|

Note: Large images and

tables on this page may necessitate printing in landscape mode.

Copyright

©2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved.

Emergency

Medicine Atlas > Part 1. Regional

Anatomy > Chapter 5. Ear, Nose, and Throat

Conditions >

|

Otitis Media

Associated Clinical Features

Children between the ages of 6

months and 2 years are at highest risk of developing acute otitis media

(AOM). Males, North American Eskimos, non-breast-fed infants, and

children with craniofacial anomalies have the highest incidence of AOM.

Additionally, children who contract their first episode prior to their

first birthday, have a sibling with a history of recurrent AOM, are in

day care, or have parents who smoke are at increased risk of recurrent

AOM.

In its most basic form, AOM is

defined as an acute inflammation and effusion of the middle ear. Otoscopy

of the middle ear should focus on color, position, translucency, and

mobility. Compared with the tympanic membrane of a normal ear (Fig. 5.1),

AOM causes the tympanic membrane to appear dull, erythematous or

injected, bulging, and less mobile (Figs. 5.2 and 5.3). Pneumatic

otoscopy and tympanometry enhance accuracy in diagnosing AOM. The light

reflex, normal tympanic membrane landmarks, and malleus become obscured.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Normal

Tympanic Membrane Normal

tympanic membrane anatomy and landmarks. (Courtesy of Richard A.

Chole, MD, PhD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Early

Acute Otitis Media A mildly

erythematous tympanic membrane is seen with a small purulent effusion

in the middle ear. (Courtesy of C. Bruce MacDonald, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

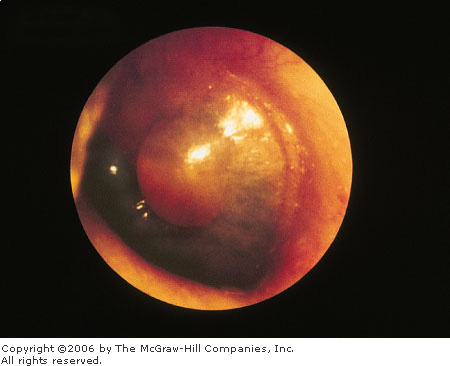

Acute

Otitis Media The middle ear is

filled with purulent material behind an erythematous, bulging

tympanic membrane. (Courtesy of Richard A. Chole, MD, PhD.)

|

|

There are many classifications and hence

presentations of AOM based on symptom duration and clinical presentation.

Regardless of classification, the common pathogenesis of AOM is

eustachian tube dysfunction, allowing retention of secretions (serous

otitis) (Figs. 5.4 and 5.5) and seeding of bacteria.

|

|

|

|

|

Serous

Otitis Media with Effusion (OME)

Copious purulent drainage in a newborn with neonatal gonococcal

conjunctivitis. (Reprinted with permission of the American Academy of

Ophthalmology, Eye Trauma and Emergencies: A Slide-Script Program.

San Francisco, 1985.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Serous

OME A clear, amber-colored

effusion with multiple air-fluid levels is seen in the middle ear

behind a normal tympanic membrane. (Courtesy of C. Bruce MacDonald,

MD.)

|

|

AOM is caused by a wide variety

of viral, bacterial, and fungal pathogens. The most common bacterial

isolates are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae,

Moraxella catarrhalis, and Streptococcus pyogenes.

Approximately 20% of middle ear effusion aspirations are sterile. The

prevalence of  -lactamase–producing

strains of H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis is variable but

increasing. -lactamase–producing

strains of H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis is variable but

increasing.

Patient presentations and

complaints vary with age. Infants with AOM have vague, nonspecific

symptoms such as irritability, lethargy, and decreased oral intake. Young

children can be irritable, often febrile, and frequently pull at their

ears, but they may also be completely asymptomatic. Older children and

adults note ear pain, decreased auditory acuity, and occasionally

otorrhea.

Differential Diagnosis

Myringitis, otitis externa,

perforations of the tympanic membrane, and herpes zoster can mimic otitis

media. Less common causes of ear pain include temporomandibular joint

disorders, odontogenic infections, and sinusitis. Erythema of the

tympanic membrane can appear in an otherwise healthy ear when a child

cries.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Although AOM generally resolves

spontaneously, most patients are treated with antibiotics and analgesics.

Steroids, decongestants, and antihistamines do not alter the course in

AOM but may improve upper respiratory tract symptoms. Rarely, myringotomy

may be needed for pain relief.

Antibiotic selection is widely

variable. Amoxicillin, in the dose range of 80 to 90 mg/kg/day divided

tid, is a suitable first choice for an AOM. Alternatives for initial

therapy include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole,

erythromycin-sulfisoxazole, and second-generation cephalosporins. If the

patient remains symptomatic 48 to 72 h after beginning antibiotics,

amoxicillin with clavulanate, cefixime, or the newer macrolides may

provide broader coverage.

Patients should be instructed to

follow up in 10 to 14 days or return if symptoms persist or worsen after

48 h. Patients who have significant hearing loss, failed two complete

courses of outpatient antibiotics during a single event, have chronic

otitis media (OM) with or without acute exacerbations, or have failed

prophylactic antibiotics warrant referral to an otolaryngologist for

further evaluation, an audiogram, and possible tympanostomy tubes (Fig.

5.6).

|

|

|

|

|

Tympanostomy

Tube Typical appearance of a

tympanostomy tube in the tympanic membrane. These tubes will migrate

to the periphery and eventually drop out. Occasionally, they will be

found in the external ear canal. (Courtesy of C. Bruce MacDonald,

MD.)

|

|

Clinical Pearls

1. In children, recurrent OM is

often due to food allergies.

2. Only 4% of children under 2

years old with OM develop temperatures greater than 104°F. Children with

temperatures higher than 104°F or with signs of systemic toxicity should

be closely evaluated for other causes of the illness before attributing

the fever to OM.

|

|

Bullous Myringitis

Associated Clinical Features

Bullous myringitis is a direct

inflammation and infection of the tympanic membrane (TM) secondary to a

viral or bacterial agent. Vesicles filled with blood or serosanguinous

fluid or bullae on an erythematous tympanic membrane are the hallmark of

bullous myringitis (Fig. 5.7). Frequently a concomitant otitis media with

effusion is noted. Common bacterial agents are Mycoplasma pneumoniae,

Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae.

|

|

|

|

|

Bullous

Myringitis A large

fluid-filled bulla is seen distorting the surface of the tympanic

membrane. (Courtesy of Richard A. Chole, MD, PhD.)

|

|

The onset of bullous myringitis

is preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection and is heralded by

sudden onset of severe ear pain, scant serosanguinous drainage from the

ear canal, and frequently some degree of hearing loss. Otoscopy reveals

bullae on either the inner or outer surface of the TM, often filled with

red bloody fluid. Patients presenting with fever, hearing loss, and

purulent drainage are more likely to have other concomitant infections,

such as otitis media and otitis externa.

Differential Diagnosis

Barotrauma is usually associated

with swimming, diving, or airplane travel. Herpes zoster oticus produces

facial nerve palsy and facial pain. Otitis externa causes edema of the

external auditory canal and drainage, whereas otitis media may distort

the TM but rarely causes bullae.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Differentiation between viral and

bacterial etiologies for tympanic membrane bullae is difficult but,

fortunately, seldom necessary. Although most episodes resolve spontaneously,

many physicians prescribe antibiotics, such as

trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or a macrolide. Warm compresses, topical or

strong systemic analgesics, and oral decongestants may provide

symptomatic relief. Referral is not necessary in most cases unless

rupture of the bullae is required for pain relief.

Clinical Pearl

1. Facial nerve paralysis

associated with clear, fluid-filled TM vesicles is characteristic of

herpes zoster oticus.

|

|

Cholesteatoma and Osteoma

Associated Clinical Features

Contrary to the origin suggested

by their name, cholesteatomas are not neoplasms but rather epidermoid

inclusion cysts: collections of desquamating stratified squamous

epithelium found in the middle ear or mastoid air cells. Congenital

cholesteatomas are most frequently found in children and young adults.

Acquired cholesteatomas originate from perforations of the tympanic

membrane, usually marginally or in the pars flaccida, allowing migration

of stratified squamous epithelium from the external auditory canal into the

middle ear.

