|

Note: Large images and

tables on this page may necessitate printing in landscape mode.

Copyright

©2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved.

Emergency

Medicine Atlas > Part 1. Regional

Anatomy > Chapter 6. Mouth > Oral

Trauma >

|

Tooth Subluxation

Associated Clinical Features

Tooth subluxation refers to the

loosening of a tooth in its alveolar socket. Traumatic oral injury is a

common mechanism by which dental subluxation occurs; however, infection

and chronic periodontal disease may also produce loosening of teeth.

Gingival lacerations and alveolar fractures are commonly associated with

dental subluxations. Subluxated, or loosened, teeth are diagnosed by

applying gentle pressure to the teeth with a tongue blade or fingertip.

Mild displacement may also be noted (Fig. 6.1). Blood along the crevice

of the gingiva, where the tooth meets the gingiva, is also a sign of

subluxation. Various degrees of tooth mobility may be noted on

examination.

|

|

|

|

|

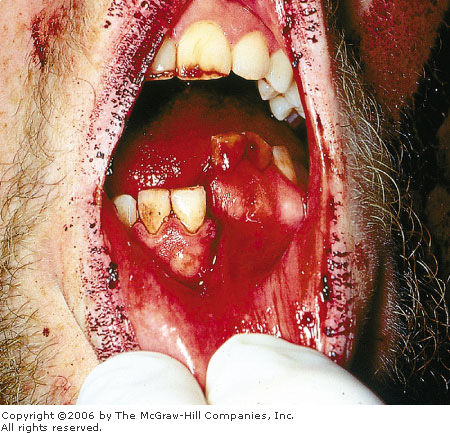

Tooth

Subluxation Note the presence

of blood along the crevice of the gingival margin of both central

incisors—an indication of subluxation following trauma. Mild

displacement of the subluxated teeth is noted. (Courtesy of James F.

Steiner, DDS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Dental impaction and alveolar

ridge fracture should be considered and ruled out clinically and with

radiographs.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

1. Primary teeth:If the

subluxated tooth is forced into close proximity to the underlying

permanent tooth, extraction by a dentist or oral surgeon is indicated.

Otherwise, the patient should be instructed to follow a soft diet for 1

to 2 weeks, allowing the tooth to reimplant.

2. Permanent teeth:If

the tooth is unstable, it should be temporarily immobilized. This may be

accomplished with gauze packing, a figure-eight suture around the tooth

and an adjacent tooth, aluminum foil, or a special periodontal dressing

(Coe-Pak). The patient should be referred for dental follow-up.

Clinical Pearls

1. Any evidence of tooth

mobility following trauma is a subluxation by definition.

2. Always consider the

possibility of an associated underlying alveolar fracture.

3. Clinically subluxated teeth

may actually represent an occult root fracture.

|

|

Tooth Impaction (Intrusive Luxation)

Associated Clinical Features

Impacted or intruded teeth result

when a tooth is forced deeper into the alveolar socket or surrounding

tissues as a result of trauma (Fig. 6.2). The force causing the impaction

may be directly on the incisal or occlusal surface of the tooth. The tooth

appears shorter than its contralateral partner. The primary dentition is

more prone to impaction than permanent teeth. An impacted tooth may be

partially visible or completely hidden by the gingiva and buried in the

alveolar process. Completely impacted teeth may erroneously be considered

avulsed until a radiograph demonstrates the intruded position. The apex

of a completely impacted permanent central incisor may be driven through

the alveolar bone into the floor of the nostril, causing a nosebleed. The

apex of the incisor may be noted on examination of the nostril floor.

Primary dentition apices tend to be driven into the thin vestibular bone.

Other associated injuries include possible alveolar fractures, dental

crown or root fractures, as well as oral mucosal and gingival

lacerations. Dental pulp necrosis occurs in 15 to 50% of cases.

|

|

|

|

|

Tooth

Intrusion This impaction

injury with multiple anterior maxillary tooth involvement shows

various degrees of tooth impaction. Also note the complete absence of

a central incisor. This may indicate a complete intrusion into the

alveolar socket or an avulsion of the tooth. Radiographic studies are

required when a tooth's location is in question. (Courtesy of James

F. Steiner, DDS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Tooth avulsions and fractures

should be considered in the differential diagnosis because of a similar

mechanism of injury. Completely impacted teeth may simulate an avulsed

tooth in appearance. Lateral luxation may result in teeth that appear

shortened and angulated or may simulate a partial impaction. Traumatic

injury to gingiva around a normal erupting tooth may be mistaken for an

impaction. Impacted teeth tend to emit a high metallic sound on

percussion testing with a metallic instrument, similar to ankylosed

teeth. Normal teeth do not produce a metallic sound, whereas subluxated

teeth produce a dull sound on percussion. Radiographs also aid in

differentiating these dental injuries.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Primary teeth that are impacted

usually reerupt and reposition spontaneously within 1 to 3 months.

Surgical intervention is indicated if spontaneous reduction does not

occur within this time frame. Any intruded primary tooth whose apex is

displaced toward or impacts on the follicle of its permanent successor

should be extracted. These patients should have dental follow-up and be

monitored clinically and radiographically for 1 year. Permanent teeth do

not reerupt. Surgical reduction is indicated to prevent complications

such as external root resorption and loss of supporting bone. Orthodontic

repositioning and splinting is generally carried out over 3 to 4 weeks.

Follow-up for a minimum of 1 year is recommended.

Clinical Pearls

1. An undiagnosed impacted

tooth is predisposed to infection and can have a poor cosmetic result.

2. The maxillary incisors are

the most commonly affected teeth.

3. Only the immature primary

teeth will reerupt; the permanent teeth will not.

|

|

Tooth Avulsion

Associated Clinical Features

Avulsion is the total

displacement of a tooth from its socket (Fig. 6.3). There is usually a

history of trauma; however, infectious etiologies can also cause an

avulsion. Complete disruption of the periodontal ligament fibers from the

affected tooth occurs as a result. Various degrees of bleeding from the

socket and surrounding gingiva may be noted. Depending on the mechanism

of injury, there may be an associated underlying alveolar fracture.

Prompt inquiry into the location of any unaccountable tooth is indicated.

Radiographic evaluation to rule out aspiration or soft tissue entrapment

is indicated when the tooth's location is in question.

|

|

|

|

|

Tooth

Avulsion Avulsion injury with

angulation and displacement of teeth from the alveolar socket.

(Courtesy of James F. Steiner, DDS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Complete tooth impactions may

appear to be an avulsion. Dental fractures with retained tooth fragments

in the alveolar socket may also simulate an avulsion. Radiographs should

be taken to rule out an intrusion or dentoalveolar fracture.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Permanent teeth should be

replaced in their sockets as soon as possible. The tooth should first be

rinsed with saline but not scrubbed, and the root should not be handled.

Successful reimplantation depends on the survival of periodontal ligament

fibers, which are attached to the root of the avulsed tooth. The tooth

should be placed in the socket and emergent dental consultation obtained.

Antibiotics against mouth flora (penicillin, clindamycin) should be

administered, as well as tetanus prophylaxis. If not replaced, the

avulsed tooth should be stored in the mouth of the patient or parent or

in a container of milk. Normal saline can be used, but water should not

be used. Hank's solution is the ideal storage medium for the avulsed

tooth until reimplantation. Primary teeth are not reimplanted, but

follow-up should be obtained, as a procedure may be needed to maintain

tooth spacing until the permanent tooth erupts.

Clinical Pearls

1. Reimplantation of primary

avulsed teeth in patients younger than 6 years may interfere with

eruptions of permanent teeth because of ankylosing and fusion to the

bone.

