|

Note: Large images and

tables on this page may necessitate printing in landscape mode.

Copyright

©2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved.

Emergency

Medicine Atlas > Part 1. Regional

Anatomy > Chapter 4. Ophthalmic Trauma >

|

Corneal Abrasion

Associated Clinical Features

Corneal abrasions are heralded by

the acute onset of eye discomfort accompanied by tearing and a

foreign-body sensation. Conjunctival injection may also be noted. If the

area of abrasion is large or central, visual acuity may be affected.

Large abrasions or delays in seeking care may be accompanied by

photophobia and headache from ciliary muscle spasm. Associated findings

or complications include traumatic iritis, hypopyon, or a corneal ulcer

(described in Chap. 2). Examination before and after instillation of

fluorescein, preferably with a slit lamp, usually reveals the defect

(Figs. 4.1 and 4.2). Fluorescein pools and stains the area where corneal

epithelium has been denuded.

|

|

|

|

|

Corneal

Abrasion Seen under

magnification from the slit lamp, corneal abrasion can sometimes be

appreciated without fluorescein staining. This abrasion is seen

without using the cobalt blue light. (Courtesy of Harold Rivera.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Corneal

Abrasion The same abrasion as

Fig. 4.1 is seen under magnification from the slit lamp with

fluorescein stain using the cobalt blue light. (Courtesy of Harold

Rivera.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Corneal foreign body,

conjunctivitis, conjunctival foreign body, iritis, and corneal ulcer can

present with similar complaints.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Instillation of topical

anesthetic drops permits a better examination and relieves pain. A

short-acting cycloplegic (e.g., cyclopentolate 0.5%, homatropine 5%) may

reduce ciliary spasm and pain and should be considered in patients with

larger abrasions or in those who complain of headache or photophobia.

Topical antibiotic drops or ointment—preferably broad-spectrum

agents such as gentamicin, sulfacetamide, or erythromycin—are used

to prevent secondary bacterial infection. A soft double-layer patch may

also be applied. Neither treatment with topical antibiotics nor patching

has been scientifically validated, and routine use of these practices has

been called into question. Follow-up is required for any patient who is

still symptomatic after 12 h.

Clinical Pearls

1. Only sterile fluorescein

strips should be used, since the corneal epithelium, the primary barrier

to infection, has been potentially disrupted.

2. Mucus may simulate the

fluorescein uptake, but its position changes with blinking.

3. Multiple linear corneal

abrasions, the "ice-rink sign," may result from the adherence

of a foreign body to the conjunctiva under the lid (Fig. 4.3). The lid

should always be everted to rule out a retained foreign body.

4. A high index of suspicion of

a perforating injury should be maintained for any abrasion that occurs as

a result of grinding or striking metal on metal.

5. Fluorescein streaming away

from an "abrasion" (Seidel's test) may be an indication of a

corneal perforation.

|

|

|

|

|

Foreign

Body under the Upper Lid Lid

eversion is an essential part of the eye examination. (Courtesy of

Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

Corneal Foreign Body

Associated Clinical Features

Patients typically give a history

of something in the eye or complain of foreign-body sensation. If the

foreign body overlies the cornea, the patient's vision may be affected.

There may be tearing, conjunctival injection, and ciliary flush (Fig.

4.4). If several hours have elapsed since the occurrence of the injury,

there may be headache and photophobia in addition to the above signs and

symptoms.

|

|

|

|

|

Foreign

Body on the Cornea A foreign

body is lodged at 10 o'clock on the cornea. Note the localized

ciliary flush in the surrounding conjunctiva at the limbus. (Courtesy

of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

The most important consideration

in the differential is the possibility of a penetrating injury to the

globe. A meticulous history about the mechanism of injury (grinding or

metal on metal) must be elicited. Conjunctival foreign body, corneal

abrasion, intraocular foreign body, conjunctivitis, iritis, and glaucoma

should also be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

If superficial, removal of the

foreign body with a moist cotton-tipped applicator may be attempted; if

unsuccessful, an eye spud or small (25-gauge) needle may be used. After

removal, if a residual corneal abrasion is present, instill an antibiotic

solution or ointment. A "short-acting" cycloplegic (e.g.,

cyclopentolate 0.5%) should be considered in patients with complaints of

headache or photophobia. Metallic foreign bodies are often accompanied by

a "rust ring" discoloration of the surrounding corneal

epithelium (Fig. 4.5). Removal of the rust ring can be attempted, either

with a needle or preferably with a small burr drill device available

commercially. Alternatively, the patient may be referred to an

ophthalmologist the following day.

