, MD.)

|

|

Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic

Purpura

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic

purpura (ITP) is an acquired platelet disorder that results in abnormal

bleeding. It is most common in 1- to 4-year-old children. The presenting

complaint is most often abnormal bruising. The bruises can appear

anywhere on the body and are numerous, mimicking child abuse. The child

may also have epistaxis, hematuria, or other bleeding.

Hemophilia

Hemophilia is usually diagnosed

soon after birth because of abnormal bleeding. The ecchymosis and

soft-tissue swelling are greater than would be expected given the history

of trauma (Figs. 15.20, 15.21).

|

|

|

|

|

Hemophiliac

with Bruising This child's bruising

is due to factor VIII deficiency. The degree of bleeding within the

ecchymosis is more extensive than that seen in children without

coagulopathies. A history of other abnormal bleeding episodes or a

history that the child suffers from a coagulopathy is most often

obtained at the time of presentation. (Courtesy of Ralph A. Gruppo,

MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Grey

Turner's Sign This child

presented after a minor fall. This pattern of bruising (flank

ecchymosis) should alert the examiner to the possibility of

retroperitoneal bleeding, which was found on CT scan in this

hemophiliac patient. (Courtesy of Louis LaVopa, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic suspicion and

awareness of the above conditions is the most important step leading to

the correct diagnosis. HSP, mongolian spots, and cultural practices such

as moxibustion and cupping are diagnosed clinically. If ITP or other

thrombocytopenic disorders are suspected, a platelet count is diagnostic.

Newborns and infants with significant bleeding should have PT and PTT

tests to rule out a coagulopathy.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

A hematologist should be consulted

for children with platelet disorders and coagulopathies. HSP requires

supportive care and close follow-up. The most serious complication of HSP

is bowel obstruction from intussusception.

Clinical Pearls

1. Mongolian spots are noted

first in the newborn period.

2. Consider HSP in school-age

children with purpura of the lower extremities.

3. Consider ITP in preschool

children who have multiple ecchymosis and petechiae without other signs

or indications of abuse.

4. Vitamin K deficiency is a

cause of bleeding in infancy.

5. Trauma to the forehead may

cause bilateral eye ecchymosis (Fig. 15.22) within a few days and can be

mistaken for eye trauma.

|

|

|

|

|

Raccoon

Eyes, or Black Eyes The

etiology of this child's raccoon eyes was a forehead hematoma. He

fell onto his forehead a few days earlier and developed a hematoma, a

common accidental injury. As the hematoma healed, blood from the

hematoma tracked down along the facial soft tissues and settled under

his eyes. The resulting ecchymosis suggests that he was punched,

leaving him with two black eyes. The absence of other trauma about

the eyes—such as lacerations, abrasions, soft tissue swelling,

or eye injury—should cause the examiner to consider a diagnosis

other than direct trauma. Observation or palpation of forehead soft

tissue swelling results in the correct diagnosis. (Courtesy of Robert

A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

Fractures Suggestive of Abuse

Associated Clinical Features

Certain fractures should always

raise a suspicion of child abuse, such as metaphyseal corner fractures,

rib fractures, fractures in a nonambulating child, and untreated healing

fractures. Fractures incompatible with the history and those for which no

explanation is available are also suspicious of child abuse (Figs. 15.23,

15.24, 15.25, 15.26, 15.27, 15.28, and 15.29).

|

|

|

|

|

Healing

Corner Fracture This

radiograph shows a healing metaphyseal corner fracture of the

proximal tibia, sometimes referred to as a bucket-handle fracture.

Arrows point to the impressive periosteal elevation, causing the

bucket-handle appearance. This fracture is most often seen in

children who have been the victims of child abuse, the result of

shaking or pulling. (Courtesy of Alan E. Oestreich, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Healing

Corner Fracture Periosteal

reaction (arrow) of the distal tibia from a corner fracture.

(Courtesy of Alan E. Oestreich, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spiral

Femur and Proximal Tibia Fracture

This radiograph shows a displaced spiral femur fracture with faint

callus formation. The age of the fracture is just over 10 days. There

is also periosteal reaction of the proximal tibia, which is more

solid and therefore older than the femur fracture. Spiral femur

fractures are caused by trauma that includes a twisting, rotational

force to the bone. Accidental falls can result in spiral fractures if

the child's foot is fixed while his or her body is rotating. Spiral

fractures from abuse are often caused by an angry adult who twists

the leg of the child. The radiographic finding in this photograph is

almost certainly indicative of child abuse because there are two

injuries which occurred at different times and no treatment was

obtained when the injuries occurred. (Courtesy of Alan E. Oestreich,

MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Healing

Fracture of the Distal Humerus

The periosteal reaction along the distal humerus dates this fracture

as older than 10 days. No treatment was obtained for the acute

injury. (Courtesy of Alan E. Oestreich, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Multiple

Healing Rib Fractures There

are healing rib fractures of the right posterior fifth, sixth, and

seventh ribs, the right lateral sixth rib, the left posterior fourth

rib, and the right proximal humerus. The surrounding callus indicates

the fractures are older than 10 days. Rib fractures must always raise

a suspicion of child abuse since accidental rib fractures are

unusual. Rib fractures are usually due to very firm squeezing and may

be seen with shaken baby syndrome. Normal handling of infants or

playful activities do not cause rib fractures. (Courtesy of Alan E.