2. Successful reimplantation of

an avulsed tooth is best achieved within the first 30 min after an avulsion.

3. Storage and transport media

in decreasing order for preserving tooth viability include Hank's

balanced salt solution or a tissue culture medium (Save-A-Tooth), cool

low-fat or skim milk, saline, and saliva.

|

|

Tooth Fractures

Associated Clinical Features

Anatomically, each tooth has

crown and root portions. Externally, the crown is covered with white

enamel and the root portion with cementum. The cementoenamel junction

(cervical line) is where the crown and root meet. The yellow-to-tan

dentin is the second innermost layer and composes the bulk of the tooth.

The red-to-pink pulp tissue is located in the center of the tooth and

furnishes the neurovascular supply to the tooth. The Ellis classification

system, while considered by some as inadequate, is still commonly used to

describe tooth fractures above the cervical line in anterior teeth (Fig.

6.4):

|

|

|

|

|

Tooth

Fractures Enamel, dentin, and

pulp are the anatomic landmarks used in the Ellis classification of

tooth fractures.

|

|

Ellis class I: Involves the

enamel only (Fig. 6.5).

Ellis class II: Involves the

enamel plus exposure of the dentin (Fig. 6.6). The patient may complain

of temperature sensitivity.

Ellis class III: Fracture

extends into the pulp. A pink or bloody discoloration on the fracture

surface is diagnostic of this type of fracture (Fig. 6.7). The patient

may have severe pain but may also have no pain due to loss of nerve

function.

Tooth fractures may also occur

below the cementoenamel junction. These dental root fractures are

commonly missed on initial evaluation. Bleeding may be observed at the

gingival crevice with associated tooth tenderness on percussion.

|

|

|

|

|

Ellis

Class I Tooth Fracture Note

the fracture of the left upper central incisor. The sole involvement

of the enamel is consistent with an Ellis type I injury. (Courtesy of

James F. Steiner, DDS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ellis

Class II Tooth Fractures

Bilateral maxillary central incisor injuries with exposed enamel and

dentin consistent with an Ellis class II fracture. (Courtesy of James

F. Steiner, DDS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ellis

Class III Tooth Fracture A

fracture demonstrating blood at the exposed dental pulp. This sign is

pathognomonic for an Ellis class III fracture. (Courtesy of Kevin J.

Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Subluxation, alveolar fracture,

avulsion, or a traumatic impaction are in the differential. Dental

fractures may also be occult and occur below the gum line or at the level

of root. Radiographic evaluation will aid in differentiating these

conditions.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Ellis class I: Pain control

should be initiated. Rough tooth edges may be smoothed with an emery

board. Immediate dental referral within 24 h is indicated when soft

tissue injury is caused by sharp pieces of the tooth.

Ellis class II: Patients

under 12 years of age have less dentin than older patients and are at

risk for infection of the pulp. They should have a calcium hydroxide

dressing placed, coverage with gauze or aluminum foil, and see a dentist

within 24 h. Older patients should be advised to see a dentist within 24

to 48 h.

Ellis class III: This is

considered a dental emergency, and immediate dental consultation is

indicated. Delay in treatment may result in severe pain and abscess

formation.

Root Fractures: Early

reduction, immobilization, and splinting are indicated once diagnosed. A

commercial stabilizing compound (Coe-Pak) is available for this purpose.

Dental referral is advised within 24 to 48 h. Most teeth sustaining root

fractures maintain pulpal vitality and tend to heal.

Clinical Pearls

1. Check for tooth mobility on

initial examination to aid in differentiating mobility involving the

entire tooth from involvement of only the incisal segment.

2. Consider nonaccidental

trauma when dental injuries occur in young children.

|

|

Alveolar Ridge Fracture

Associated Clinical Features

The alveolus is the tooth-bearing

segment of the mandible and maxilla. Fracture of the alveolar process

tends to occur more often in the thinner maxilla than in the mandible.

However, the most common type of mandibular fracture is an alveolar

fracture. The anterior alveolar processes are at greatest risk for

fracture due to more direct exposure to trauma (Fig. 6.8). Exposed pieces

of bone may be noted in alveolar fractures. Various degrees of tooth

mobility and gingival bleeding may be noted. Both subluxation and

avulsion of teeth may be associated with underlying alveolar fractures of

the mandible or maxilla.

|

|

|

|

|

Alveolar

Ridge Fracture Note the

exposed alveolar bone segment and associated multiple tooth

involvement. Attempts should be made to maximally preserve all viable

tissue. (Courtesy of Alan B. Storrow, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Fractures of the mandible and

maxilla may both present with pain, deformity, malocclusion, and

bleeding, which may resemble an alveolar fracture. Gingival lacerations

with significant tissue damage may be associated with an underlying

fracture and should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Preservation of as much viable

tissue as possible is important. Do not remove any segment of alveolus

firmly attached to the mucoperiosteum. Significant cosmetic deformity may

result from alveolar bone loss. The involved alveolar segment should have

a saline-soaked gauze applied with gentle direct pressure. Any avulsed

teeth should also be preserved. The patient's tetanus status should be

addressed. Antibiotic therapy with penicillin, clindamycin, or a

cephalosporin should also be considered, particularly if bony fragments

are exposed. Oral surgery consultation should be obtained for possible

wire stabilization, arch bar fixation, and follow-up.

Clinical Pearls

1. Always consider the

possibility of an associated cervical spine injury when evaluating

patients with facial trauma.

2. If an avulsed tooth is

associated with an alveolar fracture, the clinician should inquire about

its location. If unaccounted for, consider the possibility of aspiration

or soft tissue entrapment.

|

|

Temporal Mandibular Joint (TMJ) Dislocation

Associated Clinical Features

Dislocation generally results

from direct trauma to the chin while the mouth is open or, more commonly,

in predisposed individuals after a vigorous yawn. Opening the mouth

excessively wide while eating or laughing may also result in dislocation.

Acute dislocation occurs when the mandibular condyles displace forward

and become locked anterior to the articular eminence. Muscle spasm

contributes to prevention of spontaneous relocation. Weakness of the

temporomandibular ligament, an overstretched joint capsule, and a shallow

articular eminence are predisposing factors. Patients usually present

with an inability to close an open mouth (Fig. 6.9). Other associated

symptoms include pain, discomfort, and facial swelling near the

temporomandibular joint (TMJ). Difficulty speaking and swallowing is

common. Anterior dislocations are most common; however, posterior

dislocation may occur with significant force in association with a

basilar skull fracture. Unilateral dislocation results in deviation of

the mandible to the unaffected side (Fig. 6.10).

|

|

|

|

|

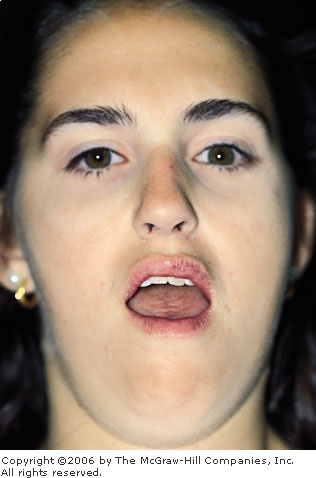

TMJ

Dislocation (Bilateral) This

patient awoke from sleep with the inability to close her mouth. Note

the dry lips and tongue secondary to prolonged exposure. Symmetric

dislocations are more common than unilateral injury. (Courtesy of

Warren K. Russell, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TMJ

Dislocation (Unilateral) Note

the asymmetric jaw deviation toward the unaffected side. Always

consider the possibility of an associated underlying fracture or

cervical spine injury. (Courtesy of Frank Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

TMJ hemarthrosis, dystonic

reactions, and hysterical dislocation can mimic the true process of TMJ

dislocation. Unilateral or bilateral mandibular fractures should also be

strongly considered, particularly if there is a history of facial trauma.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Acute reduction of pain, muscle

spasm, and anxiety is achieved using reassurance, analgesics, and muscle

relaxants. Panorex or TMJ x-ray films (pre- and postreduction) are

obtained to exclude a fracture (Fig. 6.11). The patient is typically

treated in the sitting position. While facing the patient, the physician

grasps the angles of the mandible with both hands. The thumbs are wrapped

in gauze for protection and rest on the occlusive surfaces of the molars

while downward and backward pressure is applied until the condyle slides

back into the articular eminence. Instruct the patient to avoid

excessively wide mouth opening while eating and yawning for 3 to 4 weeks.