|

|

|

|

|

"Rust

Ring" A rust ring has

formed from a foreign body (likely metallic) in this patient. A burr

drill can be used for attempted removal, which, if unsuccessful, can

be reattempted in 24 h. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Clinical Pearls

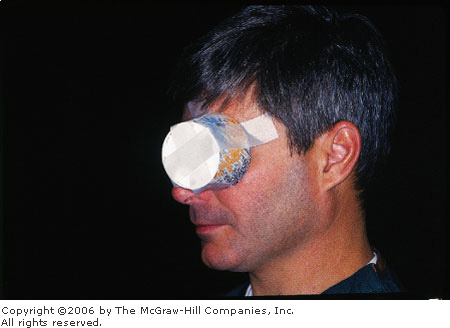

1. Treatment of a suspected

penetrating injury to the globe includes immediate referral, eye rest,

protective patching (Figs. 4.6, 4.7), and elevation of the head of the

bed.

2. If history of ocular

penetration is present, a diligent search for a foreign body is

indicated. X-ray may identify the foreign body (Fig. 4.8), but computed

tomography (CT) is the diagnostic study of choice.

3. Be sure to evert the upper

lid and search carefully for a foreign body. A foreign body adherent to

the upper lid abrades the cornea, producing the "ice-rink"

sign, caused from multiple linear abrasions.

4. If a rust ring is present

from a metallic foreign body, its removal can be attempted, or the

patient may await ophthalmology follow-up in 24 h.

5. Multiple small corneal

foreign bodies (e.g., glass or sand) may be removed by irrigating with

normal saline or tap water. The instillation of a topical anesthetic

facilitates the irrigation process.

|

|

|

|

|

Protective

Metal (Fox) Shield A

protective shield is used in the setting of a suspected or confirmed

perforating injury. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Protective

Shield A protective shield is

readily fashioned from a paper cup if a metal shield is not

available. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intraocular

Foreign Body A metallic

foreign body is seen on a plain radiograph and—with comparison

with a lateral film—indicates the presence of an intraocular

foreign body. (Courtesy of Department of Ophthalmology, Naval Medical

Center, Portsmouth, VA.)

|

|

|

|

Eyelid Laceration

Associated Clinical Features

Eyelid lacerations should always

prompt a thorough search for associated injury to the globe, penetration

of the orbit, or involvement of surrounding structures (e.g., lacrimal

glands, ducts, puncta) (Fig. 4.9). Depending on the mechanism of injury,

a careful exclusion of foreign body may be indicated.

|

|

|

|

|

Eyelid

and Adnexa Anatomy Ocular

trauma should prompt examination of surrounding anatomic structures

for associated injuries.

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Laceration of the levator

palpebrae musculature or tendinous attachments, laceration of the canthal

ligamentous support, division of the lacrimal duct or puncta, and

penetration of the periorbital septum should all be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Eyelid lacerations involving

superficial skin can be repaired with 6-0 nonabsorbable interrupted

sutures, which should remain in place for 3 days. Lacerations through an

anatomic structure called the gray line (see Fig. 4.9), situated on the

palpebral edge, require diligent reapproximation and should be referred.

Other injuries that require specialty consultation for repair include:

—Lacerations through the

lid margins: these require exact realignment to avoid entropion or

extropion.

—Deep lacerations through

the upper lid that divide the levator palpebrae muscles or their

tendinous attachments: these must be repaired with fine absorbable suture

to avoid ptosis.