Oestreich, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Compression

Fracture The wedging of T-12 (arrow)

and probably L-1 indicates vertebral compression fractures. These

fractures are the result of significant forces applied to the spinal

column and are often indicative of child abuse. (Courtesy of Alan E.

Oestreich, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Bucket-Handle"

Fracture Metaphyseal fractures

may appear as in this photograph. When captured at this angle, the

fracture is frequently described as a bucket-handle fracture.

(Courtesy of Michael P. Poirier, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Normal pediatric radiographic

variants, periosteal changes caused by conditions other than healing

fractures, and illnesses that cause fragile bones may all be mistaken for

fractures due to child abuse. A pediatric radiologist should be consulted

if any doubt exists about the radiographic interpretation. Specific

disorders that can be mistaken for child abuse include osteogenesis

imperfecta, copper deficiency, osteopetrosis, rickets, scurvy,

hypervitaminosis A, osteomyelitis, tumors, leukemia, prostaglandin E

overdose, and Caffey's infantile cortical hyperostosis.

Conditions that cause

"brittle bones" must be considered when unexpected fractures

are discovered, even though such cases are rare. The most frequently

discussed brittle bone disorder is osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), a rare

inherited connective-tissue disorder. Associated features seen in some

children with OI include blue sclerae, wormian bones (seen on the skull

x-ray), and osteopenia. A family history of bone fragility, hearing loss,

and short stature is often present. In rare instances, children with OI

lack these associated features.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

If abuse is suspected in a child

under 2 or 3 years of age, obtain a skeletal survey. The skeletal survey

should include a minimum of 19 films (Table 15.1), including frontal

views of the appendicular skeleton and frontal and lateral views of the

axial skeleton. Coned down views over a joint may be needed for best

visualization of metaphyseal injuries. Oblique views are useful for hand,

rib, and nondisplaced lone bone-shaft fractures. All images obtained

(including those of the chest) should use bone technique. Ideally, all studies

should be read by a radiologist while the patient is still in the ED.

Consider computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the head in

infants with skull fractures when abuse is suspected. Suspected abuse

must be reported immediately to the appropriate child protection agency.

Fractures should be managed appropriately.

|

Table 15.1 Skeletal Survey for

Suspected Child Abuse

|

|

|

AP skull

|

|

Lateral

skull

|

|

Lateral

cervical spine

|

|

AP thorax

|

|

Lateral

thorax

|

|

AP pelvis

|

|

Lateral

lumbar spine

|

|

AP humeri (2)a

|

|

AP

forearms (2)a

|

|

Oblique

hands (15°–20°) (2)a

|

|

AP femurs

(2)a

|

|

AP tibias

(2)a

|

|

AP feet

(2)a

|

|

|

a Each a separate exposure: can be combined on one

film.

Source: Courtesy of Paul Kleinman, MD.

|

Clinical Pearls

1. Suspect abuse when a child

has multiple fractures, fractures of different ages, unsuspected (occult)

fractures, or fractures without a consistent trauma history.

2. Accidental trauma that

includes rotational forces can result in a spiral fracture.

3. Obtain a skeletal survey in any

child under 2 years of age who has injuries suspicious of abuse.

4. Radiographic signs of

healing are typically first seen 10 days after a fracture.

5. Fractures that are not

immobilized have a larger callus than immobilized fractures.

|

|

Shaken Baby Syndrome

Associated Clinical Features

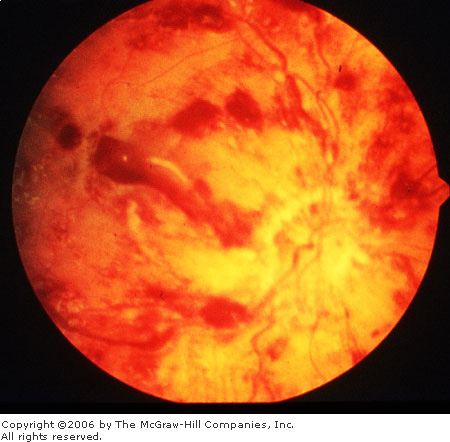

Infants who are violently shaken

may suffer intracranial injury, commonly referred to as "shaken baby

syndrome." Typically, the infant is held by the chest and violently

shaken back and forth. This shaking results in subdural hemorrhages and

cerebral contusions (Figs. 15-30, 15-31, and 15-32). Most of the victims

are under 1 year of age. Some investigators believe that shaking alone is

insufficient to cause these injuries and that therefore some blunt head

trauma must also occur. The name "shaken impact syndrome" has

been suggested to include this mechanism. There are usually no external

signs of trauma, although infants who are shaken may also have fractures,

abdominal trauma, bruises, and other injuries. Neurologic symptoms such

as apnea, seizures, irritability, or altered mental status are commonly

seen but may be absent. Retinal hemorrhages (Figs. 15.33, 15.34) are seen

in 80% of shaken babies. The hemorrhages may be unilateral or bilateral.

