|

Note: Large images and

tables on this page may necessitate printing in landscape mode.

Copyright

©2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved.

Emergency

Medicine Atlas > Part 1. Regional

Anatomy > Chapter 8. Urologic Conditions >

|

Testicular Torsion

Associated Clinical Features

These patients are most often

young men (average age 16 to 17.5 years) who present complaining of the

sudden onset of pain in one testicle. The pain is then followed by

swelling of the affected testicle, reddening of the overlying scrotal

skin, lower abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. An examination reveals

a swollen, tender, retracted testicle (Fig. 8.1) that often lies in the

horizontal plane (bell-clapper deformity) (Figs. 8.2 and 8.3). The

spermatic cord is frequently swollen on the affected side. In delayed

presentations, the entire hemiscrotum may be swollen, tender, and firm

(Fig. 8.4). The urine is usually clear with a normal urinalysis. In

one-third of cases there is a peripheral leukocytosis.

|

|

|

|

|

Testicular

Torsion Swollen, tender

hemiscrotum, with erythema of scrotal skin and retracted testicle.

(Courtesy of Stephen Corbett, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bell-Clapper

Deformity A bell-clapper

deformity in testicular torsion results from the twisting of the

spermatic cord and causes the testis to be elevated, with a

horizontal lie. The lack of fixation of the tunica vaginalis to the

posterior scrotum predisposes the freely movable testis to rotation

and subsequent torsion. An elevated testis with a horizontal lie may

be seen in asymptomatic patients at risk for torsion.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Testicular

Torsion A retracted testicle

consistent with early testicular torsion is seen. (Courtesy of David

W. Munter, MD, MBA.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Testicular

Torsion Swollen, tender

scrotal mass. (Courtesy of Patrick McKenna, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Alternative diagnoses that should

be considered include acute epididymitis, torsion of the testicular

appendix (Fig. 8.5), trauma, acute orchitis (mumps), hydrocele,

spermatocele, varicocele, hernia, and tumor. A good history and physical

examination helps narrow the diagnosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Urologic consultation should be

obtained immediately and preparations made to go to the operating room

without delay. Doppler ultrasound or technetium scanning may be helpful

if these procedures will not delay surgery. In the interim, detorsion may

be attempted if the patient is seen within a few hours of onset: the

affected testicle should initially be opened like a book, that is, the

right testicle turned counterclockwise when viewed from below and the

left testicle turned clockwise when viewed from below. Pain relief should

be immediate. Decreased pain should prompt additional turns (as many as

three) to complete detorsion; increased pain should prompt detorsion in

the opposite direction. Ancillary studies should not delay operative intervention,

since testicular infarction will occur within 6 to 12 h after torsion.

Clinical Pearls

1. The cremasteric reflex is

almost always absent in testicular torsion.

2. Patients may report similar,

less severe episodes that spontaneously resolved in the recent past.

3. Half of all torsions occur

during sleep.

4. Abdominal or inguinal pain

is sometimes present without pain to the scrotum.

5. The age of presentation has

a bimodal pattern, since torsion is also more prevalent during infancy

and adolescence.

|

|

Torsion of a Testicular or Epididymal Appendix

Associated Clinical Features

Small vestigial remnants in the

embryology of the scrotum are often found on the superior portions of the

testicle or the epididymis. These appendages, which have no known

function, are occasionally on a stalk that is subject to torsion. This

most commonly occurs in boys up to 16 years of age but has been reported

in adults. The patient will complain of sudden pain around the superior

pole of the testicle or epididymis as the appendix undergoes necrosis and

inflammation. Early in the course, palpation of a firm, tender nodule in

this area will confirm the diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Later in the course of

appendiceal torsion, swelling and pain generalize to the rest of the

scrotum. At this point the condition may be difficult to differentiate

from testicular torsion, acute epididymitis, or acute orchitis.