Cholesteatomas can be locally

destructive of the middle ear ossicles and tympanic membrane and, through

the production of collagenases, erode into the temporal bone, inner ear

structures, mastoid sinus, or posterior fossa dura. Delays in treatment

can lead to permanent conductive hearing loss or infectious

complications.

Patients present with progressive

hearing loss, foul-smelling ear drainage, and, in advanced stages, pain,

headache, dizziness, facial paralysis, fever, or vertigo. Many cholesteatomas

have an insidious progression without associated pain or symptoms.

Cholesteatomas are seen on otoscopy as either a retraction pocket

containing white debris or a yellow crust on the tympanic membrane with

or without a perforation (Figs. 5.8 and 5.9). A middle ear cholesteatoma

appears as a pearly white or yellow middle ear mass behind the tympanic

membrane, producing a focal bulge, in contrast to the more diffuse

displacement of the tympanic membrane seen in otitis media. Radiographs

and computed tomography (CT) scans may reveal bony destruction.

|

|

|

|

|

Congenital

Cholesteatoma A congenital

cholesteatoma is seen behind an intact tympanic membrane. (Courtesy

of C. Bruce McDonald, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cholesteatoma A cholesteatoma is seen in this ear. Primary

acquired cholesteatomas are thought to arise from gradual

invagination of the pars flaccida, usually secondary to trauma. Note

the yellow epithelial debris from the cholesteatoma in the area of

the pars flaccida. Often there is an effusion and debris, which can

distort the anatomy on otoscopy. (Courtesy of C. Bruce MacDonald,

MD.)

|

|

Osteomas (sometimes called exostoses) are benign

bone overgrowths of the external auditory canal (EAC) found deep in the

meatus. Osteomas are often seen in patients with recurrent cold water

exposures, such as swimmers and divers. Osteomas are seen on otoscopy as

single or multiple round shiny swellings of the bony external auditory

canal (Fig. 5.10). A secondary cerumen impaction or an otitis externa may

obscure the examination.

|

|

|

|

|

Osteomas Multiple osteomas almost occlude the external

auditory canal. The tympanic membrane can be seen in the center, past

the osteomas. These lesions are often seen in patients who are cold

water swimmers. (Courtesy of C. Bruce MacDonald, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Wax particles and EAC foreign

bodies may resemble cholesteatomas on otoscopy. Furuncles are painful to

palpation, whereas otitis externa and otitis media cause EAC drainage and

middle ear effusions, respectively.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Early diagnosis of cholesteatomas

is essential for proper referral. Water avoidance as well as topical and

sometimes systemic antibiotics are important. Small cholesteatomas found

in retraction pockets can be excised and a tympanostomy tube placed to

equilibrate middle ear pressures. More extensive cholesteatomas may

require surgical excision, tympanoplasty, and radical mastoidectomy.

Osteomas require no medical or surgical management unless they become

symptomatic.

Clinical Pearls

1. Persistent pain associated

with headache, facial motor weakness, nystagmus, or vertigo suggests

inner ear or intracranial involvement.

2. Polyps found on the tympanic

membrane can indicate the presence of a cholesteatoma and require further

evaluation to exclude its presence.

|

|

Tympanic Membrane Perforation

Associated Clinical Features

Acute tympanic membrane (TM)

perforations are often the result of direct penetrating trauma, water or

air pressure changes (barotrauma, blast injuries), chronic otitis media,

corrosives, thermal injuries (electricity, lightning, heated objects),

and iatrogenic causes (foreign-body removal, tympanostomy tubes). TM

perforations are occasionally complicated by damage to the ossicular

chain that produces a more complete conductive hearing loss, temporal

bone injuries, and cranial nerve damage.

Patients complain of a sudden

onset of ear pain, vertigo, tinnitus, and altered hearing after a

specific event. Patients with posterior perforations present with a more

profound deafness than those with anterior perforations. Physical

examination of the TM reveals a slit-shaped tear or larger perforation

with an irregular border. An acute perforation can have blood on the

perforation margin and blood or clot in the canal (Fig. 5.11). The

margins are smooth in subacute or chronic perforations.

|

|

|

|

|

Acute

Tympanic Membrane Perforation

An acute tympanic membrane perforation is seen. Note the sharp edges

of the ruptured tympanic membrane. (Courtesy of Richard A. Chole, MD,

PhD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Congenital malformations, chronic

perforations, residual perforations from tympanostomy tubes, and

retraction pockets have more regular borders and no bleeding or TM

erythema.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment of acute tympanic

membrane perforations is tailored to the mechanism. All easily removable

foreign bodies should be extracted. Corrosive exposures require face,

eye, and ear decontamination. Antibiotics and irrigation do not improve

the rate or completeness of healing unless the injury is associated with

OM. Systemic antibiotics should be used for perforations associated with

OM, penetrating injury, and possibly water-sport injuries (see

"Otitis Media," above). Topical steroids impede perforation

closure.

Patients are instructed to avoid

allowing water to get into the ear while the perforation is healing and

to return if symptoms of infection appear. All TM perforations should be

referred to an otolaryngologist for follow-up for possible myringoplasty.

Even though nearly 80% of all TM perforations heal spontaneously, some do

not, and complications can develop.

Clinical Pearls

1. Cortisporin eardrops of any

formulation have been shown to retard spontaneous healing and should be

avoided.

2. Traumatic TM perforation

associated with cranial nerve deficits or persistent vertigo requires

immediate ear/nose/throat (ENT) consultation for possible temporal bone

fractures or injury to the round or oval window.

|

|

Otitis Externa

Associated Clinical Features

Otitis externa (OE), or

"swimmer's ear," is an inflammation and infection (bacterial or

fungal) of the auricle and external auditory canal (EAC). Typical

symptoms include otalgia, pruritus, otorrhea, and hearing loss. Physical

examination reveals EAC hyperemia and edema (Fig. 5.12), otorrhea,

malodorous discharge, occlusion from debris and swelling, pain with

manipulation of the tragus, and periauricular lymphadenopathy.

|

|

|

|

|

Otitis

Externa A discharge is seen

coming from the external auditory canal, which is swollen and almost

completely occluded. An ear wick placed in the EAC facilitates

delivery of topical antibiotic suspension and drainage of debris.

(Courtesy of Frank Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

Several factors predispose the EAC to infection:

increased humidity and heat, water immersion, foreign bodies, trauma,

hearing aids, and cerumen impaction. Bacterial OE is primarily an

infection due to Pseudomonas species or Staphylococcus aureus.

Diabetics are particularly prone to infections by Pseudomonas, Candida

albicans, and, less commonly, Aspergillus niger (Fig. 5.13).

|

|

|

|

|

Aspergillus

Otitis Externa Chronic otitis

externa with copious debris, including black spores from Aspergillus

niger, cottony fungal elements, and wet debris. This patient had

been treated with topical and systemic antibiotics. (Courtesy of C.

Bruce MacDonald, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Cholesteatomas and foreign bodies

can produce a secondary OE. Periauricular cellulitis, herpes zoster

oticus (Fig. 5.14), and malignant otitis externa have auricular and

facial involvement. EAC dermatitis, eczema, and furuncles rarely produce

EAC drainage.

|

|

|

|

|

Herpes

Zoster Oticus Erythema and

drainage coming from the EAC is seen in this patient with herpes

zoster oticus. Otitis externa can have a similar appearance but does

not have vesicles, as seen in this patient. (Courtesy of Robin T.

Cotton, MD.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Saline irrigation and suctioning

is recommended to thoroughly evaluate the EAC. Topical antibiotic suspensions

(containing polymyxin, neomycin, and hydrocortisone or ciprofloxacin)

with ear wicks are effective. Topical solutions are not

pH-balanced and thus are irritating and may cause inflammation in the

middle ear if a perforation is present. Systemic antibiotics are not

indicated unless extension into the periauricular tissues is noted.

Patients should avoid swimming and prevent water from entering the ear

while bathing. Dry heat aids in resolution, and analgesics provide

symptomatic relief. Follow-up should be arranged in 10 days for routine

cases.

Clinical Pearls

1. Resistant cases may have an

allergic or edematous component. These typically present with a dry,

scaly, itchy EAC and are recurrent and chronic in nature.

2. Drying the EAC after water

exposure with a 50:50 mixture of isopropyl alcohol and water or with

acetic acid (white vinegar) minimizes recurrence. If the TM is possibly

perforated, isopropyl alcohol should be avoided.