Shaken baby syndrome should be strongly considered when retinal

hemorrhages are found in any child under 2 years of age.

|

|

|

|

|

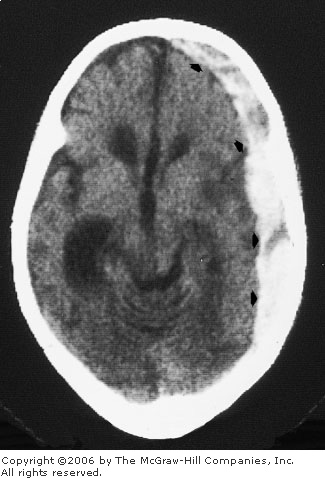

Acute

Subdural Hematoma There is a

crescent-shaped, hyperdense collection, indicating an acute subdural

hematoma over the left cerebral hemisphere (arrows). In

addition, the brain demonstrates chronic injury from a previous

insult, which left the child severely impaired. (Courtesy of William

S. Ball, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

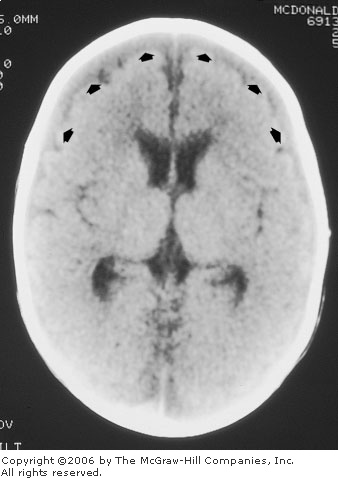

Subacute

Brain Injury from Shaken Baby Syndrome This noncontrast computed tomography scan

demonstrates bilateral subdural collections over the frontal

convexity (arrows). (Courtesy of William S. Ball, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Old

Brain Injury from Shaken Baby Syndrome Three months later there is evidence of

diffuse cerebral volume loss with multifocal areas of increased

density (arrows), representing diffuse cortical and

subcortical injury. (Courtesy of William S. Ball, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Retinal

Hemorrhage Multiple retinal

hemorrhages are present. (Courtesy of Rees W. Shepherd, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Retinal

Hemorrhages Multiple discreet

subhyaloid hemorrhages seen on funduscopic examination in an infant

with shaken baby syndrome. (Courtesy of John D. Baker, MD, and Massie

Research Laboratories, Inc.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Shaken baby syndrome is the most

common cause of intracranial injury in infants. Relatively minor trauma,

such as a fall off a couch or bed, should not cause intracranial damage

unless there are predisposing conditions such as a bleeding disorder or a

preexisting intracranial vascular disorder. Retinal hemorrhages in

association with intracranial trauma is almost always indicative of

shaken baby syndrome.

Findings on computed tomography

(CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that may mimic SBS include

benign extraoral fluid collections, glutaric aciduria type, ruptured

aneurysm, or arteriovenous malformation.

Retinal hemorrhages may be caused

by birth trauma, blunt eye trauma, meningitis, severe hypertension,

sepsis, and coagulopathies. The hemorrhages that result from birth

usually resolve within 3 weeks. There have been reports of

cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) causing retinal hemorrhages. Retinal

hemorrhages from CPR and mechanisms other than major trauma are typically

less extensive than those seen in SBS.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

CT or MRI of the head should be

obtained and the patient treated in the usual fashion. A report of

suspected child abuse must be made to the child protective agency. A

skeletal survey should also be obtained and other injuries noted (Fig.

15.35). An ophthalmologist should follow the patient's retinal injuries.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bruises This child was a victim of shaken baby

syndrome (SBS). Unlike most victims of SBS, he also has signs of

cutaneous injury. Bruises on his right pinna (A) and left upper arm

(B) were noted on examination. (Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

Clinical Pearls

1. Child abuse should be

suspected in any infant with retinal hemorrhages or facial bruising.

2. Infants with SBS may have no

external signs of trauma and minimal neurologic deficits.

3. When retinal hemorrhages are

present, an ophthalmologist should be consulted to assist with the

differential diagnosis and for medicolegal documentation.

4. SBS is most common in

children under 1 year of age.

|

|

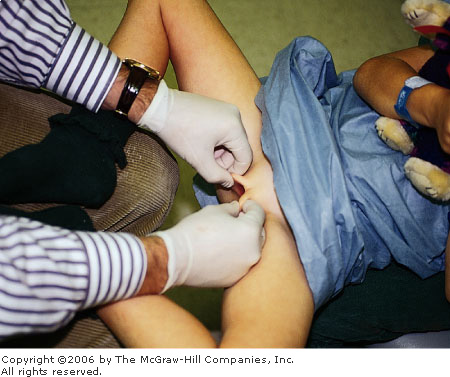

Examination Techniques and Normal Findings

Associated Clinical Features

The genital examination of

prepubertal girls is usually limited to inspection of the external

genitalia and hymen for injury and infection. An internal inspection is

rarely required. Children should first be examined in the

"frog-leg" position. The child can lie on the examination table

or sit on a parent's lap (Fig. 15.36), whichever makes her most

comfortable. Position the patient in a supine position with her knees

flexed and out. The soles of her feet should be opposed (Fig. 15.36).

