|

Note: Large images and

tables on this page may necessitate printing in landscape mode.

Copyright

©2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved.

Emergency

Medicine Atlas > Part 1. Regional

Anatomy > Chapter 3. Funduscopic Findings >

|

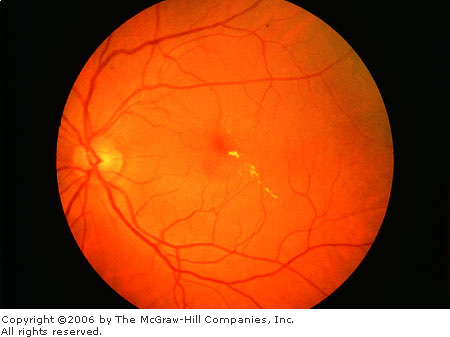

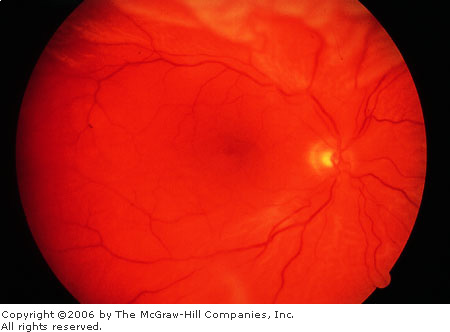

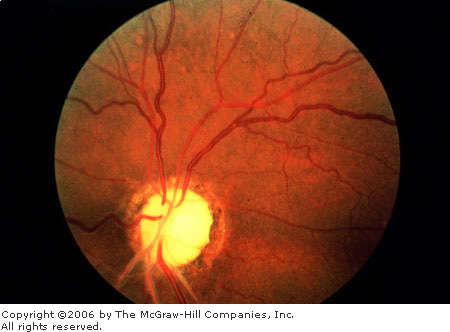

Normal Fundus (Disk, Macular Reflex, Background)

Associated Clinical Features

Disk

The disk is pale pink,

approximately 1.5 mm in diameter, with sharp, flat margins (Fig. 3.1).

The physiologic cup is located within the disk and usually measures less

than six-tenths the disk diameter. The cups should be approximately equal

in both eyes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Normal

Fundus The disk has sharp

margins and is normal in color, with a small central cup. Arterioles

and venules have normal color, sheen, and course. Background is in

normal color. The macula is enclosed by arching temporal vessels. The

fovea is located by a central pit. (Courtesy of Beverly C. Forcier, MD.)

|

|

Vessels

The central retinal artery and

central retinal vein travel within the optic nerve, branching near the

surface into the inferior and superior branches of arterioles and

venules, respectively. Normally the walls of the vessels are not visible;

the column of blood within the walls is visualized. The venules are seen

as branching, dark red lines. The arterioles are seen as bright red

branching lines, approximately two-thirds or three-fourths the diameter

of the venules.

Macula

This is an area of the retina

located temporal to the disk; it is void of capillaries. The fovea is an

area of depression approximately 1.5 mm in diameter (similar to the optic

disk) in the center of the macula. The foveola is a tiny pit located in

the center of the fovea. These areas correspond to central vision.

Background

The background fundus is red;

there is some variation in the color, depending on the amount of

individual pigmentation and the visibility of the choroidal vessels

beneath the retina.

Clinical Pearls

1. Fundal examination should be

an integral part of any eye examination.

2. The cup/disk ratio is

slightly larger in the African-American population.

3. The normal fundus should be

void of any hemorrhages, exudates, or tortuous vasculature.

