|

Note: Large images and

tables on this page may necessitate printing in landscape mode.

Copyright

©2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved.

Emergency

Medicine Atlas > Part 1. Regional

Anatomy > Chapter 7. Chest and Abdomen > Chest

and Abdominal Trauma >

|

Traumatic Asphyxia

Associated Clinical Features

Traumatic asphyxia is due to a

sudden increase in intrathoracic pressure against a closed glottis. The

elevated pressure is transmitted to the veins, venules, and capillaries

of the head, neck, extremities, and upper torso, resulting in capillary

rupture. Survivors demonstrate plethora, ecchymoses, petechiae (Figs. 7.1

and 7.2), and subconjunctival hemorrhages. Severe cases may produce CNS

injury with seizures, posturing, and paraplegia.

|

|

|

|

|

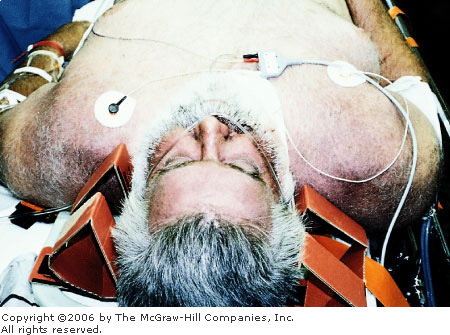

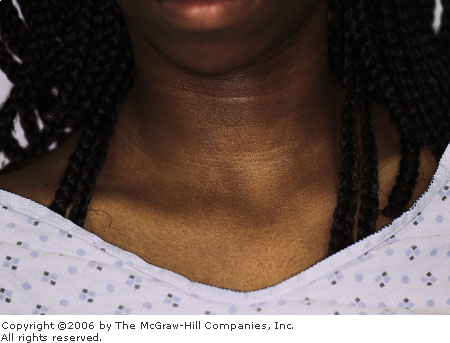

Traumatic

Asphyxia This 45-year-old male

was pinned when the truck he was working under fell on his chest. He

was unable to breathe for 3 to 4 min until his coworkers rescued him.

The violaceous coloration of the shoulders, face, and upper chest is

apparent. (Courtesy of Stephen Corbett, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

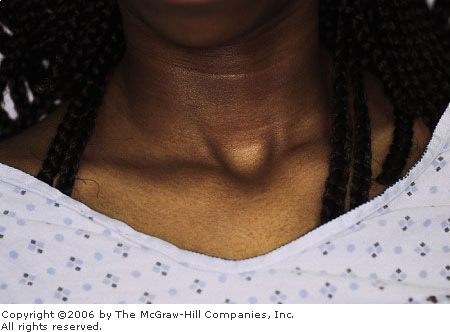

Traumatic

Asphyxia A closer view showing

the petechial nature of this rash. The patient was observed in the

hospital overnight and recovered completely. (Courtesy of Stephen

Corbett, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Sudden traumatic compression of

the superior vena cava produces obstruction similar to that seen in the

superior vena cava syndrome. Both demonstrate a violaceous discoloration

of the face and neck. History will confirm the diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment is supportive, with

attention to other concurrent injuries. Long-term morbidity is related to

the associated injuries.

Clinical Pearls

1. Facial petechiae are known

as Tardieu's spots.

2. Be alert for associated rib

and vertebral fractures.

|

|

Tension Pneumothorax with Needle Thoracentesis

Associated Clinical Features

A tension pneumothorax results

when air is able to enter but not exit the pleural space. Air in the

pleural space accumulates and compresses the ipsilateral lung and vena

cava, with a rapid decrease in cardiac output. The contralateral lung may

suffer ventilation/perfusion ( / / )

mismatch. Subcutaneous air, tracheal deviation, jugulovenous distention

(JVD), and diminished or hyperresonant ipsilateral breath sounds can be

clues. Subcutaneous emphysema may be visible on the neck and chest and is

easily diagnosed by palpation. The released air from a tension

pneumothorax can be heard escaping from a needle thoracostomy. )

mismatch. Subcutaneous air, tracheal deviation, jugulovenous distention

(JVD), and diminished or hyperresonant ipsilateral breath sounds can be

clues. Subcutaneous emphysema may be visible on the neck and chest and is

easily diagnosed by palpation. The released air from a tension

pneumothorax can be heard escaping from a needle thoracostomy.

Differential Diagnosis

Cardiac tamponade, congestive

heart failure with pulmonary edema, esophageal intubation, and

anaphylaxis should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment requires rapid recognition

of the tension pneumothorax, frequently without benefit of chest

radiographs. A large-bore needle (at least 14 gauge) should be placed

over the superior rib surface of the second interspace in the

midclavicular line (Fig. 7.3). A rush of air with improvement of vital

signs confirms the diagnosis. A syringe loaded with sterile saline allows

visualization of air return but is not mandatory. If there is no

immediate improvement, do not hesitate to place a second needle in the

next interspace. A chest tube should be placed as soon as possible.

Ventilation with appropriate inspiratory/expiratory ratio would prevent

further occurrences.