Alternatively, the child can be placed in a knee-chest position. The

knee-chest position is particularly useful to visualize foreign bodies in

the vagina as well as the posterior vaginal rim.

|

|

|

|

|

Child

Sitting in Mother's Lap for Genital Examination This young girl is being examined while she

sits in her mother's lap. Many young children are less fearful of the

examination if they are held by a parent during the examination. Her

legs are held in the "frog-leg" position as labial traction

is applied. (Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

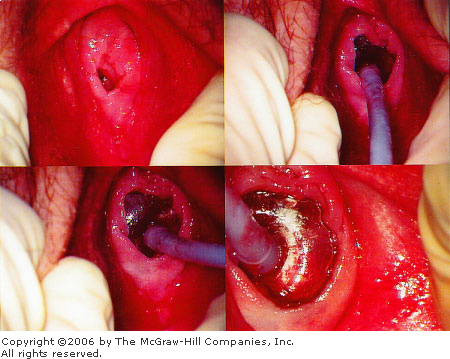

First, examine the perineum for trauma, condylomata,

herpetic lesions, or discharge. Next examine the hymen. To visualize the

hymen, hold the labia majora between the thumb and index fingers of each

hand. Apply lateral and posterior traction to the labia while pulling

them outward (Fig. 15.37). When done properly, this procedure is not

painful and provides excellent visualization of the hymen (Figs. 15-38,

15-39, and 15-40). If the hymen cannot be visualized in the supine

frog-leg position, the knee-chest position should be attempted (Fig.

15.41). Examine the hymen for indications of trauma, such as swelling,

ecchymoses or tears. In pubertal girls, a Foley catheter can help the

examiner inspect the edges of the hymen for injury (Fig. 15.42). To

perform this procedure, insert the deflated catheter into the vagina and

inflate the catheter balloon with 10 mL of saline. Gentle traction can

then be placed on the catheter by pulling until the balloon expands the

hymenal edges. By moving the inflated balloon from side to side to

different sections of the hymen can be exposed.

|

|

|

|

|

Labial

Traction Examination Techniques

Hymenal inspection in prepubertal girls is best accomplished in the

supine position when lateral (1) and posterior (2) traction to the

labia is applied as shown here. (Adapted from Giandino AP et al: A

Practical Guide to the Evaluation of Sexual Abuse in the Prepubertal

Child. Sage Publications, 1992.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

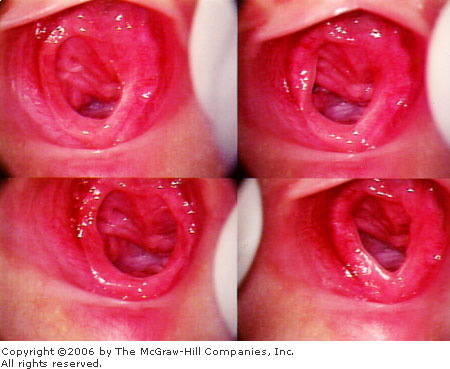

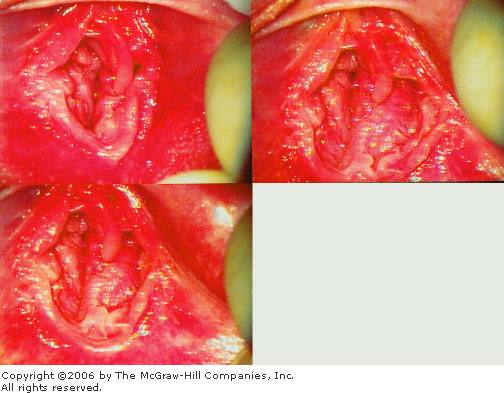

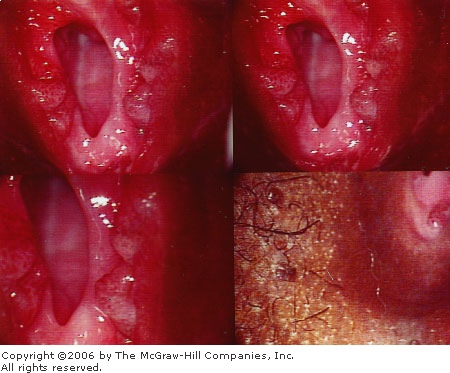

Effect

of Labial Traction on the Appearance of the Prepubertal Introitus These photographs demonstrate how the

appearance of the introitus changes using different examination

techniques in a prepubertal girl. Each photograph shows the introitus

of the same child as different types of labial traction are used. A.

Bottom right: Lateral labial traction only. The hymenal introitus

is closed and the hymenal margins cannot be visualized. B. Bottom

left: More aggressive lateral traction is applied. The introitus

is now partially visible. C. Top right and left: Lateral,

posterior, and caudal labial traction (as illustrated in 15.37). The

introitus is now clearly seen, and the hymen can be adequately

inspected for signs of injury. (Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

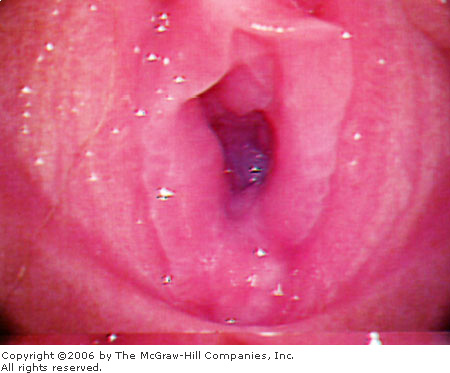

Redundant

Hymenal Tissue These

photographs show the genitalia of the same patient. Because of

redundant hymenal tissue, the introitus appears asymmetric in the top

two photos as well as the bottom left. The text describes methods to

handle redundant hymen. When the hymen is no longer adherent to

itself, the introitus appears symmetric and normal. (Courtesy of

Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Normal

Pubertal Hymen The hymen is

thicker and more redundant in this pubertal child compared to a

prepubertal hymen. This redundancy is due to the effects of estrogen

and begins during puberty. The hymen at 6 o'clock is not adequately

documented by this photograph. Additional

examinations—discussed in the above text—should be used

to visualize the posterior hymen. (Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro,

MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Supine

and Prone Examination Image

(A) of this examination was obtained while the child was supine. The

posterior hymen at 6 o'clock appears to be very narrow. When the

child was examined in the prone (knee-chest) position (B), the 6

o'clock area, now at the top of the photo, is better seen and is

completely normal in appearance. (Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Foley

Catheter Technique A Foley

catheter inserted into the vaginal subsequently filled with 10 cc

saline is used to inspect the hymenal edges for injury. Gentle

traction and movement of the inflated balloon from side to side

exposes different sections of the hymen. The hymen shown in these

photographs is normal. (Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

Techniques

Supine or "frog-leg"

position:

1. The child can lie on an

examination table or, if more comfortable, can sit on her parent's lap.