—Lacrimal duct injuries:

these are repaired by stenting of the duct, otherwise excessive spilling

of tears (epiphora) will result.

—Medial canthal

ligaments: these must be repaired to avoid drooping of the lids.

The most important objectives are

to rule out injury to the globe and to search diligently for foreign

bodies.

Clinical Pearls

1. Lacerations of the medial

one-third of the lid (Fig. 4.10) should always raise suspicion for injury

to the lacrimal ducts or puncta as well as the medial canthal ligament.

2. A small amount of adipose

tissue seen within a laceration is a sign that perforation of the orbital

septum has occurred (since there is no subcutaneous fat in the lids

themselves).

3. Injuries involving the

orbital septum carry a higher than normal risk of globe injury and

intraorbital foreign body as well as a higher risk for orbital

cellulitis. A CT scan and specialty consultation should be considered.

4. Any injury to the lids

involving tissue loss or avulsion should be referred for specialty

consultation.

|

|

|

|

|

Eyelid

Laceration This laceration

involving the medial third of the lid clearly violates the

canalicular structures. The patient was struck by a person wearing a

ring. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

Hyphema

Associated Clinical Features

Injury to the anterior chamber

that disrupts the vasculature supporting the iris or ciliary body results

in a hyphema. The blood tends to layer and because of gravity forms a

meniscus (Fig. 4.11). Symptoms can include pain, photophobia, and

possibly blurred vision secondary to obstructing blood cells. Nausea and

vomiting may signal a rise in intraocular pressure (glaucoma) caused by

blockage of the trabecular meshwork by blood cells or clot.

|

|

|

|

|

Hyphema This hyphema has almost completely layered

while the patient's head was tilted. Note the hazy greenish area at 6

o'clock in contrast to the remainder of the blue iris. This

represents blood circulating in the anterior chamber that has not yet

layered. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Hypopyon (pus within the anterior

chamber), vitreous hemorrhage, iridodialysis, penetrating injury to the

globe, and intraocular foreign body should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Prevention of further hemorrhage

is the first goal. The patient should be kept at rest in the supine

position with the head elevated slightly. A hard eye shield should be

used to prevent further trauma from manipulation. Oral or parenteral pain

medication and sedatives are appropriate, but avoid agents with antiplatelet

activity such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Antiemetics should be used if the patient has nausea. Further treatment

is at the discretion of specialty consultants but may include topical and

oral steroids, antifibrinolytics such as aminocaproic acid, or surgery.

Intraocular pressure (IOP) should be measured in all patients unless

there is a suspicion of penetrating injury to the globe. If elevated, IOP

should be treated with appropriate agents including topical beta

blockers, pilocarpine, and, if needed, osmotic agents (mannitol,

sorbitol) and acetazolamide. The need for admission for small hyphemas is

variable, since some centers admit all whereas others individualize

treatment. Ophthalmologic consultation is warranted to determine local

practices.

Clinical Pearls

1. The patient should be told

specifically not to read or watch television, as these activities result

in greater than usual ocular activity.

2. Depending on the severity of

the initial hyphema, rebleeding may occur in 10 to 25% of patients,

commonly in 2 to 5 days as the original clot retracts and loosens.

3. Blood that is not absorbed

from the anterior chamber may infiltrate and stain the cornea, leaving a

brown discoloration.

4. An "eightball" or

total hyphema occurs when blood fills the entire anterior chamber. These

lesions require surgical evacuation.

5. Patients with sickle cell

and other hemoglobinopathies are at risk for sickling of blood inside the

anterior chamber (Fig. 4.12). This can cause a rise in IOP from physical

obstruction of the trabecular meshwork.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hyphema A small hyphema (about 5%) in a patient with

sickle cell disease. (Courtesy of Dallas E. Peak, MD.)

|

|

|

|

Iridodialysis

Associated Clinical Features

Traumatic iridodialysis is the

result of an injury, typically blunt trauma, that pulls the iris away

from the ciliary body. The resulting deformity appears as a lens-shaped

defect at the outer margin of the iris (Fig. 4.13). Patients may present

complaining of a "second pupil." As the iris pulls away from

the ciliary body, a small amount of bleeding may result. Look closely for

associated traumatic hyphema.

|

|

|

|

|

Traumatic

Iridodialysis The iris has

pulled away from the ciliary body as a result of blunt trauma.