|

|

|

|

|

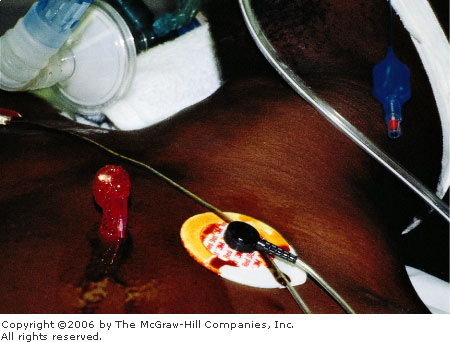

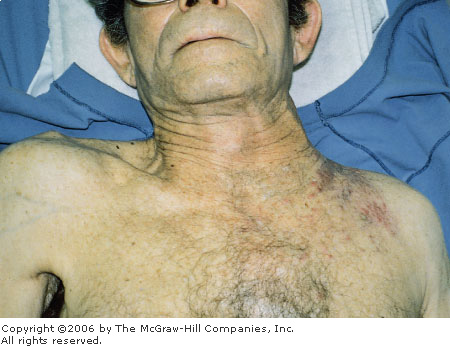

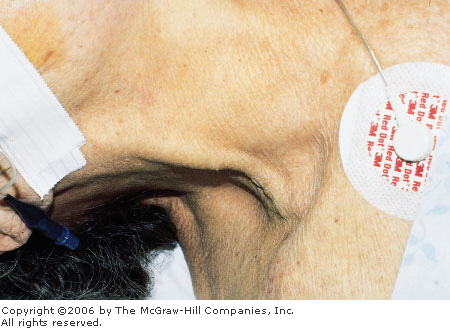

Tension

Pneumothorax A 35-year-old

male with severe asthma suffered respiratory arrest during transport

by ambulance. He was intubated on arrival but soon became hard to

ventilate and developed subcutaneous emphysema followed by hypotension.

Needle thoracostomy produced a rush of air and bubbling from the

needle with stabilization of vital signs. (Courtesy of Stephen

Corbett, MD.)

|

|

Clinical Pearls

1. Do not overventilate

patients with obstructive pulmonary disease. "Stacking" breaths

trap air in the lungs and predispose to bleb rupture and pneumothorax.

The pathophysiology of this disease requires a prolonged expiratory

phase.

2. The diagnosis of a tension

pneumothorax is made clinically and should be treated immediately with a

needle thoracostomy and ultimately a tube thoracostomy.

|

|

Cardiac Tamponade with Pericardiocentesis

Associated Clinical Features

Beck's triad of acute cardiac

tamponade includes jugulovenous distention (JVD) from an elevated central

venous pressure (CVP), hypotension, and muffled heart sounds. In trauma,

only one-third of patients with cardiac tamponade demonstrate this

classic triad, although 90% have at least one of the signs. The

simultaneous appearance of all three physical signs is a late

manifestation of tamponade and usually seen just prior to cardiac arrest.

Other symptoms include shortness of breath, orthopnea, dyspnea on

exertion, syncope, and symptoms of inadequate perfusion.

Differential Diagnosis

Patients with a chronic

pericardial effusion have an elevated CVP and a small, quiet heart but

are relatively asymptomatic and without hypotension.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The clinical diagnosis of

tamponade requires suspicion and a careful evaluation of the signs and,

when available, imaging techniques. Two-dimensional echocardiography

represents the ultimate standard for diagnosis. ED pericardiocentesis

(Fig. 7.4) is a diagnostic and resuscitative procedure in patients with

suspected cardiac tamponade. Goals of ED pericardiocentesis include

identification of pericardial effusion and removal of blood from the

pericardial space to relieve the tamponade.

|

|

|

|

|

ED

Pericardiocentesis A positive

pericardiocentesis in a patient with a sudden onset of shortness of

breath and electrical alternans. (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

Clinical Pearls

1. An electrical alternans seen

on a 12-lead ECG suggests pericardial effusion.

2. Beck's triad for acute

cardiac tamponade is a late manifestation and is seen in only 30% of

trauma patients.

|

|

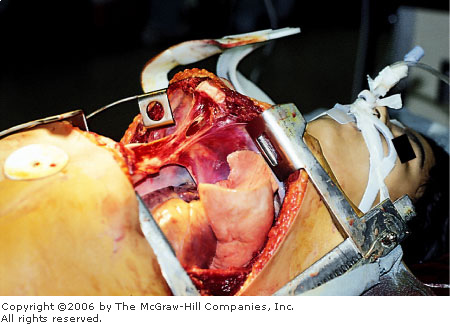

Emergency Department Thoracotomy

Associated Clinical Features

ED thoracotomy is a resuscitative

procedure performed in patients with penetrating chest trauma who have

lost signs of life in the presence of prehospital or ED personnel.

Resuscitative thoracotomy (Fig. 7.5) in the ED has specific goals once

the chest is opened: relief of cardiac tamponade, support of cardiac function

(internal cardiac compressions, cross-clamping the aorta to improve

coronary perfusion, and internal defibrillation), and control of

hemorrhage from the heart, pulmonary vessels, thoracic wall, and great

vessels.

|

|

|

|

|

ED

Thoracotomy An unsuccessful

resuscitative ED thoracotomy with pericardiotomy in a patient with

penetrating chest trauma who lost signs of life in the field after

the paramedics arrived at the scene. (Courtesy of Alan B. Storrow,

MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Few conditions present that

require immediate ED thoracotomy. A trauma patient who has lost vital

signs prior to arrival of prehospital personnel is deceased and not a

candidate for this procedure.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Patients with penetrating

thoracic trauma who lose their vital signs en route to the ED should

receive an immediate thoracotomy on arrival by the most experienced

provider. Patients with penetrating thoracic trauma whose blood pressure

cannot be maintained above 70 mmHg with aggressive fluid and blood

management should be considered for ED thoracotomy. Patients with blunt

trauma who lose their vital signs en route to the ED should not undergo

an ED thoracotomy, since they rarely survive. Surgical support should be

notified as soon as possible.

Clinical Pearls

1. Injuries potentially

responsive to resuscitative ED thoracotomy include cardiac tamponade,

pulmonary parenchymal and tracheobronchial injuries, large-vessel

injuries, air embolism, and penetrating heart injuries.