|

|

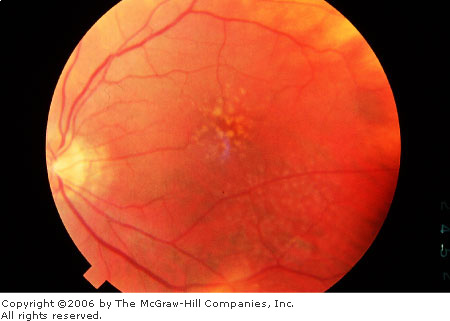

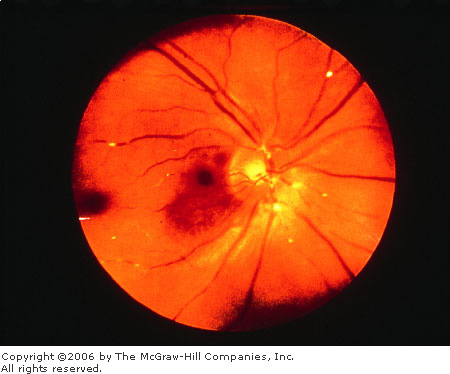

Age-Related Macular Degeneration

Associated Clinical Features

Age-related macular degeneration,

the leading cause of blindness in the elderly, increases in incidence

with each decade over 50. Degeneration of the macula may be evidenced by

accumulation of either drusen (small, discrete, round, punctate nodules),

or soft drusen (larger, pale yellow or gray, without discrete margins

that may be confluent) (Fig. 3.2A and B). Most patients with drusen have

good vision, although there may be decreased visual acuity and distortion

of vision. There may be associated pigmentary changes and atrophy of the

retina. Vision may slowly deteriorate if atrophy occurs.

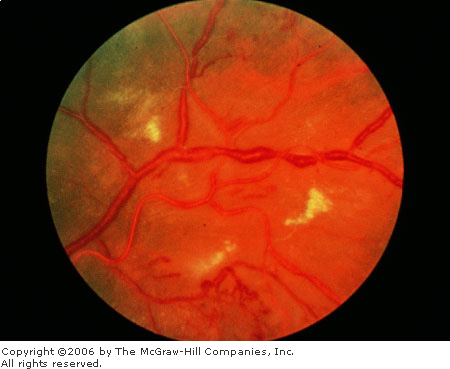

Patients with early or late

degenerative changes of the macula are at risk of developing subretinal

neovascularization (SRNV), which is associated with distortion of vision,

blind spots, and decreased visual acuity. Macular appearance may show

dirty gray lesions, hemorrhage, retinal elevation, and exudation (Fig.

3.3).

|

|

|

|

|

Age-Related

Macular Degeneration, Drusen

Typcial macular drusen and retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) atrophy

(scalloped pigment loss) in age-related macular degeneration.

(Courtesy of Richard E. Wyszynski, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

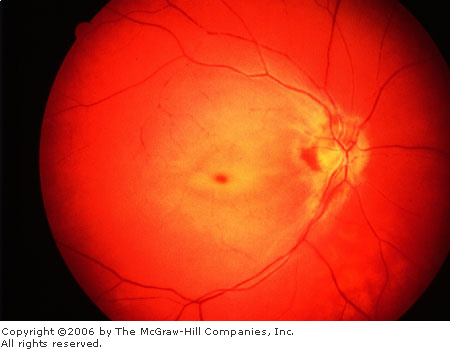

Age-Related

Macular Degeneration, Drusen

Drusen are clustered in the center of the macula. (Courtesy of

Richard E. Wyszynski, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age-Related

Macular Degeneration Hemorrhage

seen beneath the retina in association with subretinal

neovascularization. (Courtesy of Richard E. Wyszynski, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Hereditary macular degenerations,

other acquired macular disorders including toxicities, and retinal

exudation may present similarly.

Hemorrhages and exudates can

present from vascular disease, ocular disorders such as inflammations or

infections, tumors, trauma, and hereditary disorders.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Patients with drusen need ophthalmologic

evaluation every 6 to 12 months or sooner if visual distortion or

decreasing visual acuity develops. If a patient complains of

deterioration of visual acuity or image distortion, prompt ophthalmic

evaluation is warranted, probably including fluorescein angiography. If

SRNV is present, laser treatment may be indicated.

Clinical Pearls

1. Age-related macular

degeneration is the leading cause of blindness in the United States in

patients above 65 years of age.

2. Patient may have normal

peripheral vision.

3. Untreated SRNV can lead to

visual loss within a few days.

4. Patients frequently complain

of distortion with SRNV.

|

|

Exudate

Associated Clinical Features

Hard exudates (Figure 3.4A) are

refractile, yellowish deposits with sharp margins composed of fat-laden

macrophages and serum lipids. Occasionally the lipid deposits form a

partial or complete ring (called a circinate ring) around the leaking

area of pathology. If the lipid leakage is located near the fovea, a

spoke, or star-type distribution of the hard exudates is seen.

Cotton wool spots, or soft

"exudates," are actually microinfarctions of the retinal

nerve-fiber layer, and appear white with soft or fuzzy edges (Fig. 3.4B).