Apply warm compresses to the TMJ areas. A soft diet for 1 week is advised,

as is the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as needed. Dental

follow-up should be arranged.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TMJ

Dislocation A. Radiographic

demonstration of an anterior TMJ dislocation. The location of the

condyle is indicated by the open arrow. The position of the

mandibular notch is indicated by the closed arrow. B. Postreduction

radiograph showing normal positioning of the condyle in the

mandibular notch. (Courtesy of Edwin D. Turner, MD.)

|

|

Clinical Pearls

1. Approximately 70% of the general

population can subluxate the mandible partially and then spontaneously

reduce it.

2. TMJ dysfunction secondary to

a neuroleptic or antipsychotic medication–related dystonic reaction

is treated with diphenhydramine or benztropine.

3. When trauma is the cause of

TMJ dislocation, maintain a high index of suspicion for cervical spine

injury.

|

|

Tongue Laceration

Associated Clinical Features

Tongue lacerations are usually

the result of oral trauma and tongue biting (Fig. 6.12). Injuries to the

tongue or mouth floor can cause serious hemorrhage and potential airway

compromise. Careful examination of the oral cavity for associated

injuries is necessary. Specifically, the injury or absence of teeth

should be ascertained. Dorsal tongue lacerations may be associated with a

concurrent ventral laceration sustained from the mandibular teeth.

Closely inspect the wound for possibly entrapped dental elements.

|

|

|

|

|

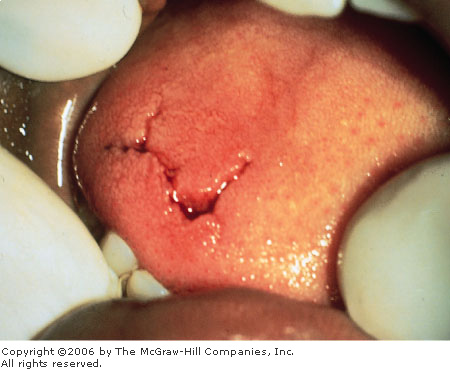

Tongue

Laceration A stellate tongue

laceration that does not require suturing is shown. The ventral

aspect of the tongue should be examined for additional lacerations

sustained from the mandibular teeth. (Courtesy of James F. Steiner,

DDS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Superficial tongue abrasions,

oral mucosal, and gingival lacerations may all bleed profusely and cause

difficulty localizing the exact source. Any of the aforementioned

lacerations may also accompany a tongue laceration. A detailed

examination of the entire oral cavity is indicated.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Most lacerations to the tongue do

not mandate surgical repair. A generous blood supply results in

spontaneous repair of most tongue defects. An exception to this rule is

lacerations involving the tip, where rapid healing may produce a

"forked tongue." Lacerations greater than 1 cm in length that

gape widely, actively bleed, or those involving a lateral margin are best

stabilized by a few well-placed sutures; 4-0 black silk or preferably

absorbable suture (such as chromic gut) should be used. Place sutures

using large bites to include both mucosa and muscle. Laceration repair,

if opted for in children, is best carried out in a controlled environment

under appropriate anesthesia. Anesthesia of the anterior two-thirds of

the tongue is obtained using a regional inferior alveolar nerve block

(blocks the lingual nerve on the ipsilateral side). Local anesthesia may

also be used. Tongue lacerations involving the floor of the mouth or

having persistent bleeding may result in tongue swelling and airway

compromise. Consultation for admission with airway surveillance may be

indicated.

Clinical Pearls

1. If repair is elected, use an

absorbable or braided suture material. Multiple well-secured knots should

be placed, as tongue motion tends to untie suture material.

2. Extensive complex tongue

lacerations are at risk for infection and should be prophylactically

treated with antibiotics for oropharyngeal flora.

|

|

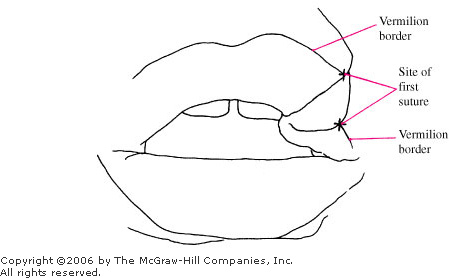

Vermilion Border Lip Laceration

Associated Clinical Features

Anatomically, the vermilion

border of the lips represents a transition area from mucosal tissue to

skin. Lip lacerations involving the vermilion border (Fig. 6.13) present

a unique clinical situation, since inadequate repair may cause an

unacceptable cosmetic result. Marked tissue edema is frequently noted

with most lip trauma, which may distort the anatomy. Vermilion border

lacerations may be partial or full thickness through the lip to the

mucosal surface. An associated underlying gingival or dental injury is a

common finding.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vermilion

Border Lip Laceration A lip

laceration with disruption of the vermilion border. Wound repair

begins at the vermilion-skin junction for a good cosmetic result.

(Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Vermilion border lip hematomas,

abrasions, and soft tissue swelling may mimic a true laceration involving

the vermilion border. Careful examination of the facial and mucosal

surfaces of the lip help differentiate these entities.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Accurate vermilion margin

reapproximation is the goal of lip repairs. An unapproximated vermilion

margin of 2 mm or greater results in a cosmetic deformity and

occasionally a puckering defect. A regional block of the mental or

infraorbital nerve is recommended for anesthesia to avoid additional

tissue edema and anatomic distortion produced by local infiltration.

After closure of the deeper tissue, the first skin suture is always

placed at the vermilion border to reestablish the anatomic margin. Using

5-0 or 6-0 nylon, suturing should continue along the vermilion surface

until the moist mucous membrane is noted. Deep or through-and-through

lacerations involving the vermilion border should be closed in layers.

The deep muscular and dermal layer may be closed with 3-0 or 4-0 chromic

or Vicryl sutures, and the skin with 6-0 nylon sutures. Mucosal layers

are loosely reapproximated with 4-0 absorbable suture or silk. The

patient should be given wound care instructions. Follow-up for wound

evaluation and possible suture removal in 5 to 7 days should be arranged.

Clinical Pearls

1. A vermilion border with as

little as 2 mm of malalignment may produce a cosmetically noticed defect.