Hydrocele, spermatocele, varicocele, hernia, and tumor must also be

considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Urologic consultation should be

obtained immediately. Differentiating from the more emergent testicular

torsion is the key responsibility. Ancillary studies are generally not

helpful in making this diagnosis unless it presents very early in its

course. A urinalysis is generally normal. The characteristic physical

signs of a small, tender, upper-pole nodule along with a color Doppler

ultrasound showing good flow to the testicle may mitigate the need for

emergent surgery. With later presentations or an equivocal ultrasound,

the diagnosis may not be made with confidence before surgery. Necrotic

appendices are excised if found during an exploration to rule out

testicular torsion. If surgery is not deemed necessary by the urologic

consultant, analgesics and rest are all that is required. The appendix

will involute and calcify in 1 to 2 weeks.

Clinical Pearls

1. Stretching of the scrotal

skin across the necrotic nodule will occasionally reveal a bluish

discoloration of the nodule, called the "blue-dot sign" (Fig.

8.5). This is pathognomonic for torsion of the appendix.

2. A reactive hydrocele may

accompany appendiceal torsion. When the hydrocele is transilluminated,

the blue-dot sign may be revealed.

|

|

|

|

|

Blue-Dot

Sign A blue-dot sign is caused

by torsion of the testicular appendix. It is best seen with the skin

held taut over the testicular appendix. (Courtesy of Javier A.

Gonzalez del Rey, MD.)

|

|

|

|

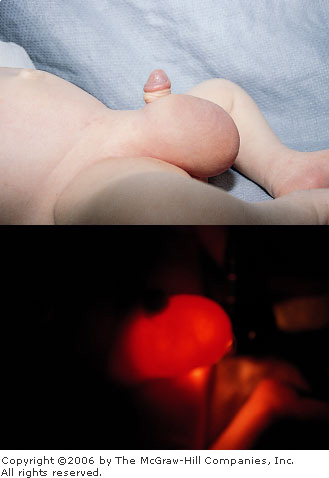

Hydrocele

Associated Clinical Features

Most hydroceles occur in older

patients and develop gradually without any significant symptoms. A

hydrocele generally presents as a soft, pear-shaped, fluid-filled cystic

mass anterior to the testicle and epididymis that will transilluminate

(Fig. 8.6). However, it can be tense and firm and will transilluminate

poorly if the tunica vaginalis is thickened. Almost all hydroceles in

children are communicating, resulting from the same mechanism that causes

inguinal hernia. A persistent narrow processus vaginalis acts like a

one-way valve, thus permitting the accumulation of dependent peritoneal

fluid in the scrotum. Acute symptomatic hydroceles are more rare and can

occur in association with epididymitis, trauma, or tumor.

|

|

|

|

|

Hydrocele Painless swelling in the scrotum of a young

boy (top). Transillumination of the swelling (bottom)

identifies the hydrocele. (Courtesy of Michael J. Nowicki, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Painless masses that must be

differentiated from hydrocele include spermatocele, varicocele, inguinal

hernia, and tumor. Painful masses to be differentiated include traumatic

hematocele, epididymitis, orchitis, and torsion.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

In an acute hydrocele, treatment

must be directed at discovering a possible underlying cause. A positive

urinalysis may point toward an infectious etiology. Transillumination

helps demonstrate whether the mass is cystic or solid. Ultrasound can be

very helpful in imaging the scrotal contents and delineating the

composition of the mass. Acute hydroceles should not be considered benign

and require referral to a urologist to rule out tumor or infection.

Chronic accumulations are referred to a urologist on a more routine basis

for elective drainage.

Clinical Pearls

1. Ten percent of testicular

tumors have a reactive hydrocele as the presenting complaint.

2. An inguinal hernia with a

loop of bowel in it may emit bowel sounds.

3. Hydroceles are almost never

symptomatic.