Inflammatory exudates are

secondary to retinal or chorioretinal inflammation.

|

|

|

|

|

Hard

Exudates Linear collection of

yellow lipid deposits with sharp margins in macula. (Courtesy of

Beverly C. Forcier, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cotton

Wool Spots White lesions with

fuzzy margins, seen here approximately one-fifth to one-fourth disk

diameter in size. Orientation of cotton wool spots generally follows

the curvilinear arrangement of the nerve fiber layer. Intraretinal

hemorrhages and intraretinal vascular abnormalities are also present.

(Courtesy of Richard E. Wyszynski, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Hard exudation and cotton wool

spots are associated with vascular diseases such as diabetes mellitus,

hypertension, and collagen vascular diseases but can be seen with

papilledema and other ocular conditions. Inflammatory exudates are seen

in patients with such diseases as sarcoidosis and toxoplasmosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Routine referral for

ophthalmologic and medical workup is appropriate.

Clinical Pearl

1. Hard exudates that are

intraretinal may easily be confused with drusen occurring near Bruch's

membrane, which separates the retina from the choroid.

|

|

Roth's Spot

Associated Clinical Features

Roth's spots are retinal

hemorrhages with a white or yellow center (Fig. 3.5). They are seen in

patients with a host of diseases such as anemia, leukemia, multiple

myeloma, diabetes mellitus, collagen vascular disease, other vascular

disease, intracranial hemorrhage in infants, septic retinitis, and lung

carcinoma.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Roth's

Spot Retinal hemorrhage with

pale center. (Courtesy of William E. Cappaert, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Flamed-shaped or splinter

hemorrhages or dot-blot hemorrhages may resemble Roth's spots.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Routine referral for general

medical evaluation is appropriate.

Clinical Pearls

1. Roth's spots are not

pathognomonic for any particular disease process and can represent a

variety of clinical conditions.

2. These lesions represent red

blood cells surrounding inflammatory cells.

|

|

Emboli

Associated Clinical Features

Plaques, if present, are often

found at arteriolar bifurcations (Fig. 3.6). Patients may have signs and

symptoms of vascular disease including a "source" of emboli

such as carotid bruits or stenosis, aortic stenosis, aneurysms, or atrial

fibrillation. Amaurosis fugax, a transient loss of vision often described

as a curtain of darkness obscuring vision with sight restoration within a

few minutes, may be present in the history.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Emboli Refractile cholesterol plaques usually lodge

at vessel bifurcations. (Courtesy of William E. Cappaert, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Cholesterol emboli (Hollenhorst

plaques), associated with generalized atherosclerosis often from carotid

atheroma, are bright, highly refractile plaques; platelet emboli (carotid

artery or cardiac thrombus) are white and very difficult to visualize;

and calcific emboli (cardiac valvular disease) are irregular and white or

dull gray and much less refractile.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Referral for routine general

medical evaluation is appropriate unless the patient presents with signs

or symptoms consistent with showering of emboli, transient ischemic

attack, or cerebrovascular accident, in which case referral for admission

is indicated.

Clinical Pearls

1. Retinal emboli may produce a

loss of vision, either transient or permanent in nature.

2. Arteriolar occlusion may

occur either in a central or peripheral branch location.

|

|

Central Retinal Artery Occlusion (CRAO)

Associated Clinical Features

The typical patient experiences a

sudden, painless monocular loss of vision, either segmental or complete.

Visual acuity may range from finger counting or light perception to

complete blindness. Fundal findings include: fundal paleness due to

retinal edema; the fovea does not have the edema and thus appears as a

cherry-red spot; the retinal arterioles are narrow and irregular; and the

retinal venules have a "boxcar" appearance (Fig. 3.7).

|

|

|

|

|

Central

Retinal Artery Occlusion The

retinal pallor due to retinal edema is well demonstrated, contrasting

with the "cherry red spot" of the nonedematous fovea. Note

the vascular narrowing and the "boxcar" appearance of the

venules. (Courtesy of Richard E. Wyszynski, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Arteriosclerosis, arterial

hypertension, carotid artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and valvular

heart disease are the most common systemic disorders associated with

central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO). Other associated disorders

include vascular disorders, trauma, and coagulopathies. Temporal

arteritis may present with similar visual complaints.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Attempts to restore retinal blood

flow may be beneficial if performed in a very narrow time window after

the acute event. This may be accomplished by (1) decreasing intraocular

pressure with topical beta-blocker eye drops or intravenous

acetazolamide; (2) ocular massage, applied with cyclic pressure on the

globe for 10 s, followed by release and then repeated. Urgent

consultation with an ophthalmologist if the CRAO is less than a few hours

old is indicated to determine if more aggressive acute therapy

(paracentesis) is warranted. However, such aggressive treatment rarely

alters the poor prognosis. Medical evaluation and treatment of associated

findings may be warranted.