(Courtesy of Department of Ophthalmology, Naval Medical Center,

Portsmouth, VA.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Traumatic hyphema, penetrating

injury to the globe, scleral rupture, intraocular foreign body, and lens

dislocation causing billowing of the iris should all be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

A remote traumatic iridodialysis

requires no specific treatment in the ED. Recent history of ocular trauma

should prompt a diligent slit-lamp examination for associated hyphema or

lens discoloration. If hyphema is present, it should be treated as

discussed (see "Hyphema", above). Pure cases of iridodialysis

may be referred for specialty consultation to exclude other injuries; if

the defect is large enough to result in monocular diplopia, surgical

repair may be necessary.

Clinical Pearls

1. The examination should

carefully exclude posterior chamber pathology and hyphema.

2. A careful review of the

history to exclude penetrating trauma should be made. If the history is

unclear, CT scan may be used to exclude the presence of intraocular

foreign body.

3. A careful examination

includes searching for associated lens dislocation.

|

|

Lens Dislocation

Associated Clinical Features

Lens dislocation may result from

a sudden blow to the globe with resultant stretching of the zonule fibers

that hold the lens in place (Fig. 4.14). The patient may experience

symptoms of monocular diplopia or gross blurring of images, depending on

the severity of the injury. The edge of the subluxed lens may be visible

when the pupil is dilated (Fig. 4.15). If all the zonule fibers tear and

the lens is dislocated, it may lodge in the anterior chamber or the vitreous.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lens

Dislocation Lens dislocation

revealed during slit-lamp examination. Note the zonule fibers, which

normally hold the lens in place. (Courtesy of Department of

Ophthalmology, Naval Medical Center, Portsmouth, VA.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

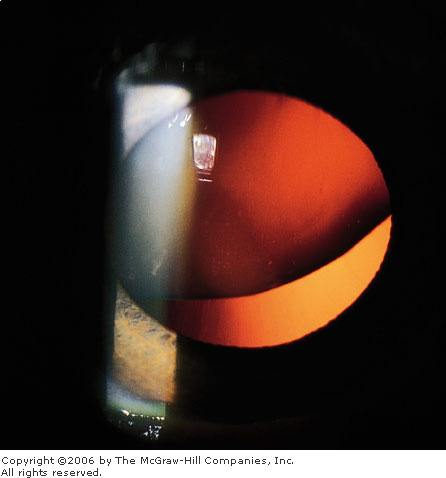

|

|

Lens

Dislocation The edge of this

dislocated lens is visible with the pupil dilated as an altered red

reflex. (Courtesy of Department of Ophthalmology, Naval Medical

Center, Portsmouth, VA.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Marfan's syndrome, tertiary

syphilis, and homocystinuria may be present and should be considered in

patients presenting with lens dislocation.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Almost all cases require surgery

if the lens is totally dislocated; partial subluxations may require only

a change in refraction.

Clinical Pearls

1. Patients may experience lens

dislocation with seemingly trivial trauma if they have an underlying

coloboma of the lens (see Fig. 4.20), Marfan's syndrome, homocystinuria,

or syphilis.

2. Iridodonesis is a trembling

movement of the iris noted after rapid eye movements and is a sign of

occult posterior lens dislocation.

|

|

Open Globe

Associated Clinical Features

Open globe injuries resulting

from penetrating trauma can be subtle and easily overlooked. All are

serious injuries. Signs to look for are loss of anterior chamber depth

caused by leakage of aqueous humor, a teardrop-shaped pupil, or prolapse

of choroid through the wound (Fig. 4.16).

|

|

|

|

|

Open

Globe This injury is not

subtle; extruded ocular contents (vitreous) can be seen; a teardrop

pupil is also present. (Courtesy of Alan B. Storrow, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Iridodialysis, corneal foreign

body, and scleral rupture may have similar presentations.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

All open globe injuries require

specialty consultation. A Fox (metal) eye shield should be placed over

the affected eye. No attempts to examine, measure pressures, or

manipulate the eye should be made. Intravenous antibiotics to cover

gram-positive organisms are appropriate. Sedation and aggressive pain

management are crucial and should be used liberally to prevent or

decrease expulsion of intraocular contents due to crying, activity, or

vomiting. Antiemetics should be given if nausea is present. Tetanus

immunization should be updated. Many open globe injuries are associated

with other significant blunt trauma injuries.