4. Acute reactive hydroceles

may be caused by infection, trauma, or torsion.

|

|

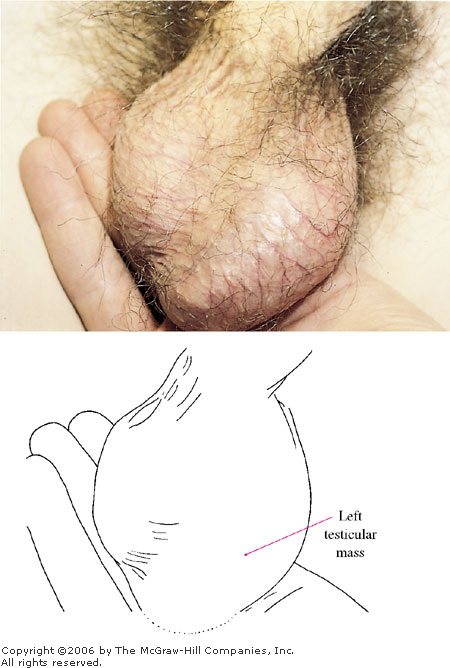

Testicular Tumor

Associated Clinical Features

In testicular tumor, a painless,

firm testicular mass (Fig. 8.7) is palpated, with the patient often

complaining of a "heaviness" of his testicle. If the patient

presents early, the mass will be distinct from the testis, whereas later

presentations will have generalized testicular or scrotal swelling. These

lesions occasionally present with pain due to infarction of the tumor.

|

|

|

|

|

Testicular

Tumor This painless left

testicular mass is highly suspicious for tumor, as proved to be the

case in this patient. (Courtesy of Patrick McKenna, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Epididymitis is the most frequent

misdiagnosis, which unfortunately may delay surgical intervention. When

the tumor presents with infarction pain, differentiation from

epididymitis or torsion can be difficult. In some cases, ultrasound can

help differentiate these entities.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Patients should be promptly

referred to a urologist for surgical exploration.

Clinical Pearls

1. Acute hydroceles and

hematoceles should prompt the physician to consider a tumor as the cause.

2. Pain from tumor infarction

is usually not as severe as pain due to torsion or epididymitis.

3. Findings of an unexplained

supraclavicular lymph node, abdominal mass, or chronic nonproductive

cough resistant to conventional therapy should prompt a testicular

examination for tumor.

|

|

Scrotal Abscess

Associated Clinical Features

A scrotal abscess is a

suppurative mass with surrounding erythema involving the superficial

layers of the scrotal wall (Fig. 8.8). The usual history is of

progressive swelling of a small pustule or papule followed by increasing

pain and induration or fluctuance. Constitutional symptoms and fever are

generally absent.

|

|

|

|

|

Scrotal

Abscess Suppurative mass on

the scrotum. (Courtesy of David Effron, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

An apparently superficial scrotal

abscess must be distinguished from a deep scrotal abscess or early

Fournier's gangrene. In the latter two cases, patients tend to appear

quite ill. The erythema of the skin overlying an abscess should not be

mistaken for an urticarial reaction, erythema multiforme, or drug

eruption.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Using local anesthesia, simply

make a stab incision and drain the abscess. The patient is then

instructed to use a sitz bath and to change the dressing frequently. An

alternative method of treatment is to unroof the abscess by

circumferential excision. This ensures that there is adequate wound drainage.

Immunocompromised patients may require intravenous antibiotics and

admission.

Clinical Pearl

1. If the patient appears ill

out of proportion to the superficial appearance, suspect that this mass

is the point of a deep scrotal abscess.

|

|

Fournier's Gangrene

Associated Clinical Features

Fournier's gangrene most

frequently occurs in a middle-aged diabetic male who presents with

swelling, erythema, and severe pain of the entire scrotum (Fig. 8.9), but

it is also known to occur in females (Fig. 8.10). In males, the scrotal

contents often cannot be palpated because of the marked inflammation. The

patient has constitutional symptoms with fever and frequently is in

shock. There is often a history of recent urethral instrumentation, an

indwelling Foley catheter, or perirectal disease. A localized area of

fluctuance cannot be appreciated.

|

|

|

|

|

Fournier's

Gangrene Markedly swollen,

necrotic, tender scrotum, perineum, and adjacent thighs are seen.