2. Always place the first skin

suture in the vermilion border in any lip laceration involving this area.

|

|

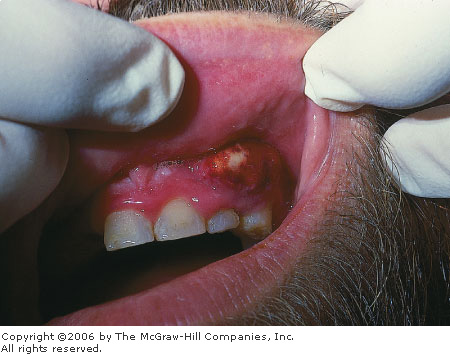

Gingival Abscess (Periodontal Abscess)

Associated Clinical Features

Gingival abscesses tend to

involve the marginal gingiva and result from entrapment of food and

plaque debris in a gingival pocket with subsequent staphylococcal,

streptococcal, anaerobic, or mixed bacterial overgrowth, leading to

abscess formation. Localized swelling, erythema, tenderness, and possible

fluctuance in the space between the tooth and the gingiva (the so-called

pocket) is the usual location. There may be spontaneous purulent drainage

from the gingival margin, or an area of pointing may be seen. In cases of

acute gingival abscess formation, pus may be expressed from the gingival

margin by gentle digital pressure. When the gingival abscess involves the

deeper supporting periodontal structures, it is referred to as a

periodontal abscess (Fig. 6.14). This may present as a fluctuant

vestibular abscess or with a draining sinus that opens onto the gingival

surface.

|

|

|

|

|

Periodontal

Abscess Localized gingival

swelling, erythema, and fluctuance are seen in this periodontal

abscess with spontaneous purulent drainage. (Courtesy of Kevin J.

Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Periapical abscesses are deep and

not obvious on inspection. They usually present as tenderness to

percussion or pain with chewing over the involved tooth. A parulis may

also simulate a gingival abscess; however, a parulis represents the

cutaneous manifestation of a deeper periapical abscess. Unlike a parulis

or periapical abscesses, gingival abscesses are not usually associated

with dental caries or fillings. Pericoronal abscesses tend to involve the

gingiva overlying a partially erupted third molar.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The initial management is a small

incision with drainage and warm saline irrigation. Removal of entrapped

food and debris is performed. Oral antibiotic therapy with penicillin,

clindamycin, tetracyclines, or macrolides is recommended. Analgesics

should be provided along with dental follow-up. The patient's tetanus

status should be addressed.

Clinical Pearls

1. Patients with gingival

abscesses are usually afebrile.

2. Consider more extensive

abscess formation and oral disease processes in the febrile

toxic-appearing patient.

3. Patients with chronic, deep

periodontal abscesses complain of dull, gnawing pain as well as a desire

to bite down on and grind the tooth.

|

|

Periapical Abscess (Dentoalveolar Abscess)

Associated Clinical Features

Acute pain, swelling, and mild

tooth elevation is characteristic of a periapical abscess. Exquisite

sensitivity to percussion or chewing on the involved tooth is a common

sign. The involved tooth may have had a root canal treatment, a filling,

or a dental carie. Periapical abscesses may enlarge over time and

"point," internally on the lingual or buccal mucosal surfaces

or extraorally with swelling and redness of the overlying skin (Fig.

6.15). Occasionally these lesions may tract up to the alveolar periosteum

and gingival surface to form a parulis ("gumboil") (Fig. 6.16).

Radiographically, these abscesses appear as well-circumscribed areas of

radiolucency at the dental apex or along the lateral aspect of the root

(Fig. 6.17). Early acute periapical abscesses may not demonstrate any

radiographic changes. Both deep periodontal and periapical abscesses may

have sinuses draining purulent material onto the gingival surface. If the

infection is allowed to progress, it can erode through the nearest

cortical bone, manifesting itself in a variety of locations (Fig. 6.18).

|

|

|

|

|

Periapical

Abscess This periapical

abscess points externally, to the overlying skin. (Courtesy of Robin

Cotton, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Gumboil"

(Parulis) This lesion is an

extension of a periapical abscess. It is differentiated from a

periodontal abscess by tenderness to percussion. (Courtesy of Alan B.

Storrow, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Periapical

Abscess A. Note the

well-defined radiolucent area at the apex and lateral root of the

tooth in this radiograph. (Courtesy of James L. Kretzschmar, DDS, MS.)

B. This panorex film shows several areas consistent with periapical

abscesses. (Courtesy of David P. Kretzschmar, DDS, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Odontogenic

Abscesses As infection

progresses from the pulp at the tooth apex, it erodes through the

bone and can express itself in a variety of places. This illustration

notes several possible locations or spaces. (Adapted with permission

from Cummings C, Schuller D (eds): Otolaryngology Head and Neck

Surgery. Chicago: Mosby-Year Book; 1986.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Gingival or deep periodontal

abscess, buccal space abscess, and unilateral sublingual, parapharyngeal,

and submandibular space abscesses should all be considered in the

differential diagnosis. All the aforementioned may present with oral

pain, tenderness, facial swelling, and possible fever. Panorex films,

dental radiographs, or a computed tomography (CT) scan may aid in making

the diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs (NSAIDs) or oral narcotics for pain should be administered as well

as oropharyngeal antibiotic therapy. A regional nerve block may be

performed with a local anesthetic agent for more immediate temporary

relief. Administer tetanus toxoid if indicated. Dental consultation or

follow-up in 1 to 2 days is recommended for endodontic evaluation or

possible extraction of the involved tooth. Incision and drainage along

with saline irrigation and prompt referral constitutes the initial

treatment of a parulis.

Clinical Pearls

1. More than one tooth may be

involved simultaneously.

2. Exquisite tenderness and

pain on tooth percussion is a key feature on physical examination and

identifies the involved tooth.

3. Periapical abscesses are

almost always associated with carious or nonviable teeth.

|

|

Pericoronal Abscess

Associated Clinical Features

A partially erupted or impacted

third molar (wisdom tooth) is the most common site of pericoronitis and

pericoronal abscesses. The accumulation of food and debris between the

overlying gingival flap and crown of the tooth sets up the foci for

pericoronitis and subsequent abscess formation. The gingival flap becomes

irritated and inflamed. The area is also repeatedly traumatized by the

opposing molar tooth and may interfere with complete jaw closure as

swelling and tenderness increase. The inflamed gingival process may

eventually become infected and form a fluctuant abscess (Fig. 6.19). Foul

taste, inability to close the jaw, and fever may occur. Swelling of the

cheek and angle of the jaw as well as localized lymphadenopathy are also

characteristic. More advanced disease may spread posteriorly to the base

of the tongue and oropharyngeal area. Potential spread into the deep

cervical spaces is also an important concern with extensive processes.

|

|

|

|

|

Pericoronal

Abscess Note the inflammed

fluctuant gingival tissue approximating the incompletely erupted

third molar. (Courtesy of James F. Steiner, DDS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Ludwig's angina, peritonsillar

abscess, gingival abscess, buccal space abscess, and a severe periapical

abscess may all present similarly to a pericoronal abscess. Ludwig's

angina and peritonsillar abscesses are, in fact, potential sequelae of

acute pericoronitis and pericoronal abscesses.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Superficial incision and drainage

with warm saline irrigation may be performed initially in the ED.

Adequate analgesia and antibiotic coverage should be provided.

Consultation or referral to an oral maxillofacial surgeon for follow-up

is indicated for possible extraction of the involved teeth.

Clinical Pearls

1. Pericoronitis and abscess

formation rarely occur in the pediatric population and tend to be late

adolescent and adult processes.

2. The mandibular third molar

is the most commonly involved tooth.