Clinical Pearls

1. History should focus on how

long ago the episode occurred. If the loss of vision occurred recently,

then the patient should be triaged and examined quickly so as to consult

an ophthalmologist within the treatment window.

2. Sudden, painless monocular

vision loss is typical.

3. CRAO may be associated with

temporal arteritis. This diagnosis should be strongly considered in all

patients presenting with signs and symptoms of CRAO who are older than 55

years.

|

|

Central Retinal Vein Occlusion (CRVO)

Associated Clinical Features

Patients are usually older

individuals and complain of sudden, painless visual loss in one eye. The

vision loss is usually not as severe as CRAO and may vary from normal to

hand motion. Funduscopy in a classic, ischemic central retinal vein

occlusion (CRVO) shows a "blood and thunder" fundus:

hemorrhages (including flame, dot or blot, preretinal, and vitreous) and

dilation and tortuosity of the venous system. The arterial system often

shows narrowing. The disk margin may be blurred. Cotton wool spots and

edema may be seen (Fig. 3.8).

|

|

|

|

|

Central

Retinal Vein Occlusion The

amount of hemorrhage is the most striking feature in this photograph.

Also note the blurred disk margin, the dilation and tortuosity of the

venules, and the cotton wool spots. Retinal edema is suggested by

blurring of the retinal details. (Courtesy of Department of

Ophthalmology, Naval Medical Center, Portsmouth, VA.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Retinal detachment, papilledema,

and central retinal artery occlusion can have a similar appearance.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment is rarely effective in

preventing or reversing the damage done by the occlusion and is directed

toward systemic evaluation to identify and treat contributing factors,

hopefully decreasing the chance of contralateral CRVO. Ophthalmologic

evaluation is necessary to confirm the diagnosis, estimate the amount of

ischemia, and follow the patient so as to minimize sequelae of possible

complications such as neovascularization and neovascular glaucoma.

Clinical Pearls

1. Sudden, painless visual loss

in one eye should be evaluated promptly to determine its etiology.

2. Look for the classic

"blood and thunder" funduscopic findings.

3. Consider the differential

diagnosis of acute painful (glaucoma, retrobulbar neuritis) versus

painless vision loss (CRAO, anterior ischemic optic neuropathy,

retinal detachment, subretinal neovascularization, and vitreous

hemorrhage).

|

|

Hypertensive Retinopathy

Associated Clinical Features

Fundus changes that may be seen

with hypertension include generalized and focal narrowing of arterioles,

generalized arteriolar sclerosis (resembling copper or silver wiring),

arteriovenous crossing changes, hemorrhages (usually flame-shaped),

retinal edema and exudation, cotton wool spots, microaneurysms, and disk

edema (Fig. 3.9).

|

|

|

|

|

Hypertension Chronic, severe systemic hypertensive changes

are demonstrated by hard exudates, increased vessel light reflexes,

and sausage-shaped veins. (Courtesy of Richard E. Wyszynski, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Diabetic retinopathy, many

hemopoietic and vascular diseases, traumas, localized ocular pathology,

and papilledema should all be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Medical treatment of

hypertension.

Clinical Pearls

1. Hypertensive arteriolar

findings may be reversible if organic changes have not occurred in the

vessel walls.