2. Position the child in a

supine position with her knees out and soles together.

3. Apply traction, as

demonstrated in Fig. 15.38.

Prone or knee-chest position:

1. On the examination table,

position the child on her hands and knees. Her knees should be spread

wider than her shoulders.

2. Have the child rest her

chest to the examination table.

3. Maintain the knee placement

with a swayed backbone.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

If sexual abuse is suspected, a

report of alleged sexual abuse must be made to the child protective

agency. Suspicious or abnormal examination findings should be documented.

The child should be referred for a definitive examination by an expert in

child abuse.

Clinical Pearls

1. Allow the child to sit on

her mother's lap during the examination if this makes her more

cooperative and less afraid.

2. Speculum examinations are

rarely indicated in prepubertal girls and are reserved for removal of an

intravaginal foreign body or evaluation of intravaginal trauma. General

anesthesia is often required before inserting a speculum into a

prepubertal child.

3. Apply caudal traction to the

labia during examination to prevent a superficial tear of the posterior

fourchette.

4. If a portion of the hymen

cannot be visualized because it is adherent to the adjacent labia or to

itself, gently touch the adherent tissue with the contralateral labia to

pull it free. A drop of saline placed onto the posterior hymen may also

separate adherent tissues without causing discomfort to the child.

5. The inner hymenal ring is

usually smooth and uninterrupted. Notches at 3 and 9 o'clock are normal.

6. The shape and appearance of

the normal prepubertal hymen is variable. Annular (Fig. 15.43) and crescentic

(Fig. 15.44) configurations are the most common. Normal hymens may also

be septate (Fig. 15.45), imperforate (no central opening), or cribriform

(multiple small openings).

7. A normal examination does

not exclude sexual abuse. The majority of abused prepubertal girls have

normal genital examinations. Examination findings specific for sexual

abuse are found in approximately 10 to 20% of girls who allege abuse.

|

|

|

|

|

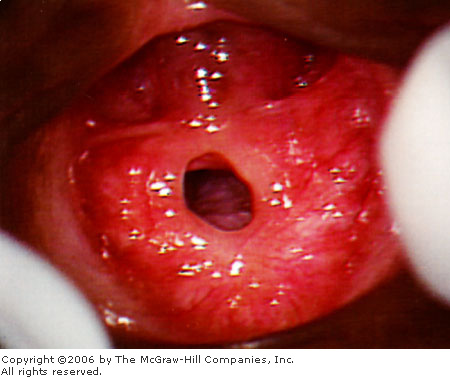

Normal

Annular Hymen The hymen in

this prepubertal girl is annular in shape, extending completely

around the vaginal opening. The inner hymenal ring (introitus) is

smooth and free of any defects, such as lacerations or scars. The

color of the hymen is more deeply red than seen in pubertal women and

does not necessarily indicate infection or trauma. (Courtesy of

Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

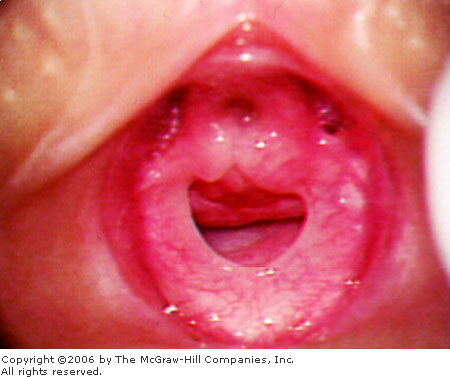

Normal

Crescentic Hymen The hymen in

this prepubertal girl extends from 2 to 10 o'clock and is absent

beneath the urethra between 10 and 2 o'clock. This annular shape is

very common and should not be mistaken for trauma or rupture of the

superior (2 to 10 o'clock) section. The inner hymenal ring (the

introitus) is smooth and free of any defects, such as lacerations or

scars. (Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

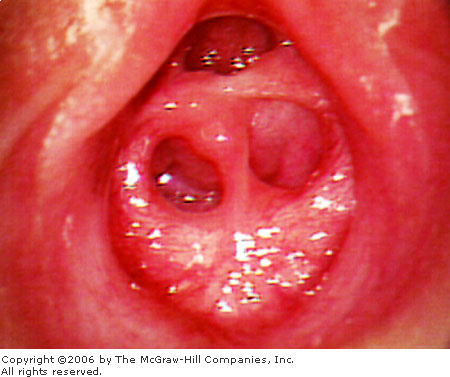

Normal

Septate Hymen This prepubertal

girl has a septum in the center of her introitus. Hymenal septa are

rarely seen after puberty. (Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

Injuries and Findings Due to Sexual Abuse

Associated Clinical Features

Sexual abuse must be considered

in any child with a genital or rectal injury, a sexually transmitted

infection, a history of alleged abuse, or symptoms or behaviors seen in

abused children.