3. Airway compromise is a

potential complication with posterior extension of a pericoronal abscess.

|

|

Buccal Space Abscess

Associated Clinical Features

The buccal space lies

anatomically between the buccinator muscle and the overlying superficial

fascia and skin. The maxillary second and third molars are the usual

source of infection contributing to buccal space abscesses. Infection

from the involved teeth erodes through the maxillary alveolar bone

superiorly into the buccal space (Fig. 6.20). Rarely, the third

mandibular molar may be the source. In this instance, the infection

erodes through the mandibular alveolar bone inferiorly into the buccal

space. These patients present with unilateral facial swelling, redness,

and tenderness to the cheek (Fig. 6.21). Trismus is generally not

present.

|

|

|

|

|

Buccal

Space Anatomy The buccal space

lies between the buccinator muscle and the overlying skin and

superficial fascia. This potential space may become involved by

maxillary or mandibular molars. (Adapted with permission from

Cummings C, Schuller D (eds): Otolaryngology Head and Neck

Surgery, 2d ed. Chicago: Mosby-Year Book; 1993.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Buccal

Space Abscess Note the ovoid

cheek swelling with sparing of the nasolabial fold. This finding,

along with accompanying redness and tenderness, helps to identify

buccal space abscess formation. (Courtesy of Michael J. Nowicki, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Canine space abscess,

parapharyngeal abscess, facial cellulitis, Ludwig's angina, and

masticator space abscess formation are all conditions that may resemble

buccal space abscesses. Parotid gland enlargement due to mumps and

suppurative bacterial parotitis should also be considered. The former

lacks erythema and warmth of the overlying skin, while the latter is

accompanied by trismus and the ability to express pus from Stensen's

duct. Inspection of all the maxillary and third mandibular molar teeth is

essential to help make the diagnosis. CT scan can aid in localizing the

space involved.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Parenteral antibiotic therapy

with penicillin, clindamycin, or a third-generation cephalosporin is

recommended. Antibiotic coverage for anaerobic organisms may also be

added to the treatment regimen. NSAIDs or mild oral narcotic analgesics

should be provided as indicated. Dental or oral surgical consultation is

necessary for intramural abscess drainage and endodontic therapy versus

extraction of the involved molar teeth.

Clinical Pearls

1. Ovoid cheek swelling with

sparing of the nasolabial fold helps to identify buccal space abscesses

and differentiates it from canine space abscesses.

2. Odontogenic infections of

the second or third maxillary molars is the most common source for buccal

space abscesses.

|

|

Canine Space Abscess

Associated Clinical Features

The canine space lies between the

anterior surface of the maxilla and levator labii superioris muscle of

the face. The origin of these abscesses can be from upper anterior teeth

and bicuspids, although it is almost exclusively from the maxillary

canine tooth. Erosion of maxillary tooth infection through the alveolar

bone into the canine space leads to abscess formation, although cutaneous

infections from the upper lip and nose are a rare source. Unilateral

facial redness, pain, and swelling lateral to the nose with obliteration

of the nasolabial fold is characteristic (Fig. 6.22). Severe upper lip

and lower eyelid swelling may cause eye closure and drooling at the

corner of the mouth.

|

|

|

|

|

Canine

Space Abscess Unilateral

facial swelling lateral to the nose with associated redness and the

typical loss of the nasolabial fold is shown. The maxillary canine

tooth is usually the source of this process. (Courtesy of Frank

Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Buccal space infection, facial

cellulitis, and maxillary sinusitis may present with various clinical

features similar to canine space abscesses. Examination of the anterior

maxillary teeth may provide very helpful clues to the origin and

diagnosis of canine space abscesses. CT scan and sinus x-rays may aid in

defining these lesions.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Parenteral antibiotic therapy to

include anaerobic coverage is indicated for treatment. Dental or oral

surgical consultation for intramural incision and drainage represents the

most definitive treatment for canine space abscesses. Extraction or

endodontic treatment of the involved anterior maxillary teeth is usually

necessary.

Clinical Pearls

1. The maxillary canine

(cuspid) teeth are the most common source for canine space abscesses.

2. Although these patients may

drool when significant upper lip swelling is present, they typically do

not have trismus, dysphagia, or odynophagia.

3. Loss of the nasolabial fold

is characteristic of canine space abscesses.

|

|

Ludwig's Angina

Associated Clinical Features

Ludwig's angina is defined as

bilateral cellulitis of the submandibular and sublingual spaces (see Fig.

6.18) with associated tongue elevation (Figs. 6.23 and 6.24). A

characteristic painful, brawny induration is present rather than

fluctuance in the involved tissue. The posterior mandibular molars

represent the usual odontogenic origin for the infection. Streptococcus,

Staphylococcus, and Bacteroides species are the most common

offending pathogens. Affected individuals are usually 20 to 60 years old,

with a male predominance. These patients are usually febrile and may

demonstrate impressive trismus, dysphonia, and odynophagia. Dysphagia and

drooling are secondary to tongue displacement and oropharyngeal swelling.

Potential airway compromise or spread of the infection to the deep

cervical layers and the mediastinum is possible. The presence of dyspnea

or cyanosis is a later, more ominous sign, which indicates impending

airway closure.

|

|

|

|

|

Ludwig's

Angina Note the diffuse

submandibular swelling and fullness. Direct palpation of this area

would reveal a characteristic brawny induration. Potential airway

compromise is a key concern in all patients with Ludwig's angina.

(Courtesy of Jeffrey Finkelstein, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ludwig's

Angina Note the presence of

subcutaneous gas in the abscessed submandibular area on this

radiograph of a patient with Ludwig's angina. (Courtesy of Edward C.

Jauch, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Peritonsillar abscesses,

epiglottitis, and parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal abscesses all have

clinical features similar in presentation to Ludwig's angina.

Oropharyngeal examination is often uncomfortable and difficult in all the

aforementioned conditions. Caution should be used if epiglottitis is

suspected.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Acute laryngospasm with airway

compromise is a potentially life-threatening complication and concern

with Ludwig's angina; therefore, plans for definitive airway management

should be prepared. Up to one-third require intubation or surgical airway

placement. Parenteral antibiotic therapy can be initiated with penicillin

or a third-generation cephalosporin. Coverage for anaerobic organisms

should also be provided with clindamycin or metronidazole. The role of

steroids is controversial and ill defined for potential airway edema in

this setting. Parenteral analgesic should be given as needed. The

definitive treatment is intraoperative surgical drainage of the abscess.

Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used

to identify abscess location. Admission to the intensive care unit is

indicated for airway surveillance and management. Oral and maxillofacial

surgical or otolaryngologic consultation is prudent.

Clinical Pearls

1. The second mandibular molar

is the most common site of origin for Ludwig's angina.

2. Admission of these patients

to the intensive care unit is almost always indicated because of the

potential for airway compromise.

3. Intraoperative surgical

incision and drainage is the definitive treatment.

4. Brawny submandibular

induration and tongue elevation are common and characteristic clinical

findings.

5. Acute laryngospasm with

sudden total airway obstruction may be precipitated by attempts at oral

or blind nasal intubation.

|

|

Parapharyngeal Space Abscess

Associated Clinical Features

The parapharyngeal space is also

known as the lateral pharyngeal or pharyngomaxillary space. Anatomically

it is a pyramid-shaped space with its apex at the hyoid bone and base at

the base of the skull. Laterally it is bound by the internal pterygoid

muscle and parotid gland with the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle

medially. The posterior aspect of this space is in close proximity with

the carotid sheath and cranial nerves IX through XII. Presenting symptoms

include fever, dysphagia, odynophagia, drooling, and ipsilateral otalgia.

Unilateral neck and jaw angle facial swelling, in association with

rigidity and limited neck motion, is common (Fig. 6.25). Potentially

disastrous complications that have been associated with infections of

this space include cranial neuropathies, jugular vein septic

thrombophlebitis, and erosion into the carotid artery. The origin of

parapharyngeal abscesses may be from infected tonsils, sinuses and teeth,

or lymphatic spread.

|

|

|

|

|

Parapharyngeal

Space Abscess Unilateral

facial, jaw angle, and neck swelling is seen in this patient. Nuchal

rigidity may also be present. (Courtesy of Sara-Jo Gahm, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Buccal space abscess, Ludwig's

angina, peritonsillar and retropharyngeal abscesses, and parotitis

represent clinical conditions to consider. A CT scan provides more

specific information and aids in making the diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Preparations for definitive

airway management via endotracheal intubation or surgery is vital. Early

recognition and anticipation of other potentially disastrous

complications should be considered and managed appropriately.

Broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage for mixed aerobic and anaerobic

infections should be initiated. Radiologic modalities used to assess

parapharyngeal and other deep space neck infections include

contrast-enhanced CT, ultrasound, plain radiography, and MRI.

Otolaryngologic or oral surgical consultation is warranted for definitive

intraoperative incision and drainage of the abscess.

Clinical Pearls

1. Suspected oropharyngeal

abscesses in association with neuropathy in cranial nerves IX through XII

is pathognomonic of parapharyngeal abscesses.

2. Bacterial pharyngitis

represents the most common source of parapharyngeal abscesses.

|

|

Trench Mouth (Acute Necrotizing Ulcerative

Gingivitis)

Associated Clinical Features

Painful, severely edematous interdental

papillae is characteristic of acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis

(ANUG). Other associated features include the presence of ulcers with an

overlying grayish pseudomembrane and "punched out" appearance

(Fig. 6.26). The inflamed gingival tissue is very friable, necrotic, and

represents an acute destructive disease process of the periodontium.

Fever, malaise, and regional lymphadenopathy are commonly associated

signs. Patients may also complain of foul breath and a strong metallic

taste. Poor oral hygiene, emotional stress, smoking, and

immunocompromised states (e.g., HIV, steroid use, diabetes) all may

contribute to predisposition for ANUG. Anaerobic Fusobacterium and

spirochetes are the predominate bacterial organisms involved. The

anterior incisor and posterior molar gingival regions are the most

commonly affected oral tissue.

|

|

|

|

|

Acute

Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis

Note the inflamed, friable, and necrotic gingival tissue. An

overlying grayish pseudomembrane or punched out ulcerations of the

interdental papillae are pathognomonic. (Courtesy of David P.

Kretzschmar, DDS, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis,

aphthous stomatitis, desquamative gingivitis, gonococcal and

streptococcal gingivostomatitis, and chronic periodontal disease all

represent oral diseases that may mimic ANUG. Differentiating these oral

conditions from one another is based primarily on history and a thorough

oropharyngeal examination.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Initial management includes warm

saline irrigation. Systemic analgesics and topical anesthetics such as

viscous lidocaine may facilitate oral hygiene measures. Antibiotic

treatment is initiated immediately with oropharyngeal coverage. Dilute

1.5 to 2% hydrogen peroxide or chlorhexidine oral rinses are also

helpful. Follow-up with a dentist or periodontist in 1 to 2 days is

recommended. Patients with more advanced disease may require admission

and oral surgical consultation.

Clinical Pearls

1. Dramatic relief of symptoms

within 24 h of initiating antibiotics and supportive treatment is

characteristic.

2. Periodontal abscesses and

underlying alveolar bone destruction are common complications of ANUG and

require dental follow-up.

3. There is no evidence that

ANUG is a communicable disease.

4. Gingivitis is a nontender

inflammatory disorder.

5. Consider HIV testing in

patients with ANUG refractory to antibiotic therapy.

|

|

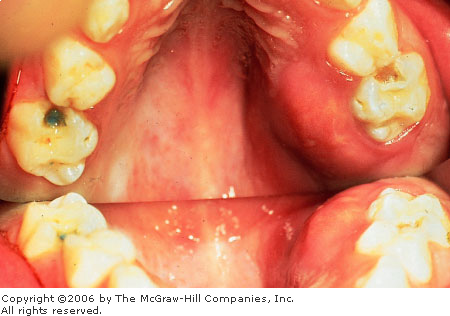

Acid Tooth Erosion (Bulimia)

Associated Clinical Features

Bulimia nervosa is an eating

disorder—thought to be psychological in origin—with

significant associated physical complications. It is characterized by

binge eating with self-induced vomiting, laxative use, dieting, and

exercise to prevent weight gain. Patients with bulimia are at significant

risk for damage to the dental enamel and dentin as a result of repeated

episodes of vomiting. Chronic exposure to regurgitated acidic gastric

contents represents the main mechanism of injury, which is aggravated by

tongue movement. The lingual dental surfaces are most commonly affected

(Fig. 6.27). In severe cases, all surfaces of the teeth may be affected.

Buccal dental surface erosions may be noted as a result of excessive

consumption of fruit (i.e., lemons) and juices by some bulimic patients.

Trauma to the oral and esophageal mucosa may also result from induced

vomiting. The quantity, buffering capacity, and pH of both the resting

and stimulated saliva are found to be reduced. Salivary gland

enlargement, most commonly the parotid, may occur in bulimic persons as

well. Unexplained elevation of serum amylase, hypokalemia, esophagitis,

menstrual irregularities, and fluctuating weight are other complications

noted with bulimia.

|

|

|

|

|

Acid

Tooth Erosion (Bulimia)

Erosive dentin exposure of the maxillary teeth secondary to chronic

vomiting. The involvement of the lingual dental surfaces is

characteristic of bulimia. (Courtesy of David P. Kretzschmar, DDS,

MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Included in the differential

diagnosis of acid tooth erosion are conditions that involve vomiting,

such as pregnancy, stricture or spasm of the esophagus, and disturbances

of gastrointestinal tract peristalsis. Xerostomia is a condition of

excessive mouth dryness (associated with Sjögren's syndrome) and can also

accelerate the process of enamel loss. Conditions resulting in short-term

episodes of vomiting do not have severe destructive effects on the

dentition. Dental abrasions and erosions, singly or in combination, may

result in a considerable loss of tooth structure. Tooth erosions may be

brought about by the use of chewing tobacco (Fig. 6.28), eating betel

nuts, dentifrice, bruxism, abnormal swallowing, and clenching.

|

|

|

|

|

Acid

Tooth Erosion (Snuff User)

Note the typical dentin exposure on the buccal dental surfaces

resulting from prolonged snuff use and its accompanying acid erosion.

(Courtesy of David P. Kretzschmar, DDS, MS.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Dental treatment should begin

with vigorous oral hygiene to prevent further destruction of tooth

structures. Regular professional fluoride treatments to cover exposed

dentin should be instituted, as well as pain treatment. With the

exception of temporary cosmetic procedures, definitive dental treatment

should be deferred until the patient is adequately stabilized

psychologically. The initial ED management of patients with bulimia

should address any medical complication of the disorder like hypokalemia,

metabolic acidosis, and its associated cardiac, renal, and central

nervous system effects. Hospitalization to stabilize medical

complications and provide nutritional support may be indicated. A

multidisciplinary team approach is necessary and should involve

psychiatry, internal medicine, and dental consultation as needed.

Clinical Pearls

1. The lingual surfaces of the

teeth are the most commonly involved tooth surfaces.

2. Attrition or bruxism tends

to cause enamel loss from occlusal and incisal dental surfaces.