(Courtesy of David Effron, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fournier's

Gangrene Swollen, tender,

erythematous labia, perineum, and inner thighs in a female patient

with Fournier's gangrene. (Courtesy of Daniel L. Savitt, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis

includes cellulitis, superficial scrotal abscess, edema due to heart

failure or lymphatic obstruction, allergic reaction, and

epididymoorchitis with skin fixation.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

These patients require aggressive

fluid resuscitation and early surgical consultation for immediate

debridement and surgical drainage. Broad-spectrum antibiotics effective

against gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms should be

given as soon as possible in the ED. There is anecdotal experience that

treatment is enhanced by hyperbaric oxygen.

Clinical Pearls

1. Pain out of proportion to

the clinical findings may represent an early presentation of Fournier's

gangrene.

2. A plain pelvic radiograph

may reveal subcutaneous air.

3. Fournier's gangrene is

usually quite painful but has been known to present with only a mildly

uncomfortable necrosis of the scrotal wall and exposed testis.

|

|

Paraphimosis

Associated Clinical Features

Paraphimosis is the entrapment of

a retracted foreskin that cannot be reduced behind the coronal sulcus (Fig.

8.11). Pain, swelling, and erythema are common. If severe, the

constriction causes edema and venous engorgement of the glans, which can

lead to arterial compromise with subsequent tissue necrosis.

|

|

|

|

|

Paraphimosis Moderate edema of retracted foreskin, which is

entrapped behind the coronal sulcus. (Courtesy of Alan C. Heffner,

MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

In contrast to paraphimosis,

phimosis is the inability to retract the foreskin (Fig. 8.12), usually a

chronic condition. Other diagnoses to consider include superficial

balanitis, hair tourniquet, contact dermatitis, and urticaria.

|

|

|

|

|

Phimosis In phimosis, the foreskin cannot be retracted,

often due to meatal stenosis and scarring.

|

|

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Squeezing the glans firmly for 5

min to reduce the swelling can lead to successful reduction of the

foreskin. Local infiltration of anesthesia with vertical incision of the

constricting band should be performed by a urologist if manual reduction fails.

Clinical Pearls

1. In the presence of arterial

compromise, if a urologist is not immediately available, the emergency

physician should incise the constricting band.

2. The patient should be

referred to a urologist for circumcision if successfully reduced.

3. Phimosis is

"physiologic" in young males (generally less than 5 to 6 years

old).

4. Phimosis, if

"reduced" (retracted proximally over the glans), can cause a

paraphimosis—a true emergency.

|

|

Priapism

Associated Clinical Features

These patients present with

persistent, usually painful erection due to pathologic engorgement of the

corpora cavernosa (Fig. 8.13). Patients may present within several hours

or several days of their first symptoms. The glans penis and corpus

spongiosum are generally not engorged and remain flaccid. The physiology

is either arterial, which is generally traumatic, or venoocclusive.

Reversible causes of venoocclusive disease include sickle cell disease,

direct injection of erectile agents, and leukemic infiltration. Nonreversible

causes include idiopathic ones—the most common, spinal cord

lesions, and a variety of medications.

|

|

|

|

|

Priapism A painful persistent erection due to

pathologic engorgement of the corpora cavernosa is seen in this

patient with sickle cell disease. The glans penis and corpus

spongiosum are not engorged (Courtesy of Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Priapism is confirmed when there

is a prolonged erection with a flaccid glans and corpus spongiosum. The

history and physical examination should be directed toward signs of

trauma, infection, medications, drug use, and the diseases that

predispose to priapism. Traumatic priapism is more flaccid and generally

less painful than the venoocclusive form.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The diseases that are associated

with reversible priapism should be treated. Ice packs to the perineum

have traditionally been recommended but are frequently unsuccessful.