3. Often the symptoms are out

of proportion to the visible findings, necessitating narcotic analgesia.

|

|

Mastoiditis

Associated Clinical Features

Mastoiditis or acute coalescent

mastoiditis is an infection or inflammation of the mastoid air cells that

usually results from extension of purulent otitis media with progressive

destruction and coalescence of air cells. Medial wall erosion can cause

cavernous sinus thrombosis, facial nerve palsy, meningitis, brain

abscess, and sepsis. With the use of antibiotics for acute otitis media,

the incidence of mastoiditis has fallen sharply.

Patients present with fever,

chills, postauricular ear pain, and frequently discharge from the

external auditory canal. Patients may have tenderness, erythema,

swelling, and fluctuance over the mastoid process; lateral displacement

of the pinna (Fig. 5.15); erythema of the posterior-superior external

auditory canal wall; and purulent otorrhea through a tympanic membrane

perforation.

|

|

|

|

|

Acute

Mastoiditis Postauricular

swelling and redness in a young girl with acute mastoiditis.

(Courtesy of Robin T. Cotton, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Postauricular abscesses,

furuncles, suppurative adenitis, lymphadenitis, and, rarely, carcinomas

of the mastoid can present with signs and symptoms of acute mastoiditis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Initial evaluation includes a

thorough head, neck, and cranial nerve examination while mastoid

radiographs may demonstrate coalescence of the mastoid air cells.

Computed tomography, the diagnostic procedure of choice, may reveal bony

extension and intracranial involvement.

Penicillinase-resistant

penicillins, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, second-generation

cephalosporins, and the newer macrolides are effective in mild cases of

mastoiditis. Severe cases require parenteral semisynthetic penicillins,

cephalosporins, or vancomycin. Mastoiditis requires close follow-up and

prompt consultation.

Clinical Pearls

1. Most patients require

admission for parenteral antibiotics to cover Haemophilus influenzae,

Moraxella catarrhalis, streptococcal species, and Staphylococcus

aureus.

2. Surgical irrigation and

debridement and possibly mastoidectomy are reserved for refractory cases.

3. Delays in treatment can

result in significant morbidity and mortality.

4. Chronic mastoiditis

describes chronic otorrhea of at least 2 months duration. It is often

associated with craniofacial anomalies.

|

|

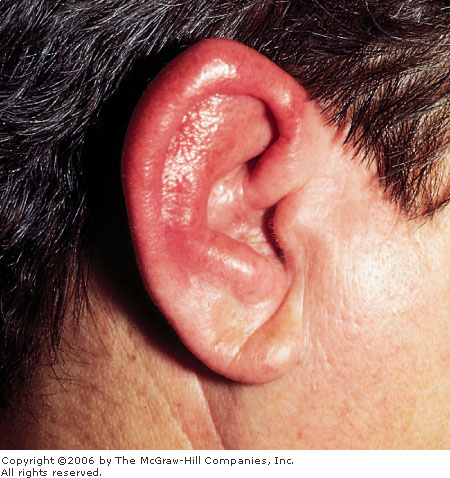

Perichondritis

Associated Clinical Features

Perichondritis is an infection of

the auricular cartilage. It can result from direct trauma; traumatic

hematomas; thermal injuries, typically frostbite; foreign bodies in the

external auditory canal; chronic otitis media; otitis externa; skin

infections; chronic mastoiditis; acupuncture and surgical procedures on

the ear. Destruction and necrosis of the auricular cartilage can lead to

a flaccid, flat ear.

The microbiology of

perichondritis reflects the source of infection. Infections of skin

structures and trauma involve streptococci and staphylococci. Ear and

mastoid sources frequently involve gram-negative organisms. Untreated

perichondritis in elderly diabetic and immunocompromised patients can lead

to malignant external otitis.

Patients present with severe pain

and diffuse swelling of the ear. Physical examination reveals an

erythematous, swollen, warm and tender pinna (Fig. 5.16). Advanced cases

can progress to necrosis of the ear cartilage (chondritis) and spreading

cellulitis.

|

|

|

|

|

Perichondritis The pinna is swollen and erythematous. No

concomitant otitis externa, mastoiditis, or furuncle is noted.

(Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Periauricular cellulitis can

mimic perichondritis but has facial involvement. Auricular hematomas

follow direct trauma. Contact dermatitis can develop from topical ear

medications and jewelry. The first episode of relapsing polychondritis

may be difficult to distinguish from perichondritis. The absence of fever

and history of previous cartilage involvement suggests relapsing

polychondritis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Immediate treatment of

perichondritis is essential to preserve the external ear cartilage. Early

perichondritis is treated by irrigation and debridement of any abscess,

with administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics such as

penicillinase-resistant penicillins, amoxicillin-clavulanate, or

ciprofloxacin. Topical antibiotics are ineffective. A compressive mastoid

and auricular dressing is beneficial. Strict follow-up is essential to

prevent treatment failure and progression of infection. Advanced

perichondritis requires high-dose parenteral antibiotics and early

specialist referral for surgical irrigation and debridement.

Clinical Pearl

1. Early diagnosis and

treatment are necessary to avoid permanent deformity of the pinna.

|

|

Septal Hematoma

Associated Clinical Features

Septal hematomas are an uncommon

complication of direct trauma to the nose. While often associated with

fracture of the nasal septum with or without concomitant nasal bone

fracture, the trauma is typically minor. Septal hematomas may also result

from septal surgery or rhinoplasty. Regardless of the mechanism, bleeding

from submucosal blood vessels leads to an accumulation of blood between

the mucoperichondrium and the septal cartilage. Pressure exerted by the

hematoma on the septal cartilage and its blood supply may lead to

ischemic avascular necrosis of the underlying cartilage, causing

destruction of the cartilage and deformity of the distal nose (saddle

deformity). The hematoma and any necrotic cartilage may then serve as a

nidus for infection, resulting in a septal abscess.

In addition to the cosmetic nasal

deformity, septal hematomas and deformity may lead to chronic sinus

infections, recurrent epistaxis, and sleep disturbances. Rarely, septal

abscesses can result in more serious complications such as cavernous

sinus thrombosis and meningitis. Since the original trauma is often

minor, patients may present days to weeks after the injury. Young

children and infants may present with poor feeding, fever, and rhinorrhea,

while older children and adults may note bleeding, headache, and more

focal pain. Patients with obvious nasal fractures tend to present

earlier.

On nasal examination, the

hematoma appears as a large, red, round swelling originating off the

septum and occluding most of the nasal cavity (Fig. 5.17). The mass is

very painful to palpation and may cause the outer aspects of the nose to

be tender as well. Septal abscesses tend to be more painful and larger

than uncomplicated hematomas. Constitutional symptoms such as fever are

frequently present. The microbiology of septal abscesses reflects the

normal flora of the nasal cavity. Staphylococcus aureus, group A  -hemolytic

streptococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Streptococcus

pneumoniae are the organisms most commonly isolated. -hemolytic

streptococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Streptococcus

pneumoniae are the organisms most commonly isolated.

|

|

|

|

|

Septal

Hematoma A septal hematoma is

seen in both nares in this child. (Courtesy of Robin T. Cotton, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Septal abscesses, foreign bodies,

and nasal polyps may also appear as masses in the nasal cavity.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

An index of suspicion and prompt

recognition are essential in diagnosing septal hematomas. Once

identified, prompt referral to an otolaryngologist is mandatory for

incision of the hematoma and drainage through the mucosal surface.

Purulent drainage should be sent for microbiology and culture.

Many authors recommend packing of

the nasal cavity to prevent further accumulation. Other surgeons use

temporary drains, such as a Penrose, while still others place dissolvable

sutures in the mucoperichondrium to prevent hematoma reaccumulation.

Clinical Pearls

1. Intranasal examination in

all patients with a history of nasal trauma regardless of severity is

crucial.

2. Antibiotics are required in

septal hematomas with a clinical suspicion for a secondary infection or

abscess.