2. Always consider hypertensive

retinopathy in the differential diagnosis of papilledema.

|

|

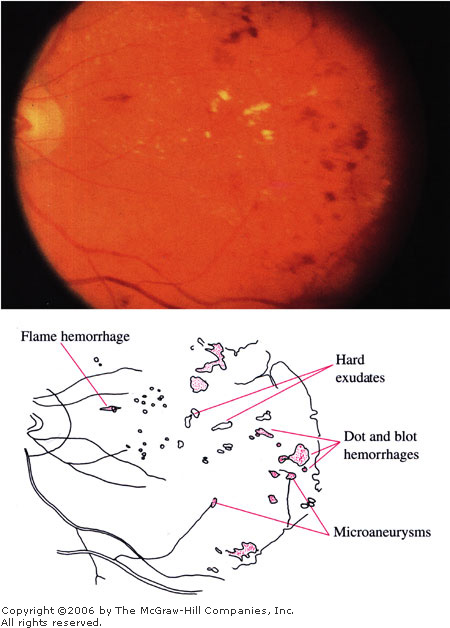

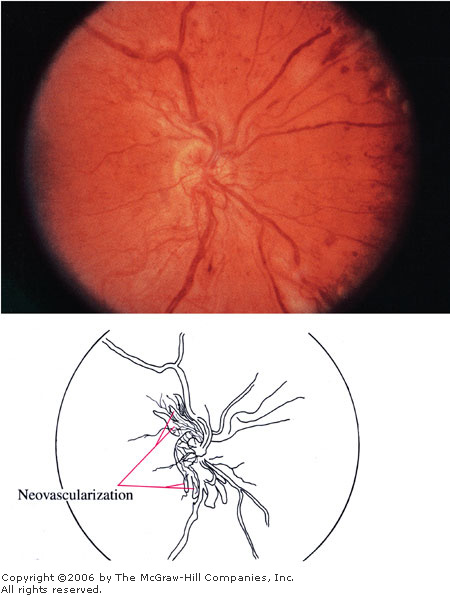

Diabetic Retinopathy

Associated Clinical Features

The early ocular manifestations

of diabetes mellitus are referred to as background diabetic retinopathy

(BDR). Fundus findings include flame or splinter hemorrhages (located in

the superficial nerve fiber layer) or dot and blot hemorrhages (located

deeper in the retina), hard exudates, retinal edema, and microaneurysms

(Fig. 3.10A and B). If these signs are located in the macula, the

patient's visual acuity may be decreased or at risk of becoming

compromised, requiring laser treatment. Preproliferative diabetic

retinopathy can show BDR changes plus cotton wool spots, intraretinal

microvascular abnormalities, and venous beading. Proliferative diabetic

retinopathy is demonstrated by neovascularization at the disk (NVD) or

elsewhere (NVE) (Fig. 3.10C). These require laser therapy owing to risk

of severe visual loss from sequelae: vitreous hemorrhage, tractional

retinal detachment, severe glaucoma.

|

|

|

|

|

Background

Diabetic Retinopathy Hard

exudates, dot hemorrhages, blot hemorrhages, flame hemorrhages, and

microaneurysms are present. Because these changes are located within

the macula, this is classified as diabetic maculopathy. (Courtesy of

Richard E. Wyszynski, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Background

Diabetic Retinopathy An

example of diabetic maculopathy with a typical circinate lipid ring.

(Courtesy of Richard E. Wyszynski, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Proliferative

Diabetic Retinopathy In

addition to the signs seen in background and preproliferative

diabetic retinopathy, neovascularization is seen here coming off the

disk. (Courtesy of Richard E. Wyszynski, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Many vascular and hemopoietic

diseases—such as collagen vascular disease, sickle cell trait,

hypertension, hypotension, anemia, leukemia, inflammatory and infectious

states—and ocular conditions can be associated with some of or all

the above signs.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Routine ophthalmologic referral

for laser or surgical treatment is indicated.

Clinical Pearls

1. Periodic ophthalmologic

evaluations are recommended.

2. Microaneurysms typically

appear 10 years after the initial onset of diabetes, although they may appear

earlier in patients with juvenile diabetes.

3. Control of blood sugar alone

does not prevent the development of vasculopathy.