Terbutaline given orally or subcutaneously occasionally reverses

priapism. Aspiration of blood from the corpus cavernosum can lead to

detumescence and should be followed by a compressive dressing. Injectable

erectile agents can be reversed by aspiration followed by intracavernous

injection of alpha-adrenergic agents such as phenylephrine. Urologic

consultation should be obtained immediately for traumatic or persistent

priapism despite initial treatment, with close urologic follow-up for

those that are successfully reversed in the ED. Patients with persistent

priapism despite treatment must frequently undergo surgery.

Clinical Pearls

1. Patients should be advised

that impotence is a frequent complication of priapism, regardless of the

length of the symptoms or the success of any treatment.

2. Although the glans penis and

corpus spongiosum are generally not affected, urinary retention often

accompanies priapism.

|

|

Urethral Rupture

Associated Clinical Features

Urethral injury is rarely an

isolated event; it is often associated with multiple trauma. Anterior

urethral injuries are most often the result of a straddle injury and may

present late (many patients are still able to void), with a local infection

or sepsis from extravasated urine. Posterior urethral injuries occur in

motor vehicle and motorcycle accidents and are usually the result of

pelvic fractures. Patients have blood at the urethral meatus (Fig. 8.14),

cannot void, and have perineal bruising. In males, the prostate is often

boggy or free-floating or may not be palpable at all if there is a

retroperitoneal hematoma between the prostate and the rectum.

|

|

|

|

|

Urethral

Rupture Blood at the urethral

meatus in a patient with urethral rupture secondary to trauma.

(Courtesy of David Effron, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Bladder rupture, higher urinary

tract injuries, urethritis, and penile fracture may all present with

blood at the meatus.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Urethral instrumentation such as

Foley catheterization should not occur prior to a retrograde urethrogram

with highly concentrated water-soluble contrast. If there is only a

partial anterior tear, a gentle attempt at catheterization can be made if

it is abandoned at the first sign of resistance. If catheterization is

unsuccessful and whenever there is a posterior tear, a suprapubic

catheter should be placed in the ED with a trocar if relief of bladder

distention is required prior to operative repair.

Clinical Pearls

1. Foley catheter insertion is

contraindicated in patients with a suspected urethral injury prior to a

retrograde urethrogram.

2. Urethral injury should be

suspected in the multiple trauma patient who is unable to void or has

blood at the meatus, a high-riding prostate, or perineal trauma.

3. Vaginal lacerations due to

trauma in females should prompt consideration of a urethral tear.

4. Occasionally urine from an

anterior urethral tear will extravasate into the scrotum, causing marked

swelling.

5. Posterior injuries are

frequently associated with other intraabdominal injury.

|

|

Fracture of the Penis

Associated Clinical Features

Patients usually present

complaining of trauma during sexual arousal and often relate experiencing

a sudden "snapping" sound or sensation, pain, and deformity,

which is caused by a tearing of the tunica albuginea. The shaft of the

penis is swollen and often angulated at the fracture site (Fig. 8.15).

|

|

|

|

|

Fractured

Penis A swollen, ecchymotic

penis is shown. Note the angulation at the midshaft of the penis,

indicating the "fracture" site. Blood at the meatus, as

shown here, is further evidence of a urethral injury. (Courtesy of

Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Penile fracture can be confused with

penile trauma without tear of the tunica albuginea, urethral injury,

Peyronie's disease (dorsal contracture), priapism, or foreign bodies.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

If the patient cannot urinate, a

retrograde urethrogram may be required to rule out urethral injury (Fig.

8.16). These patients require admission and referral to a urologist, who

frequently takes them immediately to the operating room for repair.

|

|

|

|

|

Fractured

Penis Retrograde urethrogram

showing urethral injury from the fractured penis in Fig. 8.15.

(Courtesy of David W. Munter, MD.)

|

|

Clinical Pearls

1. Patients sometimes concoct

elaborate, non-sexually-related stories surrounding the circumstances of

injury, but penile fracture most commonly occurs during sexual arousal.