2. Resuscitative ED thoracotomy

should be performed immediately once the indications have been met, since

the likelihood of survival is greater when this is performed earlier in

the resuscitation.

|

|

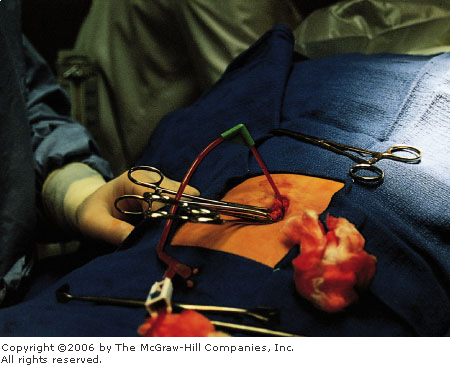

Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage (DPL)

Associated Clinical Features

Diagnostic peritoneal lavage

(DPL) was introduced in 1965 as a simple, fast, and reliable technique to

identify hemoperitoneum in patients with blunt and penetrating abdominal

trauma. It is performed by placing a catheter into the peritoneum,

aspirating for gross blood, and introducing 1 L of crystalloid if the

initial aspiration is negative (Fig. 7.6). The lavage fluid is then withdrawn

and white and red cell blood counts are obtained. Interpretation of the

results is based on the type of trauma. A "grossly positive"

DPL is evident when 10 mL of blood is obtained on the initial aspiration.

The procedure is considered positive in blunt abdominal trauma when

>100,000 RBC/mm3 or >500 WBC/mm3 are present

in the lavage fluid. In penetrating abdominal trauma, the procedure is

considered positive when >10,000 RBC/mm3 are present (up to

100,000 RBC/mm3 is used by some). Lavage fluid containing

intestinal contents is evidence of perforating bowel injury.

|

|

|

|

|

Positive

DPL DPL fluid obtained from

this patient with blunt trauma was microscopically positive. Initial

aspiration was negative. (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Indications for DPL in blunt

trauma include equivocal examination with significant abdominal trauma,

unreliable examination (intoxication, spinal trauma, head injury),

unexplained hypotension with suspected abdominal injury, and when serial

examinations are not possible (in patients going to the operating room

for other injuries).

Indications for DPL in

penetrating trauma include patients in whom the need for celiotomy is

unclear, tangential wounds in which peritoneal penetration is uncertain,

stab wounds in which there are no peritoneal signs or signs of peritoneal

penetration, and low chest wounds to identify diaphragmatic injury.

Contraindications to DPL include

any condition in which a celiotomy is clearly indicated, since this would

delay definitive treatment.

Differential Diagnosis

Injuries that may not be

diagnosed with DPL include subcapsular liver or spleen hematomas, injury

to a hollow viscus, ruptured diaphragm, and ruptured bladder.

Retroperitoneal injuries (pancreatic, duodenal) are not diagnosed with

DPL.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

A positive DPL is an indication

for celiotomy. Patients with negative DPLs are observed or discharged

based on a variety of factors including injury mechanism, comorbid

disease states, and concurrent traumatic injuries.

Clinical Pearls

1. Intraperitoneal blood (30

mL) will typically give a DPL result of  100,000

RBC/mm3. 100,000

RBC/mm3.

2. Controversy exists over the

positive cell count in penetrating abdominal trauma, since the range for

a positive result can vary between centers from 1000 to 100,000 RBC/mm3.

3. If transfer is indicated, a

sample of DPL fluid should accompany the patient.

|

|

Seat Belt Injury

Associated Clinical Features

Seat belts have reduced mortality

and the severity of trauma due to motor vehicle accidents; however, they occasionally

produce injury. Injuries caused by the standard three-point restraint

harness (Fig. 7.7) are most commonly rib fractures. Injuries caused by

the older lap belts include abdominal injuries such as bowel contusion or

perforation and lumbar fractures.

|

|

|

|

|

Seat

Belt Injury Ecchymosis from

the three-point seat belt is clearly seen. The injuries identified

are multiple rib fractures and multiple hematomas of the small bowel

wall. (Courtesy of Stephen Corbett, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

A careful primary and secondary

survey identifies most injuries caused by seat belt use. Difficult

diagnosis occurs in the case of bowel perforation or diaphragmatic

rupture, in which signs and symptoms may not occur until hours or days

after the initial injury.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Patients with a mechanism for

significant trauma or with other injuries requiring admission should be

admitted for observation or definitive treatment. Patients discharged

home from the ED should be given appropriate precautions to monitor for a

delayed injury presentation.

Clinical Pearls

1. Maintain a high suspicion

for intraabdominal injury when ecchymosis from a seat belt is seen in a

trauma victim.

2. When lap belt bruises are

present, there is a higher incidence of bowel injury.

|

|

Grey-Turner's Sign and Cullen's Sign

Associated Clinical Features

Bluish to purplish periumbilical

discoloration (Cullen's sign) and left flank discoloration (Grey-Turner's

sign) represent retroperitoneal hemorrhage that has dissected through

fascial planes to the skin (Fig. 7.8). Retroperitoneal blood may also

extravasate into the perineum, causing a scrotal hematoma or inguinal

mass. This hemorrhage may represent a hemodynamically significant bleed.

|

|

|

|

|

Grey-Turner's

and Cullen's Signs This

patient displays both flank and periumbilical ecchymoses

characteristic of Grey-Turner's and Cullen's signs. (Courtesy of

Michael Ritter, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Cullen's sign and Grey-Turner's

sign are most frequently associated with hemorrhagic pancreatitis (seen

in 1 to 2% of cases), and typically are seen 2 to 3 days after onset of

acute pancreatitis. These signs may also be seen in ruptured ectopic

pregnancy, severe trauma, leaking or ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm,

coagulopathy, or any other condition associated with bleeding into the

retroperitoneum.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment of patients with

Grey-Turner's sign or Cullen's sign depends on the etiology of the

hemorrhage. Because the hemorrhage may represent a hemodynamically

significant bleed, cardiovascular stabilization after airway

stabilization is of the utmost importance. Once the patient has been

stabilized, the source of bleeding can be elicited by selected laboratory

[complete blood cell count (CBC), amylase, lipase, human chorionic

gonadotropin (HCG)] and diagnostic studies [ultrasound, computed

tomography (CT)]. Because of the severity of diseases associated with

Grey-Turner's and Cullen's signs, these patients are usually admitted to

the hospital.