4. Blurred vision can also

occur from acute increases in serum glucose, causing lens swelling and a

refractive shift even in the absence of retinopathy.

|

|

Vitreous Hemorrhage

Associated Clinical Features

Patients may complain of sudden

loss or deterioration of vision in the affected eye, although bilateral

hemorrhage can occur. The red reflex is diminished or absent, and the retina

is obscured because of the bleeding. Large sheets or three-dimensional

collections of red to red-black blood may be detected (Fig. 3.11A and B).

|

|

|

|

|

Vitreous

Hemorrhage Large amount of

vitreous hemorrhages associated with metallic intraocular foreign

body. The large quantity of blood obscures visualization of retinal

details. (Courtesy of Richard E. Wyszynski, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vitreous

Hemorrhage A smaller amount of

vitreous hemorrhage is more easily photographed. Gravitational effect

on the vitreous blood creates the appearance of a flat meniscus

(keel-shaped blood) in this patient with vitreous hemorrhage

associated with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. (Courtesy of

Richard E. Wyszynski, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Multiple underlying etiologies

include proliferative diabetic retinopathy, retinal or vitreous

detachments, hematologic diseases, trauma (ocular or shaken impact

syndrome), subarachnoid hemorrhage, collagen vascular disease,

infections, macular degeneration, and tumors.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Refer to an ophthalmologist and

an appropriate physician for associated conditions. Ophthalmic

observation, photocoagulation, and surgery are all therapeutic options.

Bed rest may help to increase visualization of the fundus.

Clinical Pearl

1. The patient's vision may

improve somewhat after a period of sitting or standing as the blood

layers out.

|

|

Retinal Detachment

Associated Clinical Features

Patients often complain of

monocular decreased visual function and may describe a shadow or curtain

descending over the eye. Other complaints include cloudy or smoky vision,

floaters, or flashes of light. Central visual acuity is diminished with

macular involvement. Fundal examination may reveal a billowing or

tentlike elevation of retina compared with adjacent areas. The elevated

retina often appears gray. Retinal holes and tears may be seen, but often

the holes, tears, and retinal detachment cannot be seen without indirect

ophthalmoscopy (Fig. 3.12).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Retinal

Detachment A red, flat,

well-focused macula is contrasted with the pale, undulating,

out-of-focus, elevated retina surrounding the macula. (Courtesy of

Richard E. Wyszynski, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Retinal detachments due to retinal

tears or holes can be associated with trauma, previous ocular surgery,

nearsightedness, family history of retinal detachment, and Marfan's

disease. Retinal detachments due to traction on the retina by an

intraocular process can be due to systemic influences in the eye, such as

diabetes mellitus or sickle cell trait. Occasionally retinal detachments

are due to tumors or exudative processes that elevate the retina.

Symptoms of "light flashes" may occur with vitreous changes in

the absence of retinal pathology. Patients may note flashes of light

occurring only in a darkened environment because of the mechanical

stimulation of the retina from the extraocular muscles, usually in a

nearsighted individual.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Urgent ophthalmologic evaluation

and treatment are warranted.

Clinical Pearls

1. Often patients have had

sensation of flashes of light that occur in a certain area of a visual

field in one eye, corresponding to the pathologic pulling on the

corresponding retina.

2. Visual loss may be gradual

or sudden.

|

|

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Retinitis

Associated Clinical Features

Patients may complain of the

gradual onset of the following visual sensations: floaters, scintillating

scotomas (quivering blind spots), decreased peripheral visual field, and

metamorphopsia (wavy distortion of vision). Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

infiltrates appear as focal, small white lesions in the retina that look

like cotton wool spots. CMV is a necrotizing virus that is spread

hematogenously, so that damage is concentrated in the retina adjacent to

the major vessels and the optic disk. Often hemorrhage is involved with

significant retinal necrosis (dirty white with a granular appearance),

giving the "pizza pie" or "cheese and ketchup"

appearance (Fig. 3.13). Optic nerve involvement and retinal detachments

can be present.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CMV

Retinitis "Pizza

pie" or "cheese and ketchup" appearance is

demonstrated by hemorrhages and the dirty, white, granular-appearing

retinal necrosis adjacent to major vessels. (Courtesy of Richard E.

Wyszynski, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

The differential includes other

infections such as toxoplasmosis, other herpesviruses, syphilis, and

occasionally other opportunistic infections.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Reversal, if possible, of

immunosuppression. Ganciclovir and foscarnet have been used with some

effectiveness.

Clinical Pearls

1. HIV retinopathy consists of

scattered retinal hemorrhages and scattered, multiple cotton wool spots

that resolve over time, whereas CMV lesions will typically progress.