3. The physician must explore

the possibility of child abuse in young children and infants with septal

hematomas and abscesses.

|

|

Herpes Zoster Oticus (Ramsay Hunt Syndrome)

Associated Clinical Features

Herpes zoster oticus (HZO), or

Ramsay Hunt syndrome, is the second most common cause of facial

paralysis, representing 3 to 12% of such patients. The syndrome consists

of facial and neck pain, acoustic symptoms, and facial palsy associated

with the reactivation of varicella zoster in the facial nerve and

geniculate ganglion (Figs. 5.18 and 5.19; see also Fig. 5.14). Patients

first note a pruritus, followed by pain out of proportion to the physical

examination over the face and ear. Patients may note vertigo, hearing

loss (sensorineural) from involvement of the eighth cranial nerve,

tinnitus, rapid onset of facial paralysis, decrease in salivation, loss

of taste sensation over the posterolateral tongue, and vesicles on the

ear, external auditory canal, and face.

|

|

|

|

|

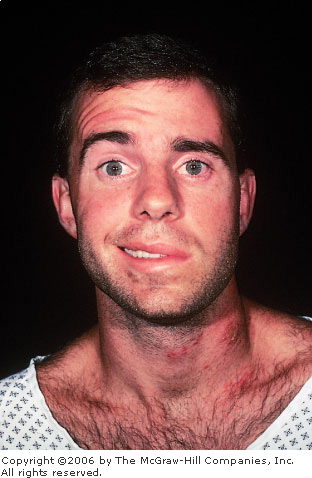

Herpes

Zoster Oticus Facial palsy in

a young adult. Note the vesicular eruptions on the neck. (Courtesy of

Frank Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

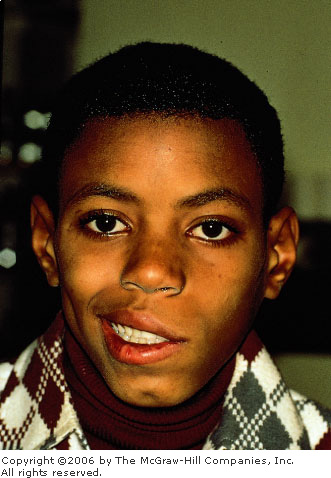

Herpes

Zoster Oticus On closer

examination, the vesicles extend up the neck to the external auditory

canal. (Courtesy of Frank Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Cerebrovascular accidents develop

acutely and do not produce pain in the face or external auditory canal.

Facial paralysis from temporal bone fractures is associated with

antecedent trauma. Ménière's disease can be confused with early HZO but

is painless and does not cause facial paralysis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The diagnosis of HZO is based

largely on history and physical examination. Tzanck preparations may be

difficult because of the vesicles' location. Magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) with contrast may show enhancement of the geniculate ganglion and

facial nerve, but it is not required to make the diagnosis.

Oral acyclovir, 800 mg five times

a day for 7 to 10 days, or famciclovir, 500 mg tid for 7 days in

combination with oral steroids (such as prednisone 60 to 80 mg/day) are

the mainstays for HZO treatment. It is important to protect the involved

eye from corneal abrasions and ulcerations by using lubricating drops.

Clinical Pearl

1. The prognosis for facial

paralysis due to HZO is worse than that for Bell's palsy. Approximately

10 and 66% of patients with full and partial facial paralysis,

respectively, recover fully. The prognosis improves if the symptoms of

HZO are preceded by the vesicular eruption.

|

|

Facial Nerve Palsy

Associated Clinical Features

The seventh cranial or facial

nerve provides innervation of the facial muscles via the five branches of

the motor root; it innervates the submandibular, sublingual, and lacrimal

glands as well as the taste organs on the anterior two-thirds of the

tongue and provides sensation to the pinna of the ear. A seventh-nerve

palsy may occur as an isolated finding or as part of a constellation of

symptoms. Facial palsies are classified as being either central or

peripheral. Central seventh-nerve lesions occur before or proximal to the

seventh-nerve nucleus in the pons. Lesions that occur distal to the

nucleus are classified as peripheral lesions. The hallmark of central lesions

is the sparing of the ipsilateral frontalis muscle (Fig. 5.20), since it

receives innervation in the nucleus from both ipsilateral and

contralateral motor cortices. Peripheral injuries involve the entire side

of the face, including the forehead (Fig. 5.21).

|

|

|

|

|

Central

Seventh-Nerve Palsy Central

facial nerve paralysis with forehead sparing. (Courtesy of Frank

Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Peripheral

Seventh-Nerve Palsy A

peripheral nerve paralysis involving the entire ipsilateral face,

including the forehead, is seen in this patient with Bell's palsy.

(Courtesy of Robin T. Cotton, MD.)

|

|

The most common etiology of

seventh-nerve dysfunction is Bell's palsy, an idiopathic facial nerve

dysfunction. Bell's palsy is most likely a viral or postviral syndrome,

with 60% of patients having a viral prodrome. Bell's palsy shows no age,

sex, or racial predilection. The incidence is higher in pregnant women,

diabetics, and those with a family history of Bell's palsy. It is

bilateral in less than 1% of patients.

Patients with Bell's palsy have

an acute onset of facial weakness and may note numbness or pain on the

ipsilateral face, ear, tongue, and neck as well as a decrease or loss of

ipsilateral tearing and saliva flow. Hearing in Bell's palsy is

preserved.

The prognosis for facial nerve

palsies is variable. Facial weakness—as compared with complete

paralysis—has a better prognosis for full recovery. Facial palsies

due to herpes zoster have a protracted course, and many do not fully

resolve. In comparison, 80% of patients with Bell's palsy due to other

causes completely recover within 3 months. The recurrence rate of Bell's

palsy is 7 to 10%.

Differential Diagnosis

Acoustic neuromas and central

nervous system masses have gradual progression of symptoms and cause

other neurologic findings. Neurologic disorders—such as

Guillain-Barré syndrome, multiple sclerosis, neurosarcoid, and

cerebrovascular accidents—also cause additional neurologic

sequelae. Temporal bone fractures are associated with trauma. The

differential diagnosis also includes infections (otitis media, otitis

externa, HIV) and parotid tumors.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Initial evaluation is directed by

the history. The examination should include a thorough examination of the

ear (including sensorineural or conductive hearing loss), the eye

(including lacrimation), and the cranial nerves. Motor function of the

seventh cranial nerve is evaluated by having the patient raise his or her

eyebrows, smile, pucker, and frown. No single laboratory test is

diagnostic. Screening CT or MRI of the head is of little value in the

absence of additional findings on physical examination.

Most authors empirically

recommend steroids and antiherpetic antivirals for Bell's palsy. A

typical regimen is prednisone, 60 mg a day for 10 days, then tapered, in

combination with acylovir, famcylovir, or valacyclovir. If treated within

the first 3 weeks, steroids may decrease the sequelae of Bell's palsy. In

all facial nerve palsies, eye lubricants and taping or patching of the

eye at night help prevent keratitis and ulceration. Referral to a

specialist should be made for follow-up care.

Clinical Pearls

1. Facial nerve paralysis is a

symptom, not a diagnosis. The etiology of the paralysis must be known

before a diagnosis can be made.

2. If a provisional diagnosis

of Bell's palsy is made and no resolution of symptoms occurs, the

diagnosis must be reconsidered. In patients misdiagnosed with Bell's

palsy, tumors are the most common missed etiology.

3. Lacrimation is tested by the

Schirmer's or litmus test. Asymmetry may indicate a lesion proximal to

the geniculate ganglion.

|

|

Angioedema

Associated Clinical Features

Angioedema is clinically

characterized by acute onset of well-demarcated cutaneous swelling of the

face, lips, and tongue; edema of the mucous membranes of the mouth,

throat, or abdominal viscera; or nonpitting edema of the hands and feet.

Angioedema is classified as either hereditary, allergic, or idiopathic.