Clinical Pearls

1. Grey-Turner's sign (flank

discoloration) and Cullen's sign (periumbilical discoloration) are due to

retroperitoneal bleeding that has dissected through fascial planes.

2. These signs are typically

seen 2 to 3 days after the acute event.

3. These signs are seen in only

1 to 2% of patients with hemorrhagic pancreatitis.

|

|

Impaled Foreign Body

Associated Clinical Features

Stab wounds cause injury to

tissue in their path. Stab wounds to the chest, in addition to causing

pneumo- or hemothorax, may also cause life-threatening injuries to the

heart and major blood vessels (Fig. 7.9). One-third of stab wounds to the

abdomen (Fig. 7.10) penetrate the peritoneal cavity. Half of those

injuries that penetrate the peritoneum require surgical intervention. The

path of the stab wound is difficult to determine if the inflicting object

has been removed. The size of the external wound frequently

underestimates the internal injury. Impaled foreign bodies to the chest

or abdomen pose a complex problem. The object inflicting the injury may

also be preventing significant blood loss and therefore should be removed

by the trauma surgeon in the operating room.

|

|

|

|

|

Impaled

Chest Wound This patient was

stabbed in the chest with a butcher knife in a family dispute. The

knife was stabilized by EMS providers at the scene and removed in the

operating room. Injury was isolated to the right atrium. (Courtesy of

Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Impaled

Abdominal Foreign Body Impaled

knife to the left abdomen. (Courtesy of Ian Jones, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Determining whether the impaled

object has violated the peritoneum or if injury to a significant

structure has occurred can be determined by local wound exploration or

diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL), depending on the stability of the

patient and location of the wound (see Fig. 7.13).

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Initial stabilization of the

patient (intravenous fluid resuscitation, oxygen, monitoring), obtaining

appropriate laboratory studies including blood type and cross-matching,

and resource mobilization (trauma team) are important steps in the

initial management of penetrating chest or abdominal trauma. Prior to

surgical evaluation, stabilization of the impaled foreign object should

be performed to prevent further injury.

Clinical Pearl

1. Impaled chest or abdominal

foreign bodies should be removed only by the trauma surgeon in a

controlled setting.

|

|

Abdominal Evisceration

Associated Clinical Features

Evisceration of abdominal

contents (Fig. 7.11) usually occurs after a stab or slash wound to the

abdomen (Fig. 7.12). It is an indication for celiotomy (laparotomy).

Other indications for celiotomy in penetrating abdominal trauma include

peritoneal injury; unexplained shock; evidence of blood in the stomach,

bladder, or rectum; and loss of bowel sounds.

|

|

|

|

|

Abdominal

Evisceration Self-induced

evisceration with bowel perforation and spillage of food particles is

clearly seen in this photograph. This patient went directly to the

operating room. (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abdominal

Evisceration Evisceration of

small bowel after assault and stab wound to the right lower abdomen.

(Courtesy of Frank Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Superficial laceration without

peritoneal penetration, laceration with peritoneal penetration but no

visceral injury, and laceration with peritoneal penetration and visceral

injury may present with a similar mechanism and need to be

differentiated. Consideration of the anatomic boundaries of the abdomen

(Fig. 7.13) is important in differentiating abdominal injuries from

penetrating chest or retroperitoneal injuries.

|

|

|

|

|

Anatomic

Boundaries of the Abdomen Anterior

abdomen: Anterior costal

margins superiorly, laterally by the anterior axillary lines, and

inferiorly by the inguinal ligaments.

Low

chest: Nipple line (fourth

intercostal space) anteriorly and inferior scapular tip (seventh

intercostal space) to inferior costal margins.

Flank: (Shaded blue) Anterior axillary line

anteriorly, posteriorly by the posterior axillary line, inferiorly by

the iliac crest, and superiorly by the inferior scapular tip. The

back is bounded laterally by the posterior axillary lines.

Back: Inferior scapular tip to iliac crest and

posterior axillary lines.

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Initial stabilization

(intravenous fluid resuscitation, oxygen, and monitoring), obtaining

appropriate laboratory studies including a blood type and cross-matching,

and resource mobilization (notifying surgical team, operating room, and

anesthesiology) are important steps in the initial management of

penetrating abdominal trauma. In most cases, definitive treatment is

celiotomy.

Clinical Pearls

1. Indications for celiotomy

after penetrating wounds to the abdomen include evisceration; peritoneal

signs; unexplained hypotension; blood in the stomach, bladder, or rectum;

and loss of bowel sounds.

2. Selected patients with stab

wounds to the abdomen and peritoneal penetration may be conservatively

observed for delayed complications.

3. As many as 20% of patients

with stab wounds to the abdomen can be discharged from the ED based on a

negative wound exploration.

|

|

Traumatic Abdominal Hernia

Associated Clinical Features

Blunt traumatic abdominal hernia

is defined as herniation through disrupted musculature and fascia

associated with adequate trauma, without skin penetration, and no

evidence of a prior hernial defect at the site of injury (Fig. 7.14).

This occurs when a considerable blunt force is distributed over a surface

area large enough to prevent skin penetration but small enough to cause a

focal defect in the underlying fascia or muscle wall. Most of these

injuries are due to seat belt injures in motor vehicle crashes; handlebar

injuries are the second most common cause.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Traumatic

Abdominal Wall Hernia This

5-year-old boy suffered a traumatic hernia from a handlebar injury.

(Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Existing hernia, abdominal wall

hematoma, and abdominal wall contusion should be considered in evaluating

a patient with focal blunt trauma to the abdomen and possible hernia.