2. Although exposure to the CMV

virus is widespread, the virus rarely produces a clinically recognized

disease in nonimmunosuppressed individuals.

|

|

Papilledema

Associated Clinical Features

Papilledema involves swelling of

the optic nerve head, usually in association with elevated intracranial

pressure. The optic disks are hyperemic with blurred disk margins; the

venules are dilated and tortuous. The optic cup may be obscured by the

swollen disk. There may be flame hemorrhages and infarctions (white,

indistinct cotton wool spots) in the nerve fiber layer and edema in the

surrounding retina (Fig. 3.14).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Papilledema Disk is hyperemic and swollen with loss of

sharp margins. The venules are dilated and tortuous. The cup is

obscured. A small flame hemorrhage is seen at 12 to 1 o'clock on the

disk margin. (Courtesy of Department of Ophthalmology, Naval Medical

Center, Portsmouth, VA.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Ocular inflammation (e.g.,

papillitis), tumors or trauma, central retinal artery or vein occlusion,

optic nerve drusen, and marked hyperopia may present with similar

findings.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Expeditious ophthalmologic and

medical evaluation is warranted.

Clinical Pearls

1. The top of a swollen disk

and the surrounding unaffected retina will not both be in focus on the

same setting on direct ophthalmoscopy.

2. Papilledema is a bilateral

process, though it may be slightly asymmetric. A unilateral swollen disk

suggests a localized ocular or orbital process.

3. Vision is usually normal

acutely, though the patient may complain of transient visual changes. The

blind spot is usually enlarged.

4. Diplopia from a sixth

cranial nerve palsy can be associated with increased intracranial

pressure and papilledema.

|

|

Optic Neuritis

Associated Clinical Features

Most cases of optic neuritis are

retrobulbar and involve no changes in the fundus, or optic disk, during

the acute episode. With time, variable optic disk pallor may develop

(Fig. 3.15). Typical retrobulbar optic neuritis presents with sudden or

rapidly progressing monocular vision loss in patients younger than 50

years. There is a central visual field defect that may extend to the

blind spot. There is pain on movement of the globe. The pupillary light

response is diminished in the affected eye. Over time the vision improves

partially or completely; minimal or severe optic atrophy may develop.

Papillitis, inflammation of the intraocular portion of the optic nerve,

will accompany disk swelling, with a few flame hemorrhages and possible

cells in the vitreous.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Optic

Nerve Pallor Optic nerve

pallor, either segmental (top) or generalized (bottom),

is a nonspecific change that may be associated with a previous

episode of optic neuritis or other insults to the optic nerve.

(Courtesy of Richard E. Wyszynski, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Optic neuritis must be

differentiated from papilledema (bilateral disk swelling, typically with

no acute visual loss with the exception of transient visual changes),

ischemic neuropathy (pale, swollen disk in an older individual with sudden

monocular vision loss), tumors, metabolic or endocrine disorders. Most

cases of optic neuritis are of unknown etiology. Some known causes of

optic neuritis include demyelinating disease, infections (including

viral, syphilis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis), or inflammations from

contiguous structures (sinuses, meninges, orbit).

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment is controversial; often

none is recommended. Oral steroids may worsen prognosis in certain cases.

Intravenous steroids may be considered after consultation with an

ophthalmologist.

Clinical Pearls

1. Monocular vision loss with

pain on palpation of the globe or with eye movement are clinical clues to

the diagnosis.

2. Sudden or rapidly

progressing central vision loss is characteristic.

3. Most cases of acute optic

neuritis are retrobulbar. Thus ophthalmoscopy shows a normal fundus.

|

|

Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (AION)

Associated Clinical Features

Anterior ischemic optic

neuropathy (AION) presents with a sudden loss of visual field (often

altitudinal), usually involving fixation, in an older individual. The

loss is usually stable after onset, with no improvement, and only

occasionally, progressive over several days to weeks. Pale disk swelling

is present involving a sector or the full disk, with accompanying flame

hemorrhages (Fig. 3.16).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anterior

Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Pale

disk swelling and flame hemorrhages are present. This patient also

has an unrelated retinal scar due to toxoplasmosis. (Courtesy of

William E. Cappaert, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

The common, nonarteritic causes

of AION (probably arteriosclerosis) need to be differentiated from

arteritic ones, such as giant cell arteritis. If untreated, the latter

will involve the other eye in 75% of cases, often in a few days to weeks.

These elderly individuals often have weight loss, masseter claudication,

weakness, myalgias, elevated sedimentation rate, and painful scalp,

temples, or forehead.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Routine ophthalmologic and

medical evaluation is appropriate.