Acute injuries include

lacerations, bruises, abrasions and swelling (Figs. 15-46, 15-47, 15-48,

and 15-49). Acute injuries heal quickly, often within a few days to a

week. Nonacute findings of trauma secondary to sexual abuse can be more

difficult to recognize and should be considered by a child abuse expert.

Nonacute findings include scars, absent hymen, abnormal clefts (Fig.

15.50), and anal changes. Accurate interpretation of genital findings is

dependent on examination technique (see preceding section for suggestions

on examination technique).

|

|

|

|

|

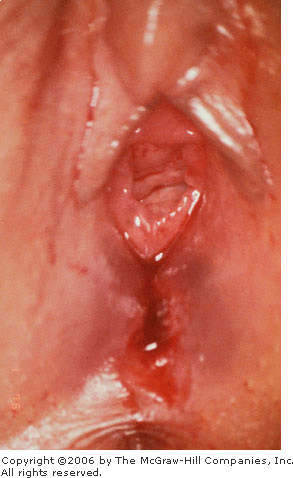

Hymenal

Injury Healed injuries to the

vaginal introitus have caused significant distortion of the anatomy.

The vaginal opening is gaping revealing multiple vaginal rugae. Only

small remnants of the hymen remain.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

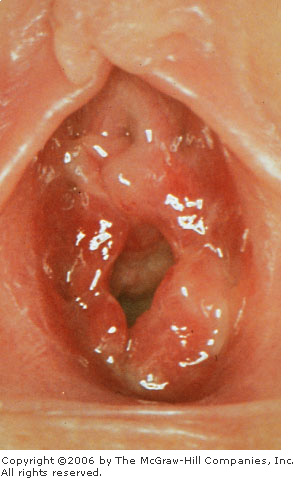

Hymenal

Laceration An acute laceration

with bruising of the posterior fourchette. The nearby hymen is

edematous and ecchymotic. This injury is most likely less than 72 h

old. Injuries to the hymen and posterior fourchette are usually

indicative of sexual assault. Forensic specimens should be collected

after acute sexual assault when the history or examination findings

suggest that semen, saliva, hair, or blood from the perpetrator might

be recovered from the victim. (Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

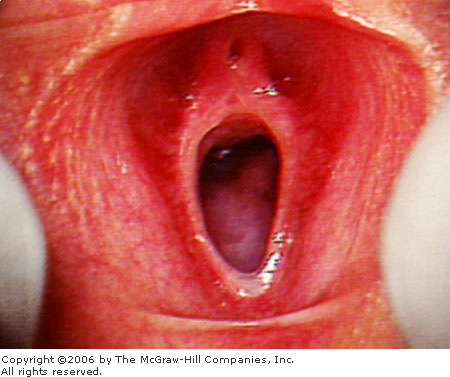

Acute

Rectal Trauma An acute rectal

injury is visible at 12 o'clock. The perianal skin may normally be

darker, with red or blue coloration, than the surrounding skin.

(Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

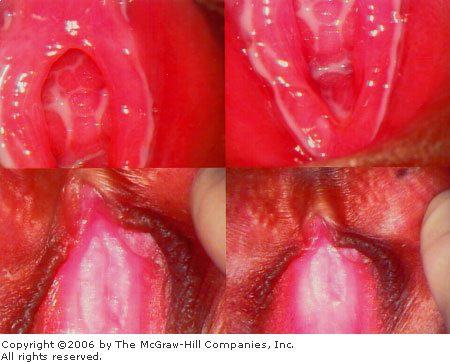

Acute

Hymenal Trauma There is a deep

laceration of the hymen at 7 o'clock and ecchymosis of the hymen at 6

o'clock after recent sexual assault. (Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro,

MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gaping

Introitus, Absent Hymen The

hymen is almost totally absent in this prepubertal girl. There may be

a slight rim of hymen at 6 o'clock. The hymen in young girls is often

very thin and may be totally destroyed after vaginal penetration.

(Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

Sexually transmitted infections diagnosed in a young

person may indicate sexual abuse (Fig. 15.51). Children infected with Neisseria

gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Trichomonas, and syphilis (Fig.

15.52) who did not become infected through perinatal transmission have

almost certainly been infected through sexual contact. Condylomata

acuminata (genital warts) (Fig. 15.53) and herpes simplex may be

transmitted through sexual or nonsexual contact, so that sexual abuse as

well as other mechanisms should be considered.

|

|

|

|

|

Vaginal

Discharge Copious white

discharge is present in this photograph. Vaginal discharge in a

prepubertal child may be an indication of an STD. All children with

vaginal discharge should be cultured for N. gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia.

(Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perirectal

Condyloma Lata (Secondary Syphilis) Perirectal condyloma lata are visible around the rectum.

(Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

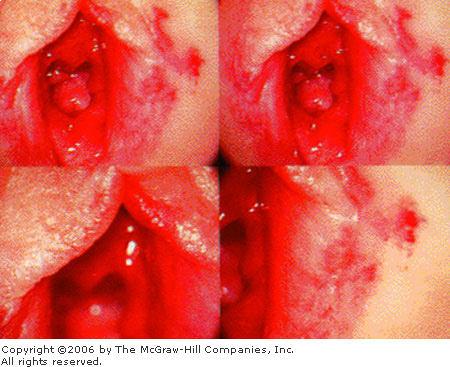

|

|

Perirectal

Condylomata Acuminata (Warts)

Multiple perianal (A) and perihymenal (B) condyloma acuminata are

visible in these photographs. Both individual and multidigitate

lesions are seen. The hymen appears to be normal. (Courtesy of

Charles J. Schubert, MD.)

|

|

All children who allege sexual

abuse should be evaluated, treated, and protected from the alleged

perpetrator. Because of threats by family members or the perpetrator, it

is not unusual for a child to recant initial allegations of sexual abuse.

Although uncommon, some children falsely allege sexual abuse. The

determination of whether allegations are false or of the significance of

recantation should be made by the child protective services worker or by

law enforcement, not by the emergency physician.

Behaviors or symptoms of abuse

are frequently absent at the time of diagnosis but can include fear or

avoidance of an individual, genital or rectal pain, sleep disorders,

regression, enuresis, encopresis, sexual acting out or promiscuity,

depression, declining in school performance, and perpetration of sexual

abuse on younger victims.

Differential Diagnosis

Injury to the hymen from an event

other than sexual abuse is possible though unusual. Masturbation and

self-exploration do not cause vaginal injury in the vast majority of

children. Subtle findings of hymenal trauma are difficult to recognize.

Normal hymenal anatomy may be misdiagnosed as trauma by inexperienced

examiners. Other genital findings mistaken for sexual abuse are listed in

the next section.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Report suspected or alleged

sexual abuse to the appropriate child protection agency. Clearly document

all examination findings. If injuries require repair, appropriate

consultation with surgery or gynecology should be made. Culture for

sexually transmitted infections if there is a vaginal or urethral

discharge. If the history of abuse suggests a risk for infection, obtain

cultures from the genitalia, rectum, and pharynx. Consider syphilis and

HIV testing. Obtain forensic specimens if the alleged abuse occurred

within the previous 72 h and the examination findings or history suggests

that blood, semen, saliva, or hair of the perpetrator might be found on

the victim's body. Offer sexually transmitted disease (STD) and pregnancy

prophylaxes when indicated. Make discharge plans in consultation with the

child protection worker so that the child is not returned to the abusive

environment.

Clinical Pearls

1. It is not necessary to

measure the vaginal opening of prepubertal girls. The size of the

introitus is dependent on examination technique, degree of patient

relaxation, patient age, and other variables. There is no consensus on

normal introitus size among experts.

2. Hymenal notches at 3 and 9

o'clock can be a normal finding.

3. Changes to the posterior

hymen, such as narrowing and notching, may be indicative of penetrating

injury.

4. Rectal abuse often results

in no visible trauma. When trauma does occur, healing may be complete

within 1 to 2 weeks, leaving no visible indication of the injury.

5. The external anus is darker

in color than the rest of the skin and should not be mistaken for

erythema from abuse or infection.

6. Consider sexual abuse when

significant anal fissures are present on examination.

7. Condyloma lata (syphilis)

can be mistaken for condylomata acuminata (warts).

8. Vaginal discharge in a

prepubertal child should always be cultured for Neisseria gonorrhoeae

and Chlamydia.

9. When nits are observed in

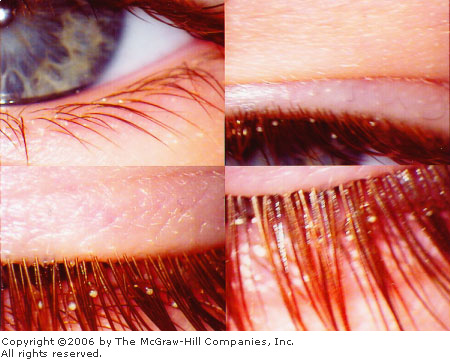

the eyelashes of children (Fig. 15.54), the infecting louse is the pubic

louse. The mode of transmission must be sought and sexual abuse must be

suspected.

|

|

|

|

|

Nits

Nits (the larval form of the

louse) from Phthirus pubis are seen firmly adherent to the

eyelashes in this child. Sexual abuse should be considered. (Courtesy

of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

|

|

Straddle Injury

Associated Clinical Features

Straddle injuries are a frequent

cause of genital trauma and most often result in unilateral abrasions,

bruising, and hematomas of the labia majora and clitoral hood (Fig.

15.55). A clear history describing the straddle injury should be given by

the caretaker.

|

|

|

|

|

Straddle

Injury Laceration of the

clitoral hood due to a fall onto the bar of a bicycle. (Courtesy of

Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Sexual abuse must be considered

in all children with genital injuries. Injuries involving the hymen are

not typical of straddle injuries and are usually the result of sexual

abuse or assault.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Check for urethral injury. Sitz

baths and Polysporin ointment promote healing and minimize discomfort. If

the child has difficulty voiding, she should be encouraged to void in a

bath of warm water.

Clinical Pearls

1. Straddle injuries usually

present with a clear mechanism of injury and a physical examination that supports

the history.

2. Straddle injuries do not

typically involve the hymen or internal vaginal mucosa.

|

|

Labial Adhesions

Associated Clinical Features

Adhesions of the labia minora

occur in young girls and may persist until puberty. A thin translucent line

is seen where the labia meet (Fig. 15.56). The extent of the adhesions

varies from child to child. Involvement is often limited to the posterior

portion of the labia, but some children have more extensive adhesions

completely obscuring the introitus. It is postulated that vulvar

irritation and poor hygiene contribute to the etiology of labial

adhesions.

|

|

|

|

|

Labial

Adhesions Labial adhesions

obscure the hymen in this prepubertal girl. (Courtesy of Robert A.

Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

The hymen and introitus may be

obscured by the adhesions. If the adhesions are unrecognized, a diagnosis

of hymenal trauma and "gaping" introitus may be incorrectly

made. Adhesions may be mistaken for vaginal scars.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Estrogen cream (Premarin) can be

prescribed and applied gently over the adhesions twice daily for 2 to 4

weeks. Recurrence is not uncommon.

Clinical Pearls

1. Adhesions may be congenital

or acquired.

2. It is postulated that vulvar

irritation from sexual abuse may cause labial adhesions, but clear

supporting evidence is lacking.

|

|

Urethral Prolapse

Associated Clinical Features

Prepubertal girls with urethral

prolapse present with vaginal bleeding, vaginal mass, or urinary

complaints. On examination, an annular, erythematous vaginal mass is seen

(Fig. 15.57). Upon close examination, the mass can be seen to originate from

the urethra. If necrotic, the mass is friable.

|

|

|

|

|

Urethral

Prolapse A round

reddish-purple mass is seen in this child's introitus. Careful

examination reveals that the mass originates from the urethra.

(Courtesy of Michael P. Poirier, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Urethral prolapse may be mistaken

for vaginal injury, sexual abuse, or vaginal mass.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The prolapse may resolve within a

few weeks with conservative medical management consisting of daily sitz

baths and topical antibiotics. Topical estrogen cream and oral antibiotic

therapy have also been used with some success. Surgical repair is usually

not required but may be indicated if necrosis is present or conservative

management fails.

Clinical Pearls

1. Urethral prolapse often

presents with painless genital bleeding of unknown etiology.

2. Prolapse is more common in

African American girls.

|

|

Toilet Bowl Injury

Associated Clinical Features

Acute bruising to the glans and

corona of the penis can occur if the toilet seat falls onto the penis

during voiding, trapping the penis between the seat and toilet bowl (Fig.

15.58). This injury is not uncommon in boys of about 3 years of age who

are both inexperienced at voiding while standing and are short enough for

this injury to occur.

|

|

|

|

|

Toilet

Bowl Injury This toddler

presented with a straightforward history of the toilet seat falling

onto his penis during voiding. Despite the swelling and ecchymosis,

he was able to void without difficulty. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop,

MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Genital trauma is always

suspicious for sexual abuse. The mechanism of injury may be difficult to

determine if the injury was unwitnessed.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

No specific treatment is needed

unless the child is unable to void. If the child cannot void, a

retrograde urethrogram and urologic consult are indicated.

Clinical Pearl

1. Genital injuries are

suspicious of sexual abuse if no appropriate history of accidental trauma

is given.

|

|

Perianal Streptococcal Infection

Associated Clinical Features

Presenting complaints are often

rectal pain, itching, bleeding, and rash. Symptoms may be present for

months prior to the diagnosis. The child may be constipated because of

stool retention and may have recently been given laxatives because of

these symptoms. Systemic symptoms are absent. The perianal area is

erythematous and tender (Fig. 15.59). The involved area is well

demarcated from the uninfected skin. Anal fissures and bleeding may be

seen.

|

|

|

|

|

Perianal

Streptococcal Infection

Intense erythema around the anus consistent with perianal

streptococcal infection. (Courtesy of Raymond C. Baker, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Sexual abuse is often

misdiagnosed because of the child's complaints of rectal pain and

bleeding and the above findings on examination. This infection can also be

mistaken for poor hygiene, dermatitis, nonspecific irritation, and

constipation.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Culture or obtain direct antigen

studies for group A beta-hemolytic streptococci. Treat with oral

penicillin for 10 days. Substitute erythromycin for patients allergic to

penicillin. Treatment failures should be treated with IM penicillin

and/or oral clindamycin.

Clinical Pearls

1. Direct antigen studies are

sensitive (89%) and specific (100%) for perianal group A streptococcal infection.

2. Examine the pharynx for

streptococcal infection when considering perianal strep infection.

3. Infection is unusual in

children older than 10 years.

|

|

Lichen Sclerosus Atrophicus

Associated Clinical Features

Lichen sclerosus atrophicus (LSA)

is an unusual dermatitis that affects the anogenital area. The diagnosis

should be suspected whenever an area of hypopigmentation in the shape of

an hourglass is seen around the child's anus and genitalia. The

hypopigmented area is caused by small white or yellowish papules which

coalesce into large plaques. The affected skin is atrophic and bleeds

easily after minor trauma. The hemorrhagic form of LSA includes

subepithelial hemorrhagic lesions to the labia and affected skin, which

can be mistaken for traumatic lesions (Fig. 15.60). Children may complain

of pruritus and dysuria.

|

|

|

|

|

Lichen

Sclerosus Atrophicus The perineum

surrounding the vagina has a bruised appearance. Atrophic skin is

also evident. (Courtesy of Robert A. Shapiro, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

The findings of hemorrhage around

the genitalia and rectum are often mistaken for signs of sexual abuse.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Use symptomatic treatment if

needed; 1%hydrocortisone cream can be prescribed. Refer to dermatologist

for treatment.

Clinical Pearl

1. Lichen sclerosus atrophicus

is the most common dermatitis mistaken for sexual abuse.

|

|