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) with contrast is the diagnostic

procedure of choice in the evaluation of abdominal trauma (Fig. 7.15).

Ultrasound may play a limited role in the diagnosis of abdominal wall

hernia.

|

|

|

|

|

CT

Scan, Abdominal Wall Hernia

Abdominal contents are seen extruding through a fascial defect.

(Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Identification and treatment of

life-threatening associated injuries takes priority over the hernia. The

hernial defect should be repaired after the patient has been stabilized.

Clinical Pearls

1. Abdominal hernia due to

blunt trauma is a rare injury, most frequently due to seat belt injuries

in motor vehicle crashes.

2. CT scan is the diagnostic

procedure of choice for abdominal wall hernia.

|

|

Respiratory Retractions

Associated Clinical Features

Increased respiratory effort may

be manifest by increased respiratory rate, increased chest wall

excursion, and retractions of the less rigid structures of the thorax.

Retractions of the sternum (Fig. 7.16), suprasternal notch (Fig. 7.17),

and intercostal retractions reflect increased respiratory effort. This

may be due to obstructive disease such as asthma or tracheal obstruction,

pneumonia, or restrictive disease. The presence of stridor, wheezing, or

rhonchi will help distinguish the cause.

|

|

|

|

|

Sternal

Retractions Sternal

retractions in a patient with croup. (Courtesy of Stephen Corbett,

MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Suprasternal

Retractions Suprasternal

retractions in an adolescent with severe asthma. (Courtesy of Kevin

J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Asthma, chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease, emphysema, epiglottitis, croup, foreign-body

aspiration, esophageal foreign body, bacterial tracheitis, posterior

pharyngeal abscess, and anaphylaxis are all conditions that must be

considered in a patient with retractions.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

An aggressive search for the

cause of the retractions is required to direct therapy. Rapid evaluation

of the airway for patency and breathing for oxygenation should be done

immediately on presentation. High-flow oxygen by face mask is appropriate

for patients in respiratory distress. Preparations for securing an airway

should be underway for those patients in severe distress or respiratory

failure. Routine measures for the mildly symptomatic patient depend on

the cause of the retractions. For asthma or exacerbations of chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), nebulized  2

agonists and steroid therapy may be appropriate. Patients with croup may

require nebulized normal saline and possibly epinephrine or dexamethasone

as initial therapy. Foreign-body aspiration requires consultation for

confirmation of the suspected diagnosis and removal. 2

agonists and steroid therapy may be appropriate. Patients with croup may

require nebulized normal saline and possibly epinephrine or dexamethasone

as initial therapy. Foreign-body aspiration requires consultation for

confirmation of the suspected diagnosis and removal.

Clinical Pearls

1. Retractions are best

observed with the patient at rest with the chest exposed.

2. Retractions from obstructive

airway disease can be intercostal and supraclavicular and are usually

accompanied by nasal flaring, increased expiratory phase, and increased

respiratory rate.

|

|

Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

Associated Clinical Features

This symptom complex develops

from obstruction of venous drainage from the upper body, resulting in

increased venous pressure, which leads to dilation of the collateral

circulation. Superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome is most commonly caused by

malignant mediastinal tumors. Dyspnea; swelling of the face, upper

extremities, and trunk; chest pain, cough, or headache may be present.

Physical findings include dilation of collateral veins of the trunk and

upper extremities, facial edema and erythema (plethora), cyanosis, and

tachypnea (Fig. 7.18).

|

|

|

|

|

Superior

Vena Cava Syndrome A

27-year-old man with SVC syndrome. Note the prominent collateral

veins of the chest and neck. (Courtesy of William K. Mallon, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Malignancy, pericarditis,

pericardial tamponade, tuberculosis, and congestive heart failure should

be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Radiation therapy is the

treatment of choice for most malignant mediastinal tumors causing SVC

syndrome. Administration of corticosteroids and diuretics initiated in

the ED may provide temporary relief pending definitive therapy.

Clinical Pearls

1. SVC syndrome is most

commonly caused by malignant mediastinal tumors.

2. Treatment of most

mediastinal tumors causing SVC syndrome is radiation therapy.

3. CT scan of the chest is the

diagnostic modality of choice for patients with SVC syndrome.

|

|

Apical Lung Mass

Associated Clinical Features

Pancoast's tumor involves the

apical lung and may affect contiguous structures such as the brachial

plexus, sympathetic ganglion, vertebrae, ribs, superior vena cava, and

recurrent laryngeal nerve (more common for left-sided tumors). Horner's

syndrome, extremity edema, nerve deficits, hoarseness, and superior vena

cava syndrome may result. Erosion of tumor through the chest wall can

cause compression of venous outflow, with resultant jugulovenous

distention (JVD) (Fig. 7.19).

|

|

|

|

|

Apical

Lung Mass This 68-year-old

male cigarette smoker complained of cough and weight loss. A chest

radiograph shows a left apical tumor. There is erosion of the tumor

into the chest wall, with an indurated supraclavicular and

infraclavicular mass. Moderate JVD is apparent, suggesting venous

outflow obstruction. (Courtesy of Stephen Corbett, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Virchow's node of abdominal

carcinoma, lymphoma, vascular abnormalities, and tuberculosis should be

considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment depends on the staging

and type of tumor. The superior vena cava syndrome can be treated acutely

with radiation and diuretics. Thrombolytic therapy has been used

successfully in some cases of acute vena caval thrombosis.

Clinical Pearls

1. Thrombosis may cause acute

decompensation with edema, plethora, and airway collapse.