Hereditary angioedema is an autosomal dominant trait associated with a

deficiency of serum inhibitor of the activated first component of

complement (C1). Allergic angioedema can result from medications

[nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), contrast agents],

environmental antigens (Hymenoptera), or local trauma. Whatever the

cause, angioedema can be a life-threatening illness. Complications of

angioedema range from dysphagia and dysphonia to respiratory distress,

airway obstruction (Fig. 5.22), and death. Of special interest is angiotensin

converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor–induced angioedema. Angioedema

due to ACE inhibitors has a predilection for involvement of the lips

(Fig. 5.23), face, tongue, and glottis. Standard treatment practices for

allergic urticaria often fail to improve ACE inhibitor–induced

angioedema; in those who do improve, rebound is frequently seen.

|

|

|

|

|

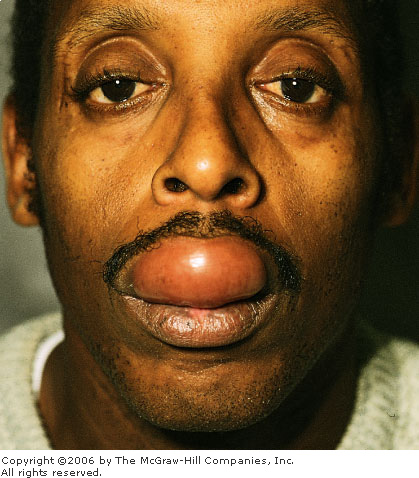

Angioedema Severe angioedema of the face and tongue

requiring emergent cricothyrotomy. (Courtesy of W. Brian Gibler, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ACE

Inhibitor–Induced Angioedema

Angioedema of the upper lip in a man who had been taking an ACE

inhibitor for 2 years. The patient had no previous episodes.

(Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Anaphylaxis and asthma occur in

patients with histories of similar events and involve the lower airways.

Patients with epiglottitis, Ludwig's angina, and peritonsillar or

retropharyngeal abscesses often have a preceding pharyngeal or

odontogenic infection and present with systemic symptoms of infection,

such as fever and chills.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Initial treatment of angioedema

is airway management. Most patients do not require intervention, but

frequent reassessment of the patient's airway is mandatory. Airway interventions

include nasopharyngeal intubation, endotracheal intubation (often

difficult due to lingual and oral obstruction), or nasotracheal

intubation (either blindly or with fiberoptics), or a cricothyrotomy.

Acute angioedema is treated

similarly to an allergic reaction. Depending on the severity of symptoms,

it can be treated with steroids, antihistamines—both H1

and H2 blockers—and subcutaneous epinephrine. Chronic

angioedema responds better to corticosteroids and H2 blockers,

but airway protection remains the primary focus of emergency treatment.

Hereditary angioedema is more refractory to medical interventions;

epinephrine, corticosteroids, and antihistamines provide little relief.

Disposition depends on the

severity and resolution of symptoms. Patients whose symptoms

significantly improve or show no progression after 4 h of observation may

be discharged home on a short course of oral steroids and antihistamines.

Any medication which may have caused the angioedema should be

discontinued. Angioedema with airway involvement requires admission to a

monitored environment, with surgical airway instruments always at the

bedside.

Clinical Pearls

1. Do not underestimate the

degree of airway involvement; act early to preserve airway patency.

2. Angioedema can also cause

gastrointestinal and neurologic involvement.

3. Early response to medical

intervention does not preclude rebound of symptoms to a greater extent

than at presentation.

4. Patients who have been using

ACE inhibitors for months or years can still develop angioedema.

|

|

Pharyngitis

Associated Clinical Features

Pharyngitis is an inflammation

and frequently an infection of the pharynx and its lymphoid tissues,

which make up Waldeyer's ring. Most causes of pharyngitis are infectious

and self-limited, with viral infections accounting for 90% of all cases.

Common bacterial agents include group A beta-hemolytic streptococci

(GABHS, responsible for up to 50% of bacterial cases), other

streptococci, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Neisseria gonorrhea, and Corynebacterium

diphtheriae. In immunocompromised patients and patients on

antibiotics, Candida species can cause thrush. Sore throats that

last longer than 2 weeks should increase suspicion for either a

deep-space neck infection or a neoplastic cause.

Patients with bacterial and

especially GABHS pharyngitis present with an acute onset of sore throat

and fever and frequently nausea, vomiting, headache, and abdominal

cramping. On examination, they may have a mild to moderate fever, an

erythematous posterior pharynx and palatine tonsils, tender cervical

lymphadenopathy, and palatal petechiae (Fig. 5.24). Classically, the

tonsils have a white or yellow exudate with debris in the crypts;

however, many patients may not have exudate on examination. Viral

pharyngitis is typically more benign, with a gradual onset, lower

temperature, and less impressive erythema and swelling of the pharynx.

Except for infectious mononucleosis, which can take weeks to resolve,

most cases of viral pharyngitis are self-limited, with spontaneous resolution

in a matter of days. Lingual and adenoid tonsillitis may also be present

(Fig. 5.25).

|

|

|

|

|

Palatal

Petechiae Palatal petechiae

and erythema of the tonsillar pillars in a patient with streptococcal

pharyngitis. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lingual

Tonsillitis This radiograph

shows lingual and adenoid tonsillitis. (Courtesy of Edward C. Jauch,

MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Deep-space neck infections,

diphtheria, epiglottitis, infectious mononucleosis, and Ludwig's angina

are other infectious causes of sore throats that should be considered.

Allergic rhinitis, angioedema, and pharyngeal neoplasms are noninfectious

causes of similar pharyngeal symptoms. Foreign bodies and local

pharyngeal trauma produce similar symptoms but usually have an antecedent

event.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment is largely symptomatic

except for antibiotics and rehydration. Patients with known or suspected

GABHS require antibiotics primarily to prevent the severe sequelae of the

infection, including rheumatic fever and glomerulonephritis, and

suppurative complications. Current first-line antibiotic therapies remain

a single dose of intramuscular benzathine penicillin or oral penicillin

for 10 days. Patients allergic to penicillin should receive erythromycin

for primary prophylaxis against rheumatic fever. Other suitable

antibiotics include azithromycin or clarithromycin and second-generation

cephalosporins. Analgesics, antipyretics, and throat sprays or gargles can

provide symptomatic relief.

Clinical Pearls

1. The physical examination

should not end at the neck. Auscultation of the chest, palpation of the

abdomen, and examination of the skin are also important.

2. Sore throats or chronic

pharyngitis that lasts more than 2 weeks must be referred for further

evaluation to rule out possible neoplastic or neurologic causes,

especially in patients over 50 years old who have a smoking or chewing

tobacco history.

3. Recurrent tonsillitis in

children merits referral for possible adenoid-tonsillectomy.

4. Amoxicillin should be

avoided if infectious mononucleosis is a possibility, as a diffuse

maculopapular rash will occur in up to 80%.

5. Pharyngitis itself may be a

prodrome for other pathologic conditions, such as measles, scarlet fever,

and influenza.

|

|

Diphtheria

Associated Clinical Features

Diphtheria is a highly contagious

disease caused by the exotoxin-producing bacterium Corynebacterium

diphtheriae. It is transmitted either by direct contact or through

respiratory aerosolization in coughing or sneezing. Many adults are now

susceptible to diphtheria because their vaccine-induced immunity

decreases over time or owing to decreased opportunity for naturally

acquired immunity. Because of this, recent outbreaks have involved

adolescents and adults rather than children.

Prior to the widespread

implementation of childhood vaccines in the 1940s, diphtheria was

associated with significant childhood mortality. While the United States

has only episodic cases of diphtheria, the incidence worldwide is

increasing dramatically because of decreased immunization rates in

developing countries. In the new republics of the former Soviet Union,

over 160,000 new cases and 5000 deaths were reported in the recent

epidemic.

Diphtheria most commonly affects

the mucosa of the upper respiratory tract and less commonly the mucosa of

the nasopharynx, nares, or tracheobronchial tract. Diphtheria typically

produces an ulcerated pharyngeal mucosa with a white to gray inflammatory

pseudomembrane (Fig. 5.26), classically with a "wet mouse"

odor. Patients present with symptoms, in order of frequency, of fever,

sore throat, weakness, pain with swallowing, change in voice, loss of

appetite, neck swelling, difficulty breathing, and nasal discharge.

|

|

|

|

|

Diphtheria

Pharyngitis An exudative

pharyngitis with a gray pseudomembrane is seen in this patient with

diphtheria. (Courtesy of Peter Strebel, MBChB, MPH, and the Journal

of Infectious Diseases.)

|

|

While the organism remains

localized to the mucosa, hematogenous spread of the exotoxin typically

produces myocarditis or peripheral neuropathies. Deaths from diphtheria

occur either from tracheobronchial obstruction by the pseudomembrane

acutely or cardiac complications during the several weeks after the

primary infection.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for

exudative pharyngitis is broad (see "Pharyngitis," above).