Clinical Pearls

1. When a large foreign body

such as a pencil or nail protrudes from the globe, resist the temptation

to remove it. Such objects should be left in place until definitively

treated in the operating room.

2. Control of pain, activity, and

nausea may be sight-saving and requires proactive use of appropriate

medications.

3. Use of lid hooks, retractors

(Fig. 4.17), or even retractors fashioned from paper clips (Fig. 4.18) is

preferred to open the eyelids of trauma victims with blepharospasm or

massive swelling. Attempts to do this with fingers can inadvertently

increase the pressure on the globe.

4. Penetrating globe injuries

are a relative contraindication to the sole use of depolarizing

neuromuscular blockade (e.g., succinylcholine). Pretreatment with a small

dose of a nondepolarizing agent should be given to abolish the

fasciculations and resultant increased intraocular pressure.

|

|

|

|

|

Eyelid

Retractors Retractors are used

to gain exposure without applying pressure to the globe. (Courtesy of

Dallas E. Peak, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eyelid

Retractors Retractors

fashioned from paper clips can safely be used when standard

retractors are not available. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

Scleral Rupture

Associated Clinical Features

A forceful blow to the eye may

result in a scleral rupture. The diagnosis is obvious when orbital

contents are seen spilling from the globe itself. The diagnosis may be

more occult in situations where only a tiny rent in the sclera has

occurred. When rupture occurs at the limbus, a small amount of iris may

herniate, resulting in an irregularly shaped pupil called a teardrop

pupil (Fig. 4.19). A teardrop pupil may also be the result of a

penetrating foreign body. Mechanism is the key to distinguishing these

two causes. Another associated finding is bloody chemosis of the bulbar

conjunctiva over the area of scleral rupture. This may be distinguished

from a simple subconjunctival hematoma by bulging of the conjunctiva.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Corneal-Scleral

Rupture A teardrop pupil is

present, with a small amount of iris herniating from a rupture at the

limbus. These injuries may initially go unnoticed. (Courtesy of

Dallas E. Peak, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Subconjunctival hematoma,

nontraumatic bloody chemosis, corneal-scleral laceration, intraocular

foreign body, iridodialysis, and traumatic lens dislocation may have a

similar presentation. A coloboma of the iris (Fig. 4.20) may appear

similar to a teardrop pupil.

|

|

|

|

|

Iris

Coloboma Iris coloboma is a

congenital finding resulting from incomplete closure of the fetal

ocular cleft. It appears as a teardrop pupil and may be mistaken for

a sign of scleral rupture. (Courtesy of Department of Ophthalmology,

Naval Medical Center, Portsmouth, VA.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Urgent specialty consultation and

operative management are mandatory. The eye should be protected by a Fox

metal eye shield, and all further examination and manipulation of the eye

should be discouraged to prevent prolapse or worsening prolapse of

choriouveal structures. Tetanus status should be addressed. Intravenous

antibiotics to cover suspected organisms are appropriate. Adequate

sedation and use of parenteral analgesics is encouraged. Antiemetics

should be given proactively, since vomiting may result in further

prolapse of intraocular contents. CT scanning should be considered if the

presence of a foreign body is suspected.

Clinical Pearls

1. The eyeball may appear

deflated or the anterior chamber excessively deep. Intraocular pressure

will likely be decreased, but measurement should be avoided, since this

may worsen herniation of intraocular contents.

2. Rupture usually occurs where

the sclera is the thinnest, at the point of attachment of extraocular

muscles and at the limbus.

3. Bloody chemosis from scleral

rupture is distinguished from subconjunctival hematoma by bulging of the

conjunctiva. A subconjunctival hematoma is flat in appearance (see Fig.

4.22).

4. A teardrop pupil may easily

be overlooked in the triage process or in the setting of multiple

traumatic injuries.

5. Seidel's test (instillation

of fluorescein and observing for fluorescein streaming away from the

injury) may be used to diagnose subtle perforation (Fig. 4.21).

|

|

|

|

|

Seidel

Test A positive Seidel test

shows aqueous leaking through a corneal perforation while being

observed with the slit lamp. (Courtesy of John D. Mitchell, MD. Used

with permission from Tintinalli JE et al: Emergency Medicine: A

Comprehensive Study Guide, 5th ed. New York:

McGraw-Hill; 2000.)

|

|

|

|

Subconjunctival Hemorrhage

Associated Clinical Features

A subconjunctival hemorrhage or

hematoma occurs with often trivial events such as a cough, sneeze,

Valsalva maneuver, or minor blunt trauma. The patient may present with

some degree of duress secondary to the appearance of the bloody eye. The

blood is usually bright red and appears flat (Fig. 4.22). It is limited

to the bulbar conjunctiva and stops abruptly at the limbus. This

appearance is important to differentiate the lesion from bloody chemosis,

which can occur with scleral rupture. Aside from appearance, this

condition does not cause the patient any pain or diminution in visual

acuity.

|

|

|

|

|

Subconjunctival

Hemorrhage Subconjunctival

hemorrhage in a patient with blunt trauma. The flat appearance of the

hemorrhage indicates its benign nature. (Courtesy of Dallas E. Peak,

MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Scleral rupture, nontraumatic

bloody chemosis (Fig. 4.23), conjunctivitis, iritis, corneal-scleral

laceration, severe hypertension, and coagulopathy may have a similar

appearance or presentation.

|

|

|

|

|

Bloody

Chemosis "Bloody

chemosis" was confused with "subconjunctival

hemorrhage" in this patient with no history of trauma and positive

cranial nerve palsies. Cavernous sinus thrombosis was diagnosed.

(Courtesy of Eric Einfalt, MD.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

No treatment is required. The

patient should be told to expect the blood to be resorbed in 2 to 3 weeks.

Clinical Pearls

1. Subconjunctival hematoma may

be differentiated from bloody chemosis by the flat appearance of the

conjunctival membranes.

2. A subconjunctival hematoma

involving the extreme lateral globe after blunt trauma is very suspicious

for zygomatic arch fracture.

3. Patients with nontraumatic

bloody chemosis should be evaluated for an underlying metabolic

(coagulopathy) or structural (cavernous sinus thrombosis) disorder.

|

|

Traumatic Cataract

Associated Clinical Features

Any trauma to the eye that

disrupts the normal architecture of the lens may result in the

development of a traumatic cataract—a lens opacity (Fig. 4.24). The

mechanism behind cataract formation involves fluid infiltration into the

normally avascular and acellular lens stroma. The lens may be observed to

swell with fluid and become cloudy and opacified. The time course is

usually weeks to months following the original insult. Cataracts that are

large enough may be observed by the naked eye. Those that are within the

central visual field may cause blurring of vision or distortion of light

around objects (e.g., halos).

|

|

|

|

|

Traumatic

Cataract This traumatic

cataract is seen as a large lens opacity overlying the visual axis. A

traumatic iridodialysis is also present. (Courtesy of Dallas E. Peak,

MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Lens dislocation, intraocular

foreign body, hypopyon, corneal abrasion, and hyphema can present with

similar complaints. History and physical examination are helpful in

discriminating most of these conditions from traumatic cataract.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

No specific treatment is rendered

in the ED for cases of delayed traumatic cataract. Routine ophthalmologic

referral is indicated for most cases.

Clinical Pearls

1. Traumatic cataracts are

frequent sequelae of lightning injury. All lightning-strike victims

should be warned of this possibility.