2. Prompt radiation therapy can

be lifesaving in cases of vena caval obstruction.

|

|

Jugulovenous Distention

Associated Clinical Features

Central venous (right atrial)

pressure is reflected by distention of the internal or external jugular

veins. Normal pressure is less than 3 cm of distention above the sternal

angle of Louis. Distention greater than 4 cm should be considered

abnormal. Evaluation begins by raising the head of the supine patient 30

to 60 degrees. The highest point of venous pulsation at the end of normal

expiration is measured from the sternal angle of Louis. The presence of

jugulovenous distention (JVD) (Fig. 7.20) should prompt an immediate

search for possible pulmonary or cardiac pathology. The presence of

crackles, murmurs, rubs, percussed hyperresonance, or crepitus may help

disclose the etiology.

|

|

|

|

|

Jugulovenous

Distention An engorged

external jugular vein is noted as it crosses the sternocleidomastoid

muscle into the posterior triangle of the neck and disappears beneath

the clavicle to join the brachiocephalic vein and the superior vena

cava. This patient has severe congestive heart failure requiring

intubation. (Courtesy of Stephen Corbett, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Causes of JVD include right

ventricular failure, left ventricular failure, biventricular failure,

parenchymal lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonic stenosis,

restrictive pericarditis, superior vena cava syndrome, pulmonary embolus,

tricuspid valve outflow obstruction, tension pneumothorax, increased

circulating blood volume, and atrial myxoma. Temporary venous engorgement

may result from Valsalva maneuver, positive pressure ventilation, and

Trendelenburg position.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment varies depending on the

cause. Preload reduction may help in cases of congestive heart disease.

Reversal of a traumatic etiology with needle thoracostomy or

pericardiocentesis may be required.

Clinical Pearls

1. Right-sided myocardial

infarction may produce JVD with clear lung fields.

2. JVD may be absent in the

presence of the above-listed causes if hypovolemia is present.

|

|

Caput Medusae

Associated Clinical Features

Veins of the abdomen normally are

scarcely visible within the abdominal wall. Engorged veins, however, are

often visible through the normal abdominal wall. Engorged veins forming a

knot in the area of the umbilicus are described as a caput medusae (Fig.

7.21). The extent of associated findings depends on the underlying

etiology. It is usually secondary to liver cirrhosis, with subsequent

portal hypertension and development of circulation circumventing the liver.

|

|

|

|

|

Caput

Medusae This elderly female

with alcoholic cirrhosis has engorged abdominal veins in the knotted

appearance consistent with caput medusae. (Courtesy of Gary Schwartz,

MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Emaciation, inferior vena caval

obstruction, superior vena caval obstruction, portal vein obstruction,

and superficial abdominal vein thrombosis can cause engorged abdominal

veins.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment is directed at the

underlying cause. This finding by itself does not require acute

treatment.

Clinical Pearl

1. Caput medusae has the same

clinical significance as the more common pattern of venous engorgement.

|

|

Abdominal Hernias

Associated Clinical Features

A hernia is a tissue protrusion

through an abnormal body cavity opening. Most abdominal wall hernias

occur at the groin and umbilicus. Incarceration is defined as the inability

to reduce the protruding tissue to its normal position. Strangulation

occurs when the blood supply of the hernia's contents is obstructed and

tissue necrosis ensues. An incisional hernia (Fig. 7.22) may

manifest clinically as a mass or palpable defect adjacent to a surgical

incision and can be reproduced by having the patient perform Valsalva's

maneuver. Obesity and wound infection, which interfere with wound

healing, predispose to the formation of incisional hernias. The defect of

an indirect inguinal hernia (Figs. 7.23, 7.24) is the internal

(abdominal) inguinal ring and may be manifest in either sex by a bulge

over the midpoint of the inguinal ligament that increases in size with

Valsalva's maneuver. A fingertip placed into the external ring through

the inguinal canal may palpate the defect. A direct hernia (Fig.

7.25) may be manifest by a bulge midway adjacent to the pubic tubercle

and may be felt by the pad of the finger placed in the inguinal canal.

The defect is in the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. Direct

inguinal hernias are usually painless and occur in males.

|

|

|

|

|

Incisional

Hernia An incisional hernia in

an obese female. (Courtesy of Stephen Corbett, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Indirect

Inguinal Hernia A recurrent

indirect inguinal hernia in a female patient. (Courtesy of Frank

Birinyi, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Indirect

Inguinal Hernia This

35-year-old man has an incarcerated indirect inguinal hernia (A) with

small bowel obstruction (B). (Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Direct

Inguinal Hernia A direct

inguinal hernia. Note the bulge adjacent to the left pubic tubercle.

(Courtesy of Daniel L. Savitt, MD.)

|

|

Nausea and vomiting may be

present if incarceration with bowel obstruction occurs. Strangulation can

lead to fever, peritonitis, and sepsis.

Differential Diagnosis

Tumor, aneurysm, lymphadenopathy,

bowel obstruction, ascites, lipoma, femoral hernia, hydrocele, testicular

torsion, and epididymitis may have similar presentations.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

When patients present without

clinical evidence of strangulation (fever, leukocytosis, systemic signs

of toxicity), reduction should be attempted. In the presence of these

signs, prompt surgical consultation is warranted for surgical reduction.

Reduction in the ED is facilitated with systemic analgesia (as most

patients present with significant pain), placing the patient in the

supine position, and applying a cold pack to the hernia. Routine

consultation for operative repair is indicated in asymptomatic patients

with reducible hernias.

Clinical Pearls

1. Acutely strangulated or

incarcerated hernias require immediate surgical evaluation.

2. Direct inguinal hernias are

usually painless.

3. Evaluation and treatment of

concomitant exacerbating conditions (cough, constipation, vomiting)

prevent recurrences.

|

|

Umbilical Hernias

Associated Clinical Features

The umbilicus is a common site of

abdominal hernias. Predisposing conditions in adults most commonly

include ascites and prior abdominal surgery. The size of the defect

determines the symptomatology and incidence of incarceration, with

smaller defects resulting in more pronounced symptoms and an increased

incidence of incarceration. Pain is located in the area of the fascial

defect. Contents of the hernia may be palpable and tender. Symptoms of

obstruction (nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distention) may be present.

If the hernia becomes strangulated (Fig. 7.26), erythema of the overlying

skin with fever and hypotension may occur.

|

|

|

|

|

Strangulated

Umbilical Hernia The skin

overlying a strangulated umbilical hernia is erythematous and tender.

(Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

An omphalocele, gastroschisis, or

urachal duct cyst may present as an umbilical mass.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Reduction is attempted in the

stable patient without clinical evidence of strangulation. Treatment of

any predisposing conditions (i.e., abdominal paracentesis in the patient

with tense ascites) may cause spontaneous reduction and avoid progression

of the hernia to strangulation. Routine consultation for elective repair

is indicated in asymptomatic patients with reducible hernias.

Clinical Pearls

1. Umbilical hernias in

children usually resolve without treatment.

2. Umbilical hernias in adults

usually become worse and require elective repair.

|

|

Patent Urachal Duct

Associated Clinical Features

When the vestigial urachal duct

is not obliterated during development, drainage can occur from the bladder

to the umbilicus (Fig. 7.27). Cysts can often be palpated between the

umbilicus and pubis. Besides drainage and pain, infection of the duct or

cyst may occur. Rarely, adenocarcinoma may form in these remnants.

|

|

|

|

|

Patent

Urachal Duct This 19-year-old

man presented to the ED with clear fluid (urine) draining from the

umbilicus, suggestive of a patent urachal duct. (Courtesy of Kevin J.

Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Omphalocele, prune belly

syndrome, exstrophy of the bladder, gastroschisis, and umbilical hernias

are other abdominal wall abnormalities in children.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Acute treatment is usually not

required unless an infection is evident. Routine urologic consultation

for surgical revision is indicated. A retrograde study with radiopaque

dye will outline the patent duct.

Clinical Pearl

1. This finding should prompt a

careful search for other urogenital anomalies.

|

|

Sister Mary Joseph's Node (Nodular Umbilicus)

Associated Clinical Features

A Sister Mary Joseph's node is a

metastasis manifesting as periumbilical lymphadenopathy secondary to

abdominal carcinoma (Fig. 7.28). Cancers of the colon may cause pain,

change in bowel habits, anemia, and obstruction. In general, left-sided

cancers cause obstruction, whereas right-sided tumors may have

significant metastases before they create signs and symptoms. These metastases

typically involve peritoneal and omental spread with distant metastases

to the liver. Spread to the umbilicus is colloquially known as the Sister

Mary Joseph's node.

|

|

|

|

|

Sister

Mary Joseph's Node Sister Mary

Joseph's nodule of patient with gastric carcinoma. (Courtesy of

Department of Dermatology, Naval Medical Center, Portsmouth, VA.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Other umbilical masses to

consider include hernias, ascites, and urachal cysts.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Prompt referral for staging and

treatment of the tumor is indicated. Other signs and symptoms (from

obstruction, blood loss, malnutrition, and pain) should be addressed and

treated.

Clinical Pearls

1. Virchow's node, presenting

as a supraclavicular mass, also heralds bowel carcinoma.

2. A Sister Mary Joseph's node

is commonly due to gastric carcinoma.

|

|

Abdominal Distention

Associated Clinical Features

Abdominal distention may be a

symptom—often described by the patient as the feeling of being

bloated—or a sign, an obvious protuberance of the patient's abdomen

that may or may not be out of proportion to the rest of the body. Other

findings vary widely, depending on the cause. In obesity, the abdomen is

uniformly rounded while an increase in girth and fat concurrently

accumulates in other parts of the body. In patients with ascites, there

may be shifting dullness, a fluid wave, bulging flanks, or hepatomegaly.

In patients with neoplasms, there may be a palpable mass. In gravid

patients, fetal heart tones may be present and fetal motion may be felt.

In patients with excess gas from bowel obstruction, there may be absent

or high-pitched bowel sounds and absence of bowel movements or flatus.

Differential Diagnosis

Numerous conditions present with

abdominal distention. Obesity, ascites, pregnancy, neoplasms, aneurysm,

tympanites (excess gas), organomegaly, and feces are important etiologies

to consider in the differential.

The profile of the fluid-filled

abdomen of ascites (Fig. 7.29) is a single curve from the xiphoid process

to the pubic symphysis. The umbilicus may be everted, and there may be

prominent superficial abdominal veins. Other physical findings suggestive

of ascites include shifting dullness and a fluid wave.

|

|

|

|

|

Ascites Ascites in an alcoholic man. Note the everted

umbilicus and prominent superficial abdominal veins. (Courtesy of

Alan B. Storrow, MD.)

|

|

The pregnant abdomen profile (Fig. 7.30) shows the

outward curve to be more prominent in the lower half of the abdomen. The

umbilicus may be everted in the last trimester of pregnancy. Prominent

abdominal wall veins may also be seen. The presence of fetal heart tones

confirms the diagnosis.

|

|

|

|

|

Gravid

Abdomen The abdomen of a woman

at 39 weeks' gestation. Note the abdominal wall striae, everted

umbilicus, and prominent superficial abdominal wall veins. (Courtesy

of Stephen Corbett, MD.)

|

|

The abdominal profile of a patient with a leaking

abdominal aortic aneurysm (Fig. 7.31) shows a mottled abdominal wall

reflective of hypoperfusion of this structure. There may be a curve of

the midabdomen to either side of the aorta, more often on the left.