2. Penile implants are also

subject to injury in a similar fashion.

|

|

Straddle Injury

Associated Clinical Features

In straddle injury, the patient

has pain, swelling, contusion, and hematoma of the perineum or scrotum

following direct blunt trauma (Figs. 8.17 and 8.18). This injury is

commonly caused by a fall onto a bicycle frame cross-tube, playground

equipment, or a toilet seat. Swelling can be severe enough to interfere

with urination. Scrotal contents can also be contused or crushed with

this injury.

|

|

|

|

|

Straddle

Injury Ecchymosis, swelling,

and contusion of the perineum in a 3-year-old female who tripped and

fell on a large plastic toy. (Courtesy of James Mensching, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Straddle

Injury Contusion of the

scrotum and lower abdomen in a young boy consistent with a straddle

injury. (Courtesy of David W. Munter, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Fournier's gangrene, cellulitis,

and urticaria are similar in appearance but without the history of

trauma. Sexual or physical abuse should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment is supportive and

includes cold packs, elevation, rest, and analgesics. If unable to void,

the patient may require catheterization.

Clinical Pearls

1. Laceration of the perineum

can be obscured by swelling if a careful examination is not performed.

2. Pelvic radiographs should be

obtained in all perineal injuries.

3. Males and females are at

high risk for urethral injuries with this type of injury.

4. Straddle injury is

differentiated from abuse with a good history from a reliable caregiver

that matches the injury.

|

|

Balanoposthitis

Associated Clinical Features

Balanoposthitis is an infection

and inflammation of the glans penis that also involves the overlying

foreskin (prepuce) (Fig. 8.19). Balanitis is isolated to the

glans, whereas posthitis involves only the prepuce. Pain, erythema,

and edema of the affected parts of the penis are typically present.

Patients may refrain from urination secondary to dysuria, or the edema

may induce meatal occlusion, leading to urinary retention or obstruction.

Common etiologies include overgrowth of normal bacterial flora secondary

to poor hygiene (pediatric patients), sexually transmitted diseases

(adolescents and adults), and candidal infections (the elderly or

immunocompromised) (Fig. 8.20).

|

|

|

|

|

Balanoposthitis Note the erythema, localized edema, and

significantly constricted preputial orifice of the distal penis.

(Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Balanitis Candidal balanitis in an elderly patient with

no other complaints. New-onset diabetes was diagnosed. (Courtesy of

Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually

straightforward; however, the underlying etiology often must also be

addressed. Examples are sexually transmitted diseases in healthy adults

and diseases associated with immunocompromise (e.g. diabetes mellitus,

AIDS, alcoholism). Phimosis occurs when chronic infection due to poor

hygiene causes fibrosis and contracture of the preputial opening. Other

diagnoses to consider include contact dermatitis, fixed drug eruptions,

lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, and squamous cell carcinoma.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment is directed at the

suspected etiology. Warm soaks and topical antibiotics (bacitracin) are

the mainstay of therapy for infectious etiologies owing to poor hygiene.

Parents should be counseled about proper cleansing and handling of the

prepuce. Oral or intravenous antibiotics may be indicated if there is an

accompanying cellulitis. If urinary obstruction is present,

catheterization may be attempted using a small catheter. If

catheterization is unsuccessful, urologic consultation for emergent

surgical correction of the prepuce is required. Candidal infections are

treated with meticulous hygiene and topical antifungal agents. Routine

urologic referral is indicated for suspected lichen sclerosus et

atrophicus and squamous cell carcinoma.

Clinical Pearls

1. The inability to retract the

foreskin completely is normal in young males up to age 4 or 5. Attempting

to do so could cause a paraphimosis, a true emergency.

2. Placing the child in a

bathtub with warm water will help alleviate difficulty with micturition

assuming that no obstruction is present.

3. Candidal balanitis or

balanoposthitis may be associated with an undiagnosed immunocompromised

state.

4. Suspected sexually

transmitted diseases require treatment for the partners as well.

|

|