Other pathogens that can cause a membranous pharyngitis include Streptococcus

species, Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus, and Candida.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The diagnosis of diphtheria is

initially made clinically. The definitive diagnosis is made by successful

isolation and toxigenicity testing of C. diphtheriae. Cultures

should be taken from beneath the membrane and rapidly placed on a special

culture medium containing tellurite. Histopathologic analysis may also

confirm the disease. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

is investigating a new polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for the

presence of the diphtheria toxin gene.

Treatment is dependent on making

the appropriate diagnosis. Antitoxin, only available from the CDC

(telephone: 404-639-2889), is the mainstay of therapy and must be given

before laboratory confirmation. Similarly, erythromycin or penicillin,

the drugs of choice in treating diphtheria, should be given promptly when

diphtheria is suspected. The recommended treatment course for either

agent is 14 days. Antibiotics have been shown to decrease both exotoxin

production and spread of the bacterium.

Many patients require hospital

admission for airway precautions, pulmonary support, and intravenous

hydration and antibiotics. Strict isolation is essential for patients

with diphtheria, along with proper disposal of all articles soiled by a

patient. All cases should reported to local public health officials to

assist in identifying contacts.

Clinical Pearls

1. Outcome is improved with

early treatment; thus the diagnosis of diphtheria must be made clinically

and treatment begun empirically before bacteriologic confirmation.

2. Patients with a membranous

pharyngitis need to be questioned regarding immunization, exposures, and

travel history.

3. All contacts should have a

booster dose of vaccine (TD or Td, depending on age) while nonimmune

contacts should also be given prophylactic antibiotics after a throat

swab.

4. Travelers to endemic areas

must be current with their diphtheria vaccinations.

|

|

Peritonsillar Abscess

Associated Clinical Features

Peritonsillar abscess, or quinsy,

is the most common deep neck infection. Although most occur in young

adults, immunocompromised and diabetic patients are at increased risk.

Most abscesses develop as a complication of tonsillitis or pharyngitis,

but they can also result from odontogenic spread, recent dental

procedures, and local mucosal trauma. They recur in 10 to 15% of

patients.

The pathogens involved are

similar to those causing tonsillitis, especially streptococcal species,

but many infections are polymicrobial and involve anaerobic bacteria.

Patients present with a fever, severe sore throat that is often out of

proportion to physical findings, localization of symptoms to one side of

the throat, trismus, drooling, dysphagia, dysphonia, fetid breath, and

ipsilateral ear pain.

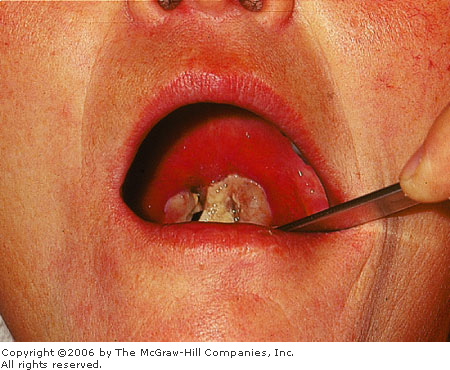

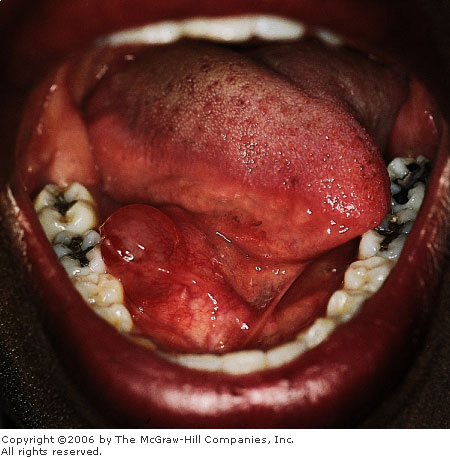

During the early stages, the

tonsil and anterior pillar are erythematous, appear full, and may be

shifted medially. Later, the uvula and soft palate are shifted to the

contralateral side (Fig. 5.27). The tonsillar pillar may feel fluctuant

and tender on palpation.

|

|

|

|

|

Peritonsillar

Abscess Acute peritonsillar

abscess showing medial displacement of the uvula, palatine tonsil,

and anterior pillar. Some trismus is present, as demonstrated by

patient's inability to open the mouth maximally. (Courtesy of Kevin

J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Ludwig's angina, odontogenic neck

infections, peritonsillar cellulitis, and retropharyngeal abscesses can

be confused with peritonsillar abscesses. Angioedema has a rapid onset of

symptoms, whereas oral neoplasms develop slowly.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Most patients with signs of an

abscess can have a needle aspiration performed as the sole surgical

drainage procedure and can expect a satisfactory outcome. Alternative

surgical drainage procedures—including incision and drainage and

abscess tonsillectomy—can be performed by an otolaryngologist or

oral surgeon. Most can be managed as outpatients on oral antibiotics

following drainage. Patients who are immunocompromised, have airway involvement,

appear toxic, or cannot tolerate oral intake require admission for

rehydration, parenteral antibiotics, and specialty consultation.

Studies to date are divided on

the incidence of penicillin-resistant organisms in peritonsillar

abscesses. Although penicillin alone is arguably a good first choice,

penicillin and metronidazole, amoxicillin with clavulanate, clindamycin,

or third-generation cephalosporins are also suitable antibiotic choices.

Clinical Pearl

1. The value of culturing

aspirates is questionable, with a review of several studies showing no

clinical benefit from the cultures unless the patient is

immunocompromised.

|

|

Uvulitis

Associated Clinical Features

The uvula is the fleshy midline

extension of the soft palate that hangs from the roof of the mouth.

Except for idiopathic, the two most common causes of uvular enlargement

are infections and angioedema. Most patients complain of a sore throat, a

gagging sensation, or a foreign-body sensation in the back of the mouth.

The infectious etiologies of

uvulitis are bacterial, including Haemophilus influenzae and

streptococci; fungal, such as Candida albicans; and viral.

Infections of the uvula are typically extensions from adjacent

infections, such as epiglottitis, tonsillitis, peritonsillar abscesses,

and pharyngitis.

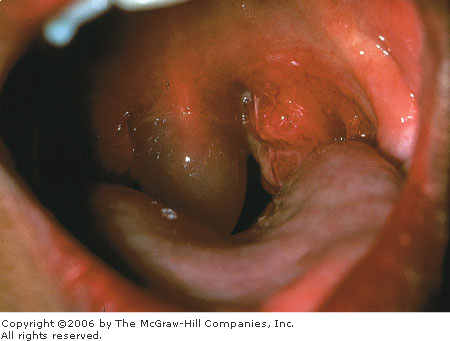

With infectious uvulitis,

patients note fever, odynophagia, trismus, facial pain, hoarseness, neck

pain, and headache. On examination the uvula is red, firm, swollen, and

very tender to palpation.

Angioedema of the uvula, known as

Quincke's disease, can be hereditary, acquired, or idiopathic.

Medications, allergens, thermal stimuli, pressure, and iatrogenic or

accidental trauma can initiate angioedema. In addition to the swollen

uvula, patients may note pruritus, urticaria, and wheezing. With uvular

edema, the angioedema may involve the face, tongue, and oropharynx.

Airway compromise is more common in angioedema of the uvula. The uvula

with angioedema appears pale, boggy, and edematous, resembling a large

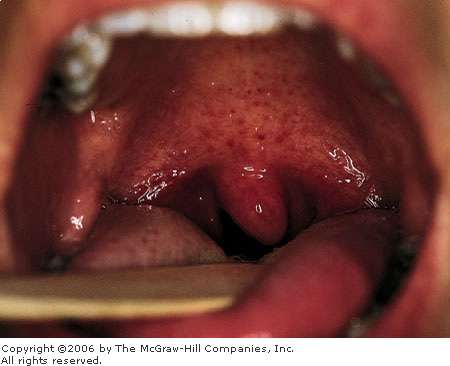

white grape (uvular hydrops) (Fig. 5.28).

|

|

|

|

|

Uvulitis Angioedema of the uvula, known as Quincke's

disease. (Courtesy of Robin T. Cotton, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Benign polyps and neoplasms cause

asymmetry of the palate or uvula. Cellulitis and peritonsillar abscesses

may also cause uvular distortion.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Most cases of uvulitis are benign

and self-limited. Angioedematous uvulitis is treated like any angioedema.

Administration of steroids, antihistamines—both H1 and H2

blockers, and epinephrine, either subcutaneously or nebulized, may

provide symptomatic relief. For infectious uvulitis, antibiotic coverage

is dictated by the primary source of infection. For odontogenic

infections, pharyngitis, or tonsillitis with uvulitis, penicillin,

clindamycin, or amoxicillin with clavulanate are effective. Epiglottitis

associated with uvulitis requires potent H. influenzae coverage,

such as third-generation cephalosporins. Admission is based on severity

of airway compromise and accompanying infections.

Clinical Pearls

1. Although the incidence of

concomitant epiglottitis has decreased dramatically, any airway symptom

dictates an evaluation of the hypopharynx, either by soft tissue lateral

neck radiograph, fiber-optic nasopharyngoscope, or direct laryngoscopy.

2. If the uvula itself is

causing enough airway compromise, uvular decompression by longitudinal

incisions or a partial uvulectomy can be performed.

|

|

Epiglottitis

Associated Clinical Features

Epiglottitis or supraglottitis is

an infection of the supraglottic structures including the epiglottis,

aryepiglottic folds, arytenoids, and periepiglottic soft tissues. Bacterial

epiglottitis, a rare but potentially fatal infection, is caused primarily

by Haemophilus influenzae, but Streptococcus pneumoniae,

Staphylococcus aureus, and  -hemolytic

streptococcus have been isolated. The advent of the H. influenzae B

vaccination for infants has changed what used to be a disease primarily

of children, with a peak age range from 2 to 6 years, to one found

increasingly in adults. Bacterial epiglottitis occurs most commonly in

the winter and spring but may appear at any time. -hemolytic

streptococcus have been isolated. The advent of the H. influenzae B

vaccination for infants has changed what used to be a disease primarily

of children, with a peak age range from 2 to 6 years, to one found

increasingly in adults. Bacterial epiglottitis occurs most commonly in

the winter and spring but may appear at any time.

Patients, especially children,

with acute epiglottitis appear quite ill. They present with sore throat,

fever, drooling, severe dysphagia, dyspnea, muffled or hoarse voice, and

occasionally inspiratory stridor. Patients with severe respiratory

distress assume the "tripod" position: sitting upright with the

neck extended, arms supporting the trunk, and the jaw thrust forward.

This position maximizes airway patency and caliber. Adults typically have

an indolent course with a prodromal viral illness, but many children have

a sudden onset and rapid progression to respiratory distress.

Differential Diagnosis

Croup, bacterial tracheitis,

lingual tonsillitis, and retropharyngeal abscesses are other infectious

causes of respiratory distress. Angioedema and foreign bodies cause a

sudden onset of acute respiratory distress without antecedent illnesses.

Acquired and congenital

subglottic stenosis and intrinsic and extrinsic masses may produce

similar airway symptoms.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Airway management is paramount.

Even prior to diagnosis, children should be calmed, comforted by a

parent, and allowed to assume whatever position they feel is most comfortable.

Anesthesiology and ENT should be consulted immediately. Indications for

intubation are clinical, but severe stridor and respiratory distress are

clear reasons to intervene. Nasotracheal intubation in children is

preferred but not when performed blindly. Needle cricothyrotomy can

provide temporary oxygenation until a surgical airway is provided.

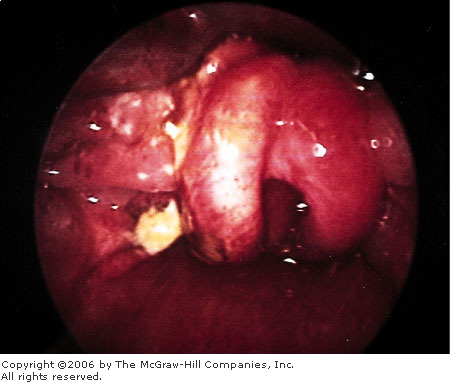

Radiographs of the neck may

reveal the classic "thumb" sign, a thickened epiglottis on the

lateral soft-tissue neck radiograph (Fig. 5.29). Visualization of the

epiglottis is possible in the stable adult patient via direct and

indirect laryngoscopy and fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy (Fig. 5.30). The

airway orifice may be difficult to see because of the extreme distortion

of tissues. In children, the top of the swollen epiglottis may be

visualized on careful oral examination, whereas pharyngoscopy is

typically reserved for an experienced anesthesiologist or

otolaryngologist in a controlled setting.

|

|

|

|

|

Adult

Epiglottitis Soft-tissue

lateral neck radiograph of an adult with epiglottitis demonstrating

the classic "thumb" sign of a swollen epiglottis. (Courtesy

of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adult

Epiglottitis Fiberoptic

laryngoscopy showing a red, edematous epiglottis and glottic area

with marked airway compromise in an adult with epiglottitis.

(Courtesy of Timothy L. Smith, MD.)

|

|

The mainstay of epiglottitis

treatment is antibiotics. Second- and third-generation parenteral

cephalosporins and ampicillin with sulbactam have proven efficacy in

treating epiglottitis.

Steroids or epinephrine, either

nebulized or subcutaneous, may provide some improvement in edema.

Recently, helium and oxygen gas mixtures—which, owing to their

lower density compared with air, improve the work of breathing and flow

rates—have shown promise in delaying or even preventing intubation

in some patients.

In addition to airway compromise,

complications of epiglottitis include epiglottic abscesses, meningitis,

pulmonary edema, pneumonia, and empyema (associated with H. influenzae).

Clinical Pearls

1. Transport of patients with

suspected epiglottitis must be done by an experienced transport team. The

airway must be secured before transport of all but the most stable

patients.

2. During intubation, pushing

on the patient's chest may cause a bubble to form at the airway orifice,

guiding placement of the tube.

3. Failure to intervene prior

to loss of the airway carries a sixfold increase in mortality.

|

|

Mucocele (Ranula)

Associated Clinical Features

Ranulas are mucoceles (mucous

retention cysts) that develop in the floor of the mouth, arising from

obstructed sublingual or submandibular ducts or smaller minor salivary

glands. At first the cysts are small and barely noticeable, but over time

they can expand outward or deeper into the neck (plunging ranula). Large

cysts can displace the tongue forward and upward, making the patient

uncomfortable. Unlike those with sialolithiasis, patients with ranulas

may not always notice an increase in swelling associated with eating.

Physical examination reveals a soft, minimally tender, translucent cyst

with dilated veins running over its surface (Fig. 5.31). Unlike

carcinomas, no ulceration is noted with ranulas, and they are generally

softer.

|

|

|

|

|

Ranula Sublingual ranula, or mucocele, lateral to

Wharton's duct. The patient was asymptomatic except for being aware

of the lesion. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Torus mandibularis is a hard bony

growth off the lingual surface of the mandible. Obstruction of major

salivary glands is often painful and intermittent. Carcinomas of the

mouth are slower-growing and firm. Abscesses and local cellulitis also

produce sublingual swelling.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Recognition by the physician is

essential for proper referral. Definitive treatment is excision or

marsupialization, although needle aspiration of the cyst can provide

temporary relief. Unless there is a secondary infection, no antibiotic

coverage is required.

Clinical Pearls

1. Most ranulas are painless

and are incidental findings on routine examinations.

2. Ranulas often recur,

requiring total excision of the offending salivary gland.

|

|

Sialoadenitis

Associated Clinical Features

Sialoadenitis is a general

term describing inflammation of any salivary gland. The three major

salivary gland pairs are the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual.

There are also numerous smaller salivary glands that empty into the oral

cavity and all are capable of becoming inflamed. Salivary gland disorders

have a broad spectrum of causes, including acute and chronic infections;

metabolic, systemic, and endocrine disorders; infiltrative processes;

obstructions; allergic inflammation; and neoplastic diseases. Key

features in the history are the duration and course of the symptoms,

complaints of pain, and unilateral or bilateral location.

Both viral and bacterial

infections of the salivary gland can lead to enlarged, swollen, painful

masses. Suppurative sialoadenitis is most commonly caused by Staphylococcus

aureus and is found in patients who are elderly, diabetic, or have

poor oral hygiene. It may also follow episodes of dehydration, such as

those due to surgery or debilitation. Viral sialoadenitis, such as mumps

parotitis, is the most common cause. It occurs with a concomitant viral

illness and is usually bilateral, whereas bacterial infections are

primarily unilateral.

Obstructive sialoadenitis occurs

from a stone or calculus in the salivary gland or duct, most commonly in

the submandibular gland. The flow of saliva is obstructed, causing

swelling, pain, and firmness. Patients with sialolithiasis note general

xerostomia and recurrent worsening of swelling and pain during mealtime.

A thorough head and neck

examination is essential, especially a bimanual examination of the major

salivary glands. In suppurative sialoadenitis, purulent drainage may be

expressed from the submandibular duct (Wharton's) or parotid duct

(Stensen's), and the glands are very tender and painful to examination

(Figs. 5.32, 5.33). Sialolithiasis can manifest as enlargement of the

ducts with minimal saliva expressed on stripping and, rarely, a palpable

or visible stone (Fig. 5.34) or duct thickening. Facial radiographs are

of limited utility. Ultrasound or CT may be useful to detect abscesses.

|

|

|

|

|

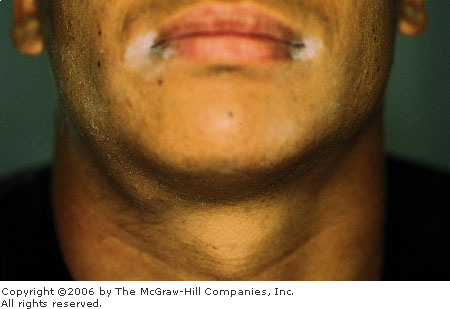

Suppurative

Parotid Sialoadenitis Painful

swelling over the right parotid initially had clear saliva from

Stensen's duct. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Suppurative

Parotid Sialoadenitis After applying

firm pressure on the cheek, purulent discharge is seen coming from

Stensen's duct. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Suppurative

Submandibular Sialoadenitis

Unilateral submandibular swelling. (Courtesy of Jeffery D. Bondesson,

MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Tumors of the face and

oropharynx, particularly primary salivary neoplasms and secondary lymphatic

metastases, develop slowly and produce firm, minimally tender nodules and

clear saliva. Cutaneous and odontogenic infections, angioedema variants,

and lymphadenitis may mimic sialoadenitis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment of suppurative

sialoadenitis (Figs. 5.34, 5.35) requires antibiotics with coverage of Staphylococcus

and oral flora, rehydration, proper oral hygiene, sialogogues, local

heat, and occasionally surgical irrigation and drainage of abscesses.

Obstructive sialoadenitis is rarely an emergency. Most salivary stones

(Fig. 5.36) pass spontaneously without complication, and patients can be

discharged home on lozenges to stimulate salivary secretions and expel

the stone. Prompt follow-up of sialoadenitis is essential to prevent

possible morbidity and mortality associated with infections or neoplasms.

|

|

|

|

|

Suppurative

Submandibular Sialoadenitis

After applying firm pressure, purulent discharge is seen coming from

Wharton's duct. (Courtesy of Jeffery D. Bondesson, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sialolithiasis A stone is seen at the orifice of Wharton's

duct. (Courtesy of David P. Kretzschmar, DDS, MS.)

|

|

Clinical Pearls

1. Examine secretions of both

mouth and eyes and elicit any history of dry eyes, keratoconjunctivitis,

cutaneous lesions, or rheumatoid arthritis to establish the diagnosis of

a systemic disorder.

2. Medications such as

antihistamines, psychotropic drugs, and those possessing atropine-like

side effects can cause xerostomia.

3. Lack of improvement on

antibiotics suggests an abscess or multiple loculated abscesses that

require drainage.

|

|

Sinusitis

Associated Clinical Features

Sinusitis is an inflammation of

the paranasal sinuses. Sinusitis can be classified as acute, subacute, or

chronic; purulent or sterile; and allergic or nonallergic. All share an

impairment of mucus clearance. Most cases of bacterial sinusitis are

associated with antecedent viral upper respiratory tract infection.

Maxillary sinusitis is the most

common form of sinusitis and is associated with paranasal facial pain,

maxillary dental pain, purulent rhinorrhea (Fig. 5.37), retroocular pain,

and conjunctivitis. Ethmoid sinusitis is more common in children and

produces a low-grade fever and periorbital pain. Frontal sinusitis can cause

a severe headache above the eyes, which is exacerbated by leaning

forward; a low-grade fever; upper lid edema; and rhinorrhea. Sphenoid

sinusitis is fortunately rare. Patients classically complain of a vertex

headache and retroocular pain. Owing to its intracranial location,

sphenoid sinusitis can involve several cranial nerves, the pituitary

gland, and the cavernous sinus. Involvement of all sinus cavities is

referred to as pansinusitis. Important complications of sinusitis include

periorbital and orbital cellulitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and

intracranial abscess (Figs. 5.38 and 5.39).

|

|

|

|

|

Sinusitis Purulent drainage from the maxillary sinus

ostium in a patient with maxillary sinusitis. Drainage may not always

be apparent, since the ostium may be occluded from swelling and

inflammation. (Courtesy of Robin T. Cotton, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

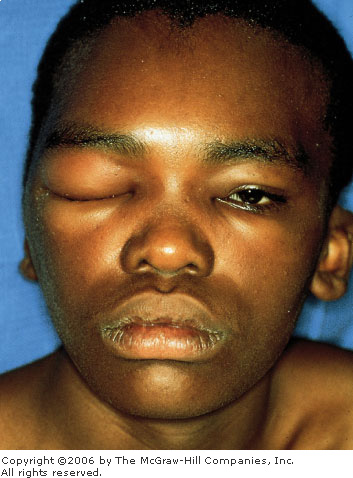

Sinusitis Adolescent with pansinusitis complicated by

periorbital cellulitis. The patient was also found to have

osteomyelitis of the frontal cortex (Pott's puffy tumor). (Courtesy

of Robin T. Cotton, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sinusitis Waters view of the patient in Fig. 5.37

showing an air-fluid level in the right frontal and bilateral

maxillary sinuses. (Courtesy of Robin T. Cotton, MD.)

|

|

Patients with Pott's puffy tumor

(a rare osteomyelitis of the cranium from direct extension of a frontal

sinusitis) present with a boggy, tender swelling above the eye.

A careful history is important in

patients presumed to have sinusitis. Recent steroid use, prodromal viral

illness, dental work, and facial trauma are important temporal events. A

history of septal deviation or defects, cystic fibrosis, smoking, and

cocaine use also increases the risk of sinusitis.

Imaging modalities include

transillumination of the maxillary sinuses, plain radiographs, CT, and

MRI. CT is the most sensitive and specific technique and allows for

better delineation of the sphenoid and ethmoid sinuses.

Common bacterial isolates are Haemophilus

influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae (together representing 60 to 70%

of all bacterial causes), Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus

aureus, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Immunocompromised patients

are susceptible to fungal infections, including Aspergillus and Mucor

species.

Differential Diagnosis

Other infections—including

facial cellulitis, early herpes zoster, odontogenic infections, and

otitis media—may produce similar signs and symptoms. Neoplasms and

trigeminal neuralgia should also be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

For acute bacterial sinusitis,

amoxicillin, macrolides, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are

appropriate agents. Refractory cases or immunocompromised patients

require broader-spectrum antibiotics such as amoxicillin with

clavulanate, clarithromycin, second- or third-generation cephalo-sporins,

or the newer fluoroquinolones. Treatment for up to 3 weeks may be

necessary.

Decongestants reduce local edema,

increase air movement within the sinuses, and decrease local secretions.

A short course of topical oxymetazoline or phenylephrine as well as oral

pseudoephedrine for 10 days helps minimize secretions and assists in

maintaining ostia patency. Humidified air, steam, or saline nasal sprays

also facilitate drainage. Patients should be strongly encouraged to stop

smoking.

Parenteral steroids are not used

in acute or recurrent sinusitis. Inhaled steroids, such as triamcinolone,

have a role in allergic and chronic sinusitis.

Referral or follow-up by an

otolaryngologist or primary care provider should be made for all patients

within 3 weeks for routine cases. Patients with comorbid illnesses or

more complicated sinusitis should be admitted for parenteral antibiotic

therapy and supportive care.

Clinical Pearls

1. Chronic sinusitis may be due

to mucoid retention cysts, deviated septum, or polyps, which are often

visible on plain radiographs. Refer these patients for possible surgery.

2. Physicians must consider

fungal etiologies in patients with comorbid illnesses.

|

|