Palpation of a pulsatile mass supports the diagnosis. Ultrasound or

computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen will confirm the diagnosis.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

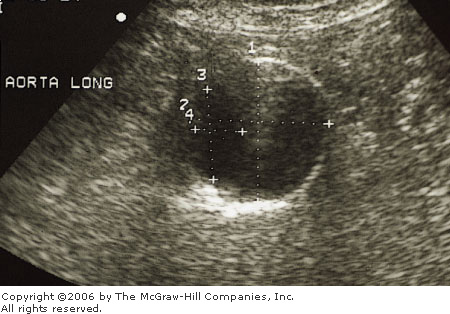

Abdominal

Aortic Aneurysm A. The abdomen

of a patient with a leaking abdominal aortic aneurysm. Note the mottled

abdominal wall and the prominent curvature of the right side of the

abdomen. (Courtesy of Stephen Corbett, MD.) B. Abdominal aortic

aneurysm seen on ultrasound in another patient. (Courtesy of Sally

Santen, MD.)

|

|

Excess abdominal air (Fig. 7.32) can be located in

the lumen of the stomach or intestines or free in the peritoneum. This

abdominal profile is a single curve from the xiphoid process to the pubic

symphysis. Nausea, vomiting, decreased bowel sounds, and colicky pain are

present in a small bowel obstruction. Large bowel obstruction may be

accompanied by feculent vomiting and absent production of flatus.

|

|

|

|

|

Pseudoobstruction An 85-year-old woman was brought from a

nursing home with a complaint of abdominal distention and pain for 1

to 2 days. An eventual diagnosis of Ogilvie's syndrome, or

pseudoobstruction of the large bowel, was made. This is usually seen

in debilitated patients and can be treated with decompression.

(Courtesy of Stephen Corbett, MD.)

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment varies widely depending

on the cause; thus emergent management is directed at determining the etiology.

Life-threatening causes (aneurysm, obstruction, neoplasms) require

stabilization and referral for definitive treatment.

Clinical Pearl

1. The "six f's" can

categorize conditions causing abdominal distention: fat, flatus, fetus,

fluid, feces, fatal growth.

|

|

Intertrigo

Associated Clinical Features

Intertrigo is a dermatitis

occurring on apposed surfaces of skin, such as the creases of the neck,

folds of the groin and armpit, or a panniculus (Fig. 7.33). It is

characterized by a tender, red plaque with a moist, macerated surface. A

candidal infection may result and often becomes secondarily infected with

skin flora. Erythema, fissures, burning, itching, exudates, and fever may

also accompany intertrigo.

|

|

|

|

|

Intertrigo

of the Panniculus Note the

exudate, erythema, and fissures of the abdominal wall. This patient

also had fever, suggesting secondary infection. (Courtesy of Lawrence

B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Necrotizing fasciitis of the

abdominal wall, cellulitis, and Candida albicans infection should

be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Local care, empiric topical

antifungal treatment, and good personal hygiene are recommended.

Intravenous antibiotics initiated in the ED directed against skin flora

are recommended if there is secondary infection.

Clinical Pearl

1. Consider necrotizing

fasciitis of the abdominal wall if the patient appears septic.

|

|

Abdominal Wall Hematoma

Associated Clinical Features

Mild trauma may produce hematomas

of the rectus sheath (Fig. 7.34). This injury results in intense

abdominal pain, which can mimic an acute abdomen. The diagnosis is made

by physical examination, since the ecchymosis is not always visible.

Palpation of the abdominal wall reveals a tender mass that is accentuated

by contraction of the rectus. Ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) may

confirm the diagnosis.

|

|

|

|

|

Abdominal

Wall Hematoma This 50-year-old

man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease developed

right-lower-quadrant pain after an episode of coughing. A repeat

examination on the second visit showed clearly visible ecchymosis.

There was no coagulopathy and amylase was normal. A CT scan revealed

a 10- by 8-cm hematoma in the right rectus abdominis sheath.

(Courtesy of Stephen Corbett, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Multiple causes of abdominal pain

must be considered in the differential diagnosis. Careful examination

with supplemental imaging studies, if needed, helps with the diagnosis.

Two classic signs of retroperitoneal bleeding are Grey-Turner's sign

(flank ecchymosis) and Cullen's sign (periumbilical ecchymosis).

Hemorrhagic pancreatitis and ruptured ectopic pregnancy, respectively,

should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Assuming that there is no underlying

blood dyscrasia or coagulopathy, hematomas of the rectus sheath usually

resolve in 1 to 2 weeks.

Clinical Pearl

1. Fothergill's sign is

enhancement of a rectus sheath hematoma when the abdominal wall is

tensed. The mass should not cross the midline and should be easier to

palpate with abdominal muscle contractions. Intraabdominal masses are

more difficult to palpate with such contractions.

|

|

Abdominal Striae (Striae Atrophicae)

Associated Clinical Features

Abdominal striae are linear,

depressed, pink or bluish scar-like lesions (Fig. 7.35) that may later

become silver or white. They are caused by weakening of the elastic

cutaneous tissues from chronic stretching. They most commonly occur on

the abdomen but are also seen on the buttocks, breasts, and thighs.

Striae are commonly seen in obesity, pregnancy, Cushing's syndrome, and

chronic topical corticosteroid treatment. In Cushing's syndrome, a state

of adrenal hypercorticism, the skin becomes fragile and easily breaks

from normal stretching.

|

|

|

|

|

Abdominal

Striae These striae are seen

in a patient with recent weight gain, moon facies, and altered mental

status. The patient was diagnosed with Cushing's syndrome. (Courtesy

of Geisinger Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine,

Danville, PA.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Obesity, pregnancy, Cushing's

syndrome, and chronic topical corticosteroid treatment should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

This finding seldom presents as a

condition requiring acute treatment; thus, attention is directed to

determining and treating the underlying cause.

Clinical Pearls

1. Recent striae (pink or blue)

with moon facies, hypertension, renal calculi, osteoporosis, and

psychiatric disorders are suggestive of Cushing's syndrome.

2. The striae caused by

pregnancy typically fade with time, unlike those associated with

Cushing's syndrome.

|

|