3. The labial and buccal

surfaces of the teeth tend to show enamel loss from repeat or prolonged

chemical contact (e.g., lemon sucking or tobacco products).

|

|

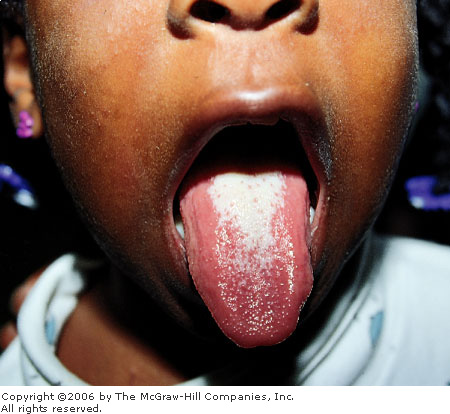

Thrush (Oral Candidiasis)

Associated Clinical Features

White, flaky, curd-like plaques

covering the tongue and buccal mucosa with an erythematous base is

typical of thrush (Fig. 6.29). These lesions tend to be painless;

however, painful inflammatory erosions or ulcers may be noted,

particularly in adults. Decreased oral intake secondary to pain is

common. Colonization of surface epithelium by Candida may be

opportunistic as a result of an altered oral milieu. Predisposing factors

include antibiotic use, corticosteroids, radiation to the head and neck,

extremes of ages, patients with immunologic deficiencies, and chronic

irritation (e.g., denture use and xerostomia).

|

|

|

|

|

Oral

Candidiasis (Thrush) Whitish

plaques are seen here on the buccal mucosa. These plaques are easily

removed with a tongue blade, differentiating them from lichen planus

or leukoplakia. (Courtesy of James F. Steiner, DDS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Hairy leukoplakia, lingual lichen

planus, flecks of milk or food debris, and liquid antacid adhering to the

tongue may be confused with candidiasis. Hairy leukoplakia cannot be

brushed off with a tongue depressor. This helps differentiate this

process from thrush or residue from ingested materials. Microscopic

examination of the removed specimen for the presence of hyphae in

potassium hydroxide mount will aid in the identification of Candida.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Nystatin oral tablets, nystatin

suspension, or clotrimazole oral troches are usually adequate therapy.

Topical analgesic cocktails may also provide comfort for patients (e.g.,

Maalox, diphenhydramine, viscous lidocaine oral rinse).

Clinical Pearls

1. Thrush is most common in

premature infants and immunosuppressed patients.

2. In young adults, thrush may

be the first sign of AIDS; a history of HIV risk factors should be

elicited.

3. Failure of oral candidiasis

to respond to topical antifungal agents may suggest an immune deficiency.

|

|

Oral Herpes Simplex Virus (Cold Sores)

Associated Clinical Features

Oral herpes simplex may present

acutely as a primary gingivostomatitis or as a recurrence. Painful

vesicular eruptions on the oral mucosa, tongue, palate, vermilion borders,

and gingiva are highly characteristic (Figs. 6.30, 6.31). A 2- to 3-day

prodromal period of malaise, fever, and cervical adenopathy is common.

The vesicular lesions rupture to form a tender ulcer with yellow crusting

and an erythematous margin. Pain may be severe enough to cause drooling

and odynophagia, which can discourage eating and drinking, particularly

in children. The disease tends to run its course in a 7- to 10-day period

with resolution of the lesions without scarring. Recurrent herpes labialis

may present with an aura of burning, itching, or tingling prior to

vesicle formation. Oral trauma, sunburn, stress, and any variety of

febrile illnesses can precipitate this condition.

|

|

|

|

|

Herpes

Simplex Virus (HSV) Stomatitis

Note the vermilion border and lingual lesions that are common in this

condition. A prodromal period of fever, malaise, and cervical

adenopathy may herald the onset of these painful ulcerations.

(Courtesy of James F. Steiner, DDS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HSV

Stomatitis Extensive vesicular

lesions along the vermilion border and surrounding tissues are

consistent with HSV infection. (Courtesy of Frank Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Oral erythema multiforme or

Stevens-Johnson syndrome, aphthous lesions, oral pemphigus, and

hand-foot-mouth (HFM) syndrome are in the differential diagnosis. It

should be noted that aphthous ulcers tend to occur on movable oral mucosa

and rarely on immovable mucosa (i.e., hard palate and gingiva). The

vermilion border is a characteristic location for herpes labialis as

opposed to aphthous lesions. Posterior oropharyngeal ulcerations with

associated hand and foot lesions help to define HFM syndrome. Painful

hemorrhagic oral ulcers in association with anorectal and conjunctival

lesions aid in identifying erythema multiforme or Stevens-Johnson

syndrome. Oral pemphigus is commonly found in elderly patients. Cutaneous

skin bullae and several weeks of vague constitutional symptoms are also

characteristic of pemphigus. A thorough history is invaluable in

differentiating the aforementioned disorders.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Supportive care with rehydration

and pain control are the mainstays of therapy. Temporary pain relief may

be achieved with topical analgesics. Viscous lidocaine, 2%, may be used

as an oral rinse, 5 mL every 3 to 4 h. Oral antiviral agents may be

useful in adults with primary infections. Topical acyclovir ointment may

also be of use by preventing viral spreading and acting as a lubricant to

prevent lip cracking and bleeding. Secondary infection of herpetic

lesions should be treated with oral penicillin or erythromycin.

Clinical Pearls

1. Oral herpetic lesions tend

to occur on the vermilion border, gingiva, and hard palate.

2. Fatal viremia and systemic

involvement may occur in infants and children with herpetic

gingivostomatitis.

3. Primary acute oral herpetic

infection occurs most commonly in children and young adults.

4. Corticosteroid use is

contraindicated in herpetic gingivostomatitis because of potential

worsening of the condition.

|

|

Aphthous Ulcers (Canker Sores)

Associated Clinical Features

Aphthous ulcers are painful

mucosal lesions varying in size from 1 to 15 mm. A prodromal burning

sensation in the affected area may be noted 2 to 48 h before an ulcer is

noted. The initial lesion is a small white papule that ulcerates and

enlarges over the subsequent 48 to 72 h (Fig. 6.32). The lesions are

typically round or ovoid with a raised yellow border and surrounding

erythema. Multiple aphthous ulcers may occur on the lips, tongue, buccal

mucosa, floor of the mouth, or soft palate (Fig. 6.33). Spontaneous

healing of lesions occurs in 7 to 10 days without scarring. The exact

etiology of aphthous lesions is unknown. Deficiencies of vitamin B12,

folic acid, and iron as well as viruses have been implicated. Stress,

local trauma, and immunocompromised states have all been cited as

possible precipitating factors.

|

|

|

|

|

Aphthous

Ulcer (Single Lesion) Raised

yellow borders with surrounding erythema are typical of aphthous

ulcers. (Courtesy of James F. Steiner, DDS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aphthous

Ulcerations Note the multiple

ulcers of various sizes located on the lip and gingival mucosa. These

lesions rarely occur on the immobile oral mucosa of the gingiva or

hard palate. (Courtesy of James F. Steiner, DDS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Primary or recurrent herpetic

oral lesions may present with an almost identical prodrome and similar

appearance to aphthous ulcerations. Herpetic lesions, unlike aphthous

ones, tend to occur on the gingiva, hard palate, and vermilion border.

Oral erythema multiforme may also present similarly to aphthous

stomatitis; however, like oral herpes, it may tend to present with

multiple vesicles in the early stages. Stevens-Johnson syndrome

represents a severe form of erythema multiforme characterized by

hemorrhagic anogenital and conjunctival lesions as well as oral lesions.

Herpangina results from coxsackie and echoviruses with oral ulcerations

typically involving the posterior pharynx. Oral pemphigus should also be

considered in the differential. Behçet's syndrome can present with

recurrent oral lesions, genital ulcers and uveitis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Supportive care, rehydration, and

pain control constitutes the focus of therapy. A topical anesthetic agent

such as 2% viscous lidocaine as an oral rinse every 3 to 4 h is

palliative. Oral rinses containing antihistamines and liquid antacid

mixtures provide comfort. Use of oral antimicrobial rinses containing 0.12%chlorhexidine

(Peridex) or tetracycline is effective in promoting healing. Protective

dental paste (Orabase) may be applied every 6 h to prevent irritation of

lesions. Triamcinolone acetonide in an emollient dental paste applied

three to four times daily may also reduce pain and promote healing of the

lesions.