Clinical Pearls

1. Consider AION in an elderly

patient with sudden, usually painless visual field loss.

2. Rule out giant cell

arteritis. These patients tend to be older (age > 55) and may have associated

CRAO or cranial nerve palsies (III, IV, or VI) with diplopia.

|

|

Glaucoma

Associated Clinical Features

Narrow or closed-angle glaucoma

results from a physical appositional impedance of aqueous humor outflow.

Symptoms range from complaints of colored halos around lights and blurred

vision to severe pain (may be described as a headache or brow ache)

associated with nausea and vomiting. Intraocular pressures are markedly

elevated. Perilimbal vessels are injected, the pupil is middilated and

poorly reactive to light, and the cornea may be hazy and edematous (see

also Chap. 2 for external ocular images).

Two-thirds of glaucoma patients

have open-angle glaucoma due to an abnormality of primary tissues

responsible for the outflow of fluid out of the eye. Often they are

asymptomatic. They may have a family history of glaucoma. Funduscopy may

show asymmetric cupping of the optic nerves (Fig. 3.17). The optic nerve

may show notching, local thinning of tissue, or disk hemorrhage. Optic

cups enlarge, especially vertically, with progressive damage. Tissue loss

is associated with visual field abnormalities, usually in arcuate

patterns. The intraocular pressure is often but not always greater than

21 mmHg.

|

|

|

|

|

Glaucomatous

Cupping The cup is not

central; it is elongated toward the rim superotemporally. (Courtesy

of Department of Ophthalmology, Naval Medical Center, Portsmouth, VA.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Acute Glaucoma

Painful visual loss (retrobulbar

optic neuritis, iritis, endophthalmitis), referred pain from

nonophthalmic source.

Chronic Glaucoma

Normal variants, ocular

conditions like disk drusen or optic neuropathy.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Acute Narrow-Angle Glaucoma

Emergent ophthalmologic

consultation and administration of medications to decrease intraocular

pressure. Beta-blocker drops (timolol), carbonic anhydrase inhibitors

(acetazolamide), cholinergic stimulating drops (pilocarpine),

hyperosmotic agents (osmoglyn), and alpha-adrenergic agonists

(apraclonidine) may be employed prior to laser or surgical iridotomy (see

also Chap. 2).

Open-Angle Glaucoma

Long-term ophthalmic evaluation

and treatment with medications and laser or surgery.

Clinical Pearls

1. A high index of suspicion

must be maintained, since associated complaints such as nausea, vomiting,

and headache may obscure the diagnosis.

2. Open-angle glaucoma usually

causes no symptoms other than gradual loss of vision.

3. Congenital glaucoma is rare.

However, because of prognosis if diagnosis is delayed, consider

congenital glaucoma in infants and children with any of the following:

tearing, photophobia, enlarged eyes, cloudy corneas.

4. Asymmetric cupping, enlarged

cups, and elevated intraocular pressure are hallmarks of open-angle

glaucoma.

|

|

Subhyaloid Hemorrhage in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

(SAH)

Associated Clinical Features

Subhyaloid hemorrhage appears as

extravasated blood beneath the retinal layer (Fig. 3.18). These are often

described as "boat-shaped" hemorrhages to distinguish them from

the "flame-shaped" hemorrhages on the superficial retina. They

may occur as a result of blunt trauma but are perhaps best known as a

marker for subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). In SAH, the hemorrhages appear

as a "puff" of blood emanating from the central disk.

|

|

|

|

|

Subhyaloid

Hemorrhage Subhyaloid

hemorrhage seen on funduscopic examination in a patient with

subarachnoid hemorrhage. (From Edlow and Caplan: Primary care:

Avoiding pitfalls in the diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage. N

Engl J Med 2000; 342:29–36, with permission.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

SAH, shaken impact syndrome,

hypertensive retinopathy, and retinal hemorrhage should all be considered

and aggressively evaluated.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

No specific treatment is required

for subhyaloid hemorrhage. Treatment is dependent on the underlying

etiology. Appropriate specialty referral should be made in all cases.

Clinical Pearl

1. A funduscopic examination

looking for subhyaloid hemorrhage should be included in all patients with

severe headache, unresponsive pediatric patients, or those with altered

mental status.

|

|