2. Cataracts may also occur as

a result of electric current injury to the vicinity of the cranial vault.

3. Cataracts can be easily

examined using the +10-diopter setting on an ophthalmoscope or in more

detail with a slit lamp.

4. Leukocoria results from a dense

cataract, which causes loss of the red reflex.

5. If a cataract develops

sufficient size and "swells" the lens, the trabecular meshwork

may become blocked, producing glaucoma.

|

|

Chemical Exposure

Associated Clinical Features

Most symptomatic ocular exposures

involve either immediate or delayed onset of eye discomfort accompanied

by one or more of the following: itching, tearing, redness, photophobia,

blurred vision, and/or foreign-body sensation. Conjunctival injection or

chemosis may be noted on examination. Abrupt onset of more severe

symptoms may indicate exposure to caustic alkaline or acidic substances

and should be regarded as a true ocular emergency. Exposure to defensive

sprays or riot-control agents (e.g., Mace or tear gas) causes immediate onset

of severe ocular burning, intense tearing, blepharospasm, and irritation

of the mucous membranes of the nose and oropharynx. Chemical

conjunctivitis in the newborn may stem from the use of silver nitrate

drops at delivery for prophylaxis against Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Many hospitals now favor erythromycin-based ointments.

Differential Diagnosis

Alkali or acid exposure, corneal

foreign body, corneal abrasion, infectious conjunctivitis, and

conjunctival foreign body should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment should begin in the

prehospital arena with immediate and copious irrigation. The patient who

presents acutely with possible caustic exposure should be triaged to

immediate treatment. An attempt should be made to determine the pH of the

conjunctival sac with a broad-range pH paper, though this determination

should not delay the initiation of treatment. Instillation of topical

anesthetic drops will permit a better examination. The conjunctiva should

be closely examined for concretions or foreign body, with eversion of the

upper lid. Any debris should be removed with a moistened cotton-tipped

applicator. If pH determination demonstrates acid or alkali exposure,

irrigation with warmed normal saline (NS) or lactated ringers (LS)

(preferred) solution should begin, using 1-L bags connected through

standard intravenous tubing to a Morgan lens. A minimum of 2-L should be

instilled, followed by a recheck of the pH or reassessment for continued

symptoms. If a normal tear film pH of 7.4 has not been achieved,

irrigation should be continued. Alkali exposures may cause severe injury

due to liquifaction necrosis, which penetrates the deeper tissues (Fig.

4.25). Acids produce a coagulative necrosis, which creates a barrier to

further penetration.

|

|

|

|

|

Alkali

Burn Diffuse opacification of

the cornea occurred from a "lye" burn to the face.

(Courtesy of Stephen Corbett, MD.)

|

|

Irrigation should be strongly

considered after chemical exposure to a non–acid or alkali source.

Many chemicals merely cause irritative symptoms; however, some may also

denude the corneal epithelium and inflame the anterior chamber. All

patients should undergo slit-lamp examination to document corneal

injuries (e.g., abrasions, punctate erosions, opacities) or anterior

chamber inflammation. Antibiotic drops may be indicated, particularly if

corneal injury is noted. Cycloplegics may be of benefit as well to reduce

ciliary spasm and pain in these cases.

Clinical Pearls

1. Immediate onset of severe

symptoms calls for immediate treatment and should prompt consideration of

alkali or acid exposure.

2. Determination of ocular pH

should be made in all cases of chemical exposure.

3. Prolonged (up to 24 h)

irrigation may be needed for alkaline exposures.

4. Concretions from the

exposure agent may form deep in the conjunctival fornices and must be

removed to prevent further injury (Fig. 4.26).

5. Corneal abrasions or

punctate erosions may be a direct result of the chemical agent or from

treatment with irrigation or placement of the Morgan lens.

|

|

|

|

|

Caustic

Burn Adhesions (Symblepharon)

Scarring of both palpebral and bulbar conjunctivae results in severe

adhesions between the lids and the globe. (Courtesy of Arden H.

Wander, MD.)

|

|

|

|