Clinical Pearls

1. Aphthous ulcers may be

associated with Crohn's disease.

2. Women are more commonly

affected by aphthous lesions than men.

3. The first aphthous episode

occurs most commonly in the second decade of life.

4. Aphthous lesions almost

never occur on the gums or hard palate.

|

|

Strawberry Tongue

Associated Clinical Features

Reddened, hypertrophied lingual

papillae, called strawberry tongue, is associated primarily with scarlet

fever, which is caused by group A streptococcus. The tongue initially

appears white with the erythematous papillae sticking through the white

exudate. After several days, the white coating is lost and the tongue

appears bright red (Fig. 6.34). Other signs of group A streptococcal

infection include fever, an exudative pharyngitis, a scarlatiniform rash,

and the presence of Pastia's lines (petechial linear rash in the skin

folds (see Fig. 14.30)).

|

|

|

|

|

Strawberry

Tongue Note the white exudate

with bulging red papillae. The white coating is eventually lost after

several days, and the tongue then appears bright red. (Courtesy of

Michael J. Nowicki, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Kawasaki syndrome may also

present with an injected pharynx and an erythematous strawberry-like

tongue. It is essential to make the distinction between streptococcal

infection and Kawasaki syndrome, since the latter is associated with a

high incidence of coronary artery aneurysm if left untreated. Also

consider toxic shock syndrome (TSS), in which one-half to three-fourths

of patients tend to have pharyngitis with a strawberry-red tongue.

Patients with TSS also have skin rashes, as with scarlet fever; however,

the rash in TSS is macular and "sunburn-like." Erythema

multiforme can also be associated with fever, pharyngeal erythema, and

lingual lesions; however, it has a more distinct pathognomonic cutaneous

rash (called target or iris lesions).

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Penicillin or a macrolide is the

drug of choice for group A streptococci. Pharyngeal cultures are useful

for confirming the diagnosis. Antistreptolysin O (ASO) titers can be used

for confirmation in the convalescent stage if the diagnosis is in

question. Rapid streptococcal immunoassay testing may help expedite the

diagnosis.

Clinical Pearls

1. A coarse, palpable,

sandpaper-like rash of the skin is highly characteristic of scarlet

fever.

2. Strawberry tongue initially

appears white in color, with prominent red papillae bulging through the

white exudate. After several days, the tongue becomes completely beefy

red.

3. Erythrogenic toxin

elaborated by the streptococcal organism is responsible for producing the

exanthem and enanthem of scarlet fever.

|

|

Torus Palatinus

Associated Clinical Features

Tori are benign nodular

overgrowths of the cortical bone. Although their physical appearance can

be somewhat alarming to those unfamiliar with this entity, there is

generally no need for concern. These bony protuberances occur in the

midline of the palate where the maxilla fuses (Fig. 6.35). Tori may also

be located on the mandible, typically on the lingual aspect of the molar

teeth. Tori are covered by a thin epithelium, which is easily traumatized

and ulcerated. These ulcerations tend to heal very slowly because of the

poor vascularization of the tori. Torus palatinus, in particular, is

slow-growing and may occur at any age; however, it is most commonly noted

prior to age 30 in adults. Torus palatinus affects women twice as

frequently as men.

|

|

|

|

|

Torus

Palatinus Note the nodular

appearance and characteristic central palatal location. Abrasions and

ulcerations can occur on the thin overlying epithelium secondary to

trauma by food and oral objects. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD,

MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

There are a variety of oral

conditions that may be confused with mandibular or palatal tori. Gingival

fibromatosis, fibroma formation secondary to irritation, granulomas,

abscesses, and oral neurofibromatosis located on the palate may all be

similar in appearance to torus palatinus. Nodular bony enlargement in the

oral cavity may also result from fibrous dysplasia, osteomas, and Paget's

disease. Oral malignancies may also manifest themselves on the palate as

primary lesions. Biopsies, oral radiographs, and CT scans may aid in

differentiating these conditions.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Tori are normal structural

variants and do not represent any inflammatory or neoplastic process.

Therefore, they are of no clinical significance and require no treatment

unless associated with a complication. Tori may enlarge enough to

interfere with eating or speaking and impair proper fitting of dental

prosthesis. For some patients the mere presence of torus palatinus may be

bothersome and undesirable. Oral and maxillofacial consultation is

indicated for suspected malignancies or lesions of questionable origin.

Clinical Pearls

1. Torus palatinus almost

always occurs in the midline of the hard palate.

2. Both torus palatinus and

torus mandibularis are nontender and otherwise asymptomatic.

|

|

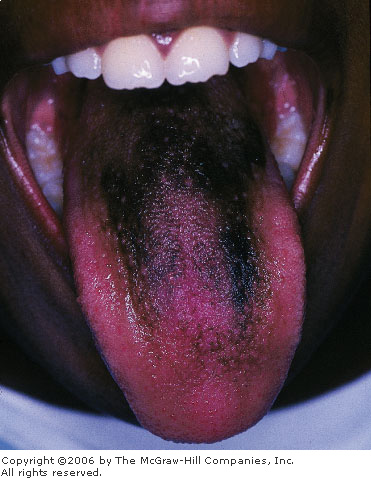

Black Hairy Tongue

Associated Clinical Features

Black hairy tongue represents a

benign reactive process characterized by hyperplasia and dark

pigmentation of the tongue's filiform papillae (Fig. 6.36). The elongated

filiform papillae may reach up to 2 cm in length and vary in actual

degree of pigmentation from light tan to black. Predisposing factors may

include excessive smoking, poor oral hygiene, and the use of

broad-spectrum oral antibiotics. Pigment from consumed food, beverages,

and tobacco products stains the entrapped food debris and desquamated

papillary keratin. Some antibiotics may alter normal oral microflora and

promote the growth of chromogenic organisms, also contributing to the

tongue's discoloration. The darkly pigmented filament-like papillae give

the tongue a black, hairy appearance. Males are more often affected than

females; this condition very rarely occurs in children. Alteration of

taste perception and halitosis may be a consequence of this disorder.

|

|

|

|

|

Black

Hairy Tongue Hyperplasia of

the filiform papillae on the dorsum of the tongue accompanied by deposition

of dark pigment is characteristic of black hairy tongue. (Courtesy of

the Department of Dermatology, National Naval Medical Center,

Bethesda, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Geographic tongue and orolingual

candidiasis may resemble more lightly pigmented forms of black hairy

tongue (BHT). Similarly, dark discoloration of normal tongue papillae may

also mimic BHT clinically. This exogenous pigmentation of normal papillae

may come from ingested food dyes and certain medications, such as

bismuth-containing compounds (Fig. 6.37), ketoconazole, and

azidothymidine. The lack of hyperplastic filiform papillae with

additional pigmentation of other oral mucosal surfaces may aid in

distinguishing these conditions.

|

|

|

|

|

Black

Tongue Deposition of black

pigment secondary to bismuth ingestion. This patient ingested

Pepto-Bismol. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Improved oral hygiene with gentle

tongue brushing and a reduction in the ingestion of exogenous

pigment-containing substance represent the cornerstone of treatment.

Removal of other predisposing factors (e.g., antibiotic withdrawal and

smoking cessation) will also promote resolution of this condition. The

use of topically applied retinoid preparations and antifungal agents has

been advocated for more refractory instances.

Clinical Pearls

1. BHT always involves the

dorsal aspect of the tongue anterior to the circumvallate papillae.

2. This is a benign condition

and is rarely symptomatic.

3. The tongue is not always

black and can be as light as a tan or yellow color.

|

|

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Sara-Jo

Gahm, MD, for portions of this chapter written for the first edition of

this book.

|

|