|

Note: Large images and

tables on this page may necessitate printing in landscape mode.

Copyright

©2006 The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved.

Emergency

Medicine Atlas > Part 1. Regional

Anatomy > Chapter 9. Sexually Transmitted Diseases and

Anorectal Conditions > Sexually Transmitted Diseases >

|

Primary Syphilis

Associated Clinical Features

Lesions of primary syphilis

generally appear after an incubation period of 2 to 6 weeks, but they may

appear up to 3 months after exposure. The patient usually presents with a

solitary round to oval painless genital ulcer (Figs. 9.1 and 9.2).

However, the ulcer may be slightly painful, and several lesions are

sometimes seen. The base of the genital ulcer is dry in males, moist in

females; purulent fluid in the base is uncommon. The borders of the ulcer

are often indurated. Patients may develop ulcers at any site of

inoculation on the body. Bilateral, nontender, nonfluctuant adenopathy is

common. Lesions resolve spontaneously in 3 to 12 weeks without treatment

as the infection progresses to the secondary stage. Patients with primary

syphilis are at risk for concurrent infection with other sexually transmitted

diseases.

|

|

|

|

|

Primary

Chancre—Male This

dry-based, painless ulcer with indurated borders is typical for a primary

chancre in a male patient. (Courtesy of A. Wisdom: Sexually

Transmitted Diseases. London: Mosby-Wolfe; 1992.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Primary

Chancre—Female A

solitary, painless genital chancre with a clean base in a patient

with primary syphilis. (Courtesy of the Department of Dermatology,

Naval Medical Center, Portsmouth, VA.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Behçet's disease, fixed drug

eruption, recurrent genital herpes, chancroid, squamous cell carcinoma,

and lesions caused by trauma can have a similar appearance.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treat with benzathine penicillin

G, 2.4 million units IM once. Penicillin-allergic patients should be

given doxycycline, 100 mg PO bid for 2 weeks. Other alternatives include

tetracycline, 500 mg PO qid for 2 weeks; erythromycin base, 500 mg PO qid

for 2 weeks; or ceftriaxone, 250 mg IM once daily for 10 days. An RPR or

VDRL should be checked. Partners within the last 90 days should be

treated presumptively; partners over the last 90 days should be treated

on the basis of their serologic testing results. This is a reportable

disease, and appropriate paperwork should be filed.

Clinical Pearls

1. Lesions are usually painless

and solitary, but they may be slightly painful; two or three lesions may

also be seen.

2. Consider dark-field

examination of the lesion to rapidly confirm the diagnosis.

3. Chancres of primary syphilis

can occur anywhere on the body at the site of inoculation.

4. Evaluate patients with

primary syphilis for concurrent sexually transmitted diseases and treat

accordingly.

|

|

Secondary Syphilis

Associated Clinical Features

The rash of secondary syphilis

often occurs 2 to 10 weeks after resolution of the primary lesions. It

begins as a nonpruritic macular rash that evolves into a papulosquamous

rash involving primarily the trunk, palms, and soles (Figs. 9.3, 9.4,

9.5). The rash is often annular in shape. Diffuse, painless

lymphadenopathy is also seen at this stage. Mucous patches represent

mucous membrane involvement of the tongue and buccal mucosa (Fig. 9.6).

Condyloma lata (Fig. 9.7) can be seen during this stage, as can patchy

alopecia. The manifestations of this stage resolve without treatment in

several months.

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary

Syphilis—Trunk Rash on

trunk in secondary syphilis. (Courtesy of A. Wisdom: Sexually

Transmitted Diseases. London: Mosby-Wolfe; 1992.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary

Syphilis—Palms

Papulosquamous rash of secondary syphilis. Note the annular

appearance of the palmar rash. (Courtesy of H. Hunter Handsfield: Atlas

of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1992.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary

Syphilis—Soles

Hyperkeratotic plantar rash in a patient with secondary syphilis.

(Courtesy of H. Hunter Handsfield: Atlas of Sexually Transmitted

Diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1992.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

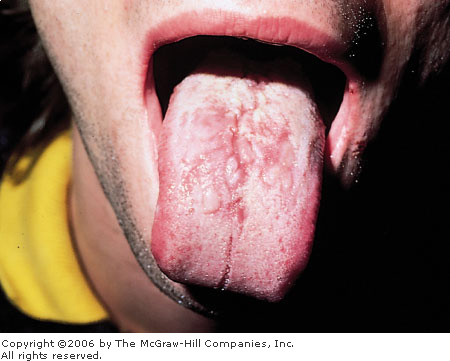

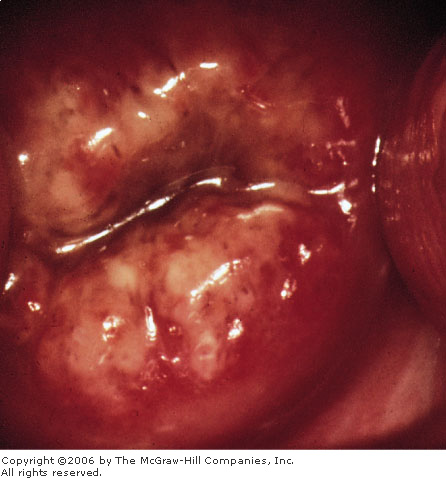

Mucous

Patches Oral involvement in

secondary syphilis manifest by mucous patches. These lesions are very

infectious, and dark-field examination is often positive for

spirochetes. (Courtesy of Morse, Moreland, Thompson: Atlas of

Sexually Transmitted Diseases. London: Mosby-Wolfe; 1990.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

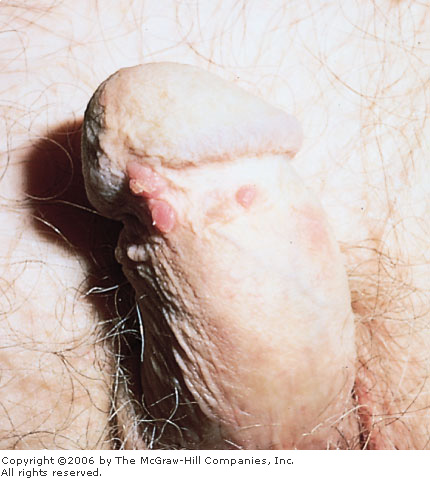

Condyloma

Lata Typical appearance of the

verrucous, heaped up lesions of condyloma lata, a manifestation of

secondary syphilis. (Courtesy of H. Hunter Handsfield: Atlas of

Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1992.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis

depends on the site involved:

Rash: Pityriasis

rosea, psoriasis, lichen planus, Reiter's syndrome, viral syndrome, allergic

rash

Mucous patches: Apthous

ulcerations, thrush

Condyloma lata: Condyloma

accuminata, squamous cell carcinoma, granuloma inguinale

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Benzathine penicillin G, 2.4

million units IM once; penicillin allergic patients should receive

doxycycline, 100 mg PO bid for 2 weeks. RPR or VDRL should be sent and

titers followed to determine adequate response to therapy. Suspected and

confirmed cases of syphilis must be reported to public health officials.

Clinical Pearls

1. Lesions of secondary

syphilis are very infectious. It is prudent to always wear gloves when

examining a patient with a rash that may be due to secondary syphilis.

2. Consider using dark-field

examination of scrapings of the rash, mucous patches, and condyloma lata

to make a rapid diagnosis.

3. Patients should be warned

about the potential development of the Jarish-Herxheimer reaction after

they are treated. This syndrome, characterized by fever, headache,

malaise, and myalgias, occurs within 24 h of treatment and is caused by

massive release of pyrogens by the dying spirochetes.

|

|

Gonorrhea

Associated Clinical Features

Gonorrhea often becomes manifest

after a short incubation period of 2 to 5 days. In men, urethritis is

characterized by purulent, usually copious urethral discharge (Fig. 9.8)

with dysuria; however, up to 10% of men are asymptomatic. Women may also

develop urethritis (Fig. 9.9) and complain of dysuria. Cervicitis is

often asymptomatic. If symptomatic, women may complain of increased vaginal

discharge or vaginal spotting, particularly after intercourse. On

speculum examination, the cervix is friable, with a mucopurulent

endocervical exudate (Fig. 9.10). Patients with gonococcal conjunctivitis

have chemosis and copious purulent exudate (Fig. 9.11); untreated, these

patients can develop endophthalmitis and perforation of the globe.

Untreated gonorrhea may disseminate and more commonly does so in women.

Disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI) typically presents with a

monoarticular septic arthritis usually involving the knees, ankles,

elbows, or wrists. Skin lesions are necrotic pustules on an erythematous

base; they may ulcerate and are more commonly found on the distal

extremities (Figs. 9.12, 9.13).

|

|

|

|

|

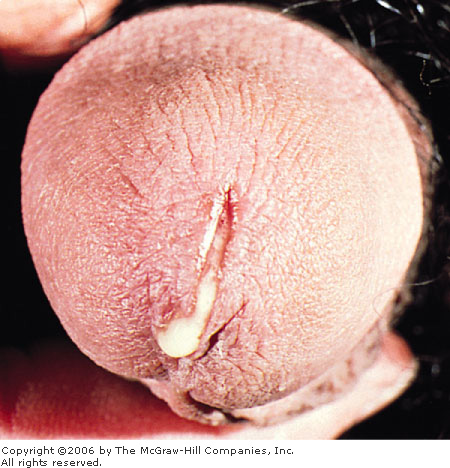

Male

Urethritis Purulent, copious

urethral discharge in a patient with gonococcal urethritis. (Courtesy

of H. Hunter Handsfield: Atlas of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New

York: McGraw-Hill; 1992.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Female

Urethritis Gonococcal

urethritis in a female patient. Note the purulent urethral discharge.

(Courtesy of Morse, Moreland, Thompson: Atlas of Sexually

Transmitted Diseases. London: Mosby-Wolfe; 1990.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

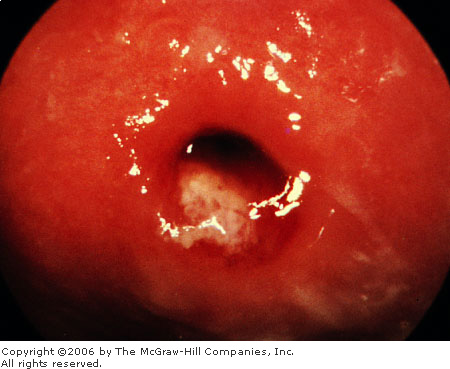

Cervicitis Endocervical purulent exudate in an

asymptomatic patient with gonococcal cervicitis. The cervix is very

friable. (Courtesy of King K. Holmes, MD, from H. Hunter Handsfield: Atlas

of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1992.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conjunctivitis Chemotic conjunctiva and copious purulent

exudate in a patient with gonococcal conjunctivitis. (Courtesy of H.

Hunter Handsfield: Atlas of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New

York: McGraw-Hill; 1992.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Skin

Lesions Small pustules with

hemorrhage suggestive of the skin lesions of disseminated gonococcal

infection. (Courtesy of H. Hunter Handsfield: Atlas of Sexually

Transmitted Diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1992.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bartholin's

Cyst Enlarged, fluctuant,

tender Bartholin's abscess of the labia, usually but not always a

result of gonorrhea. (Courtesy of A. Wisdom: Sexually Transmitted

Diseases. London: Mosby-Wolfe; 1992.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis

depends on the site involved:

Urethritis and cervicitis:

Chlamydia, Mycoplasma, Ureaplasma

Conjunctivitis: Bacterial

conjunctivitis, chemical conjunctivitis

Arthritis: Septic

arthritis, rheumatic fever, hepatitis B prodrome, immune complex disease,

Reiter's syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus

Skin lesions:

Folliculitis, subacute bacterial endocarditis (septic emboli)

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Treatment is dependent on the

site of infection:

Urethritis and cervicitis: Ceftriaxone,

125 mg IM once; cefixime, 400 mg PO once; ciprofloxacin, 500 mg PO once;

ofloxacin, 400 mg PO once.

Conjunctivitis: Ceftriaxone

1 g IM once; eye irrigation.

Disseminated gonococcal

infection: Ceftriaxone, 1 g IV or IM daily for 7 to 10 days; may

treat with 1 to 2 days of IM ceftriaxone and then change to cefixime, 400

mg PO bid, or ciprofloxacin, 500 mg PO bid, to complete a 7- to 10-day

course. Sexual partners should be notified and treated. Gonorrhea is a

reportable disease.

Clinical Pearls

1. Patients with gonorrhea need

to be treated for concurrent infection with Chlamydia. Coinfection

with these organisms is seen in 30% of men with urethritis and 50% of

women with cervicitis.

2. Gonococcal arthritis is the

most common cause of monoarticular arthritis in young, sexually active

patients.

3. Suspect gonococcal

conjunctivitis in patients with copious eye discharge and chemosis.

4. Cultures are the gold

standard for confirming the diagnosis of gonorrhea. Selective media

should be used when specimens are obtained from the cervix, pharynx,

urethra, or rectum. Nonselective medium (blood agar) should be used in

culturing joint fluid, blood, or cerebrospinal fluid.

|

|

Chlamydial Infection

Associated Clinical Features

After an incubation period of 1

to 3 weeks, males with urethritis may present with a thin, often clear

urethral discharge and dysuria (Fig. 9.14). Up to 10% of these men may be

asymptomatic. Women may also develop urethritis, which may only cause

dysuria and be misdiagnosed as a urinary tract infection. Cervicitis in

women (Fig. 9.15) is almost always asymptomatic. Women may develop pelvic

inflammatory disease with upper genital tract infection. Men may develop

epididymitis.

|

|

|

|

|

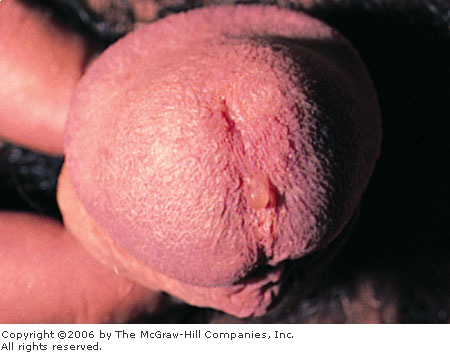

Male

Urethritis Thin urethral

discharge of chlamydial urethritis. (Courtesy of Walter Stamm, MD,

from H. Hunter Handsfield: Atlas of Sexually Transmitted Diseases.

New York: McGraw-Hill; 1992.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cervicitis Mucopurulent cervicitis from chlamydial

infection. (Courtesy of H. Hunter Handsfield: Atlas of Sexually

Transmitted Diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1992.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

For urethritis and cervicitis, Neisseria

gonorrhoeae, Mycoplasma, and Ureaplasma should be considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

The preferred treatment consists

of azithromycin, 1 g PO once, or doxycycline 100 mg PO bid for 7 days.

Alternatives include ofloxacin, 500 mg PO bid for 7 days. Pregnant women

should receive erythromycin base, 500 mg, or erythromycin ethylsuccinate

800 mg PO qid for 7 days. Partners should be examined and treated

appropriately.

Clinical Pearls

1. Chlamydial infection often

accompanies gonococcal infection, and patients being treated for

gonorrhea should also be treated for chlamydial infection.

2. Women with chlamydial

infections may be completely asymptomatic for long periods of time.

3. Consider syphilis serologic

testing and HIV testing in patients presenting with sexually transmitted

diseases.

|

|

Lymphogranuloma Venereum

Associated Clinical Features

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is

caused by a serotype of Chlamydia trachomatis and is primarily a

disease of lymphatic tissue. Initially, LGV is often a painless genital

ulceration that is not noticed by the patient more than 90% of the time.

Patients often present with painful, nonfluctuant inguinal adenopathy,

which is often but not always unilateral (Fig. 9.16). Lymph-adenopathy

may lie above and below the inguinal ligament, causing the "groove

sign" suggestive of this diagnosis. The lesion of lymphadenopathy

may spontaneously open into draining sinus tracts to the skin.

|

|

|

|

|

Lymphogranuloma

Venereum Unilateral left

lymphadenopathy in a patient with lymphogranuloma venereum. (Courtesy

of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Chancroid, granuloma inguinale,

lymphoma, pyogenic or mycobacterial infection, syphilis, and cat-scratch

disease may have a similar appearance.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Doxycycline, 100 mg PO bid for 3

weeks. Rarely, patients may need needle aspiration of the lymph nodes if

they become fluctuant. Serologic testing is needed to confirm the

diagnosis.

Clinical Pearls

1. Patients rarely note the

evanescent ulcer associated with LGV.

2. The lymphadenopathy of LGV

progresses over several weeks.

3. Treatment for LGV requires 3

weeks of therapy for a cure.

|

|

Genital Herpes

Associated Clinical Features

Herpes genitalis presents in

several ways: symptomatic primary infection, first-episode nonprimary

infection, and recurrent infection. Symptomatic primary infection occurs

when the patient develops symptoms upon first acquiring the virus. Some

patients may be asymptomatic when primarily infected with the virus,

however, and present at a later time with their first symptomatic episode

of nonprimary genital herpes. Patients with either symptomatic primary

infection or first-episode nonprimary infection may develop recurrences.

Symptomatic primary genital

herpes is characterized by multiple vesicles that quickly ulcerate into

shallow, painful ulcers (Figs. 9.17, 9.18). The ulcers may coalesce. The

lesions are accompanied by a viral syndrome with low-grade fever and

myalgias. Up to 10% of patients may develop aseptic meningitis. Women may

develop sacral autonomic dysfunction and require urinary catheterization

because of urinary retention. The lesions last up to 3 weeks and heal

without scarring.

|

|

|

|

|

Primary

Lesions—Female Multiple

coalescing superficial ulcerations of primary genital herpes.

(Courtesy of Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Primary

Lesions—Male Multiple

genital vesicles of primary genital herpes. (Courtesy of H. Hunter

Handsfield: Atlas of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York:

McGraw-Hill; 1992.)

|

|

First-episode nonprimary genital herpes and recurrent

genital herpes are less dramatic (Fig. 9.19). Patients with first-episode

nonprimary genital herpes do not have systemic symptoms, have solitary to

several painful lesions, and resolve their symptoms in 1 to 2 weeks.

Recurrences of genital herpes are often heralded by a warning prodrome of

tingling or numbness in the perineal area. Vesicles and their subsequent

ulcers are often solitary. The duration of symptoms is often several days

and usually less than a week.

|

|

|

|

|

Recurrent

Lesions—Female Solitary,

minimally painful lesion of recurrent genital herpes. (Courtesy of H.

Hunter Handsfield: Atlas of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New

York: McGraw-Hill; 1992.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Pustular psoriasis, chancroid,

erythema multiforme, fixed drug eruption, Behçet's disease,

Stevens-Johnson syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum, syphilis, and pyodermic

infection may have a similar appearance.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Primary genital herpes: Acyclovir,

200 mg PO five times daily for 7 to 10 days or until symptoms resolve;

400 mg PO tid may be substituted for patient convenience.

Recurrent genital herpes: Acyclovir,

200 mg PO five times daily; 400 mg PO tid for 5 to 7 days; or

Famciclovir, 125 mg PO bid for 5 days.

Clinical Pearls

1. Women with genital herpes

must be counseled to inform their obstetrician of this history of herpes

when they become pregnant.

2. Genital herpes is the most

common cause of ulcerating genital lesions.

3. Patients may initially

present with full-blown primary genital herpes symptoms or may have their

first clinical presentation as a recurrence of an asymptomatically

acquired infection (Fig. 9.20).

|

|

|

|

|

Herpes

Simplex Virus—Cervix

Erosive ulcerations of the cervix in a patient with genital herpes

infection. This patient may be completely asymptomatic and may

transmit the disease. (Courtesy of A. Wisdom: Sexually Transmitted

Diseases. London: Mosby-Wolfe; 1992.)

|

|

|

|

Chancroid

Associated Clinical Features

Chancroid is caused by Haemophilus

ducreyi. After an incubation period of 2 to 10 days, this disease

presents with multiple, painful, nonindurated genital ulcerations that

are often deep and undermined and may have a purulent base (Fig. 9.21).

Inguinal adenopathy may develop and becomes fluctuant, large, and painful

(Fig. 9.22). Infected lymph nodes may rupture spontaneously. Systemic

symptoms are uncommon.

|

|

|

|

|

Chancroid

Lesions Multiple painful, deep

ulcerations of chancroid. (Courtesy of H. Hunter Handsfield: Atlas

of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1992.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chancroid

Lesions and Inguinal Nodes

Chancroid lesions with an enlarged lymph node. On examination, this

node is tender and fluctuant. (Courtesy of H. Hunter Handsfield: Atlas

of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1992.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Lymphogranuloma venereum,

granuloma inguinale, herpes simplex virus, and syphilis should be

considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Ceftriaxone, 250 mg IM once, or

azithromycin, 1 g PO once. Alternatives include amoxicillin and

clavulanic acid, 500 mg and 125 mg PO tid for 7 days or ciprofloxacin,

500 mg PO bid for 3 days. Large, fluctuant nodes should be aspirated to

prevent rupture; incision and drainage should be avoided to prevent

development of chronic draining sinus tracts. Partners should be notified

of exposure to the disease.

Clinical Pearls

1. Chancroid is usually found

in high-risk populations: drug-abusing, inner-city.

2. Chancroid is a diagnosis of

exclusion, as culturing H. ducreyi requires a special medium not

readily available. Genital herpes and syphilis must be ruled out.

3. The lymphadenopathy of

chancroid is often very tender and fluctuant.

4. Chancroid lesions are very

tender and usually multiple.

|

|

Pediculosis

Associated Clinical Features

Pediculosis can be caused by

either the body louse or the crab louse. Body lice (Fig. 17.21) are not

sexually transmitted and tend to cluster around the waist, shoulders,

axillae, neck, and head. They are extremely itchy; patients may present

with excoriations and intense pruritus. The lice are very small and may

not be easily seen. The larval form of the louse, the nit, may be

mistaken for dandruff in the hair. Unlike dandruff, however, the nits are

extremely adherent to the hair shaft and cannot be brushed out of the

hair. The adult lice and their eggs are often found in the seams of

clothing.

Pubic infestation is caused by Phthirus

pubis, the crab louse (Figs. 9.23, 21.20). Patients may present with

intense itching in the pubic area; however, as many as half of patients

with this infestation may be asymptomatic. Patients may notice the lice

or may note tiny rust-colored spots on their underwear, which represent

bleeding from the sites of louse bites. Nits may be found at the base of

pubic hairs and hatch in 5 to 10 days.

|

|

|

|

|

Pediculosis

Pubis—on Hairs Phthirus

pubis, or the crab louse, in the pubic hair of a patient

complaining of itching. Note also the nits attached to the hairs.

(Courtesy of Morse, Moreland, Thompson: Atlas of Sexually

Transmitted Diseases. London: Mosby-Wolfe; 1990.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Tinea, contact dermatitis,

scabies, and heat rash may have a similar appearance.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Lindane shampoo (Kevell) should

be lathered into the pubic, perineal, and perianal hair, or lindane

lotion applied in the affected areas and left on for 10 min and rinsed

off. Synergized pyrethrins (RID), or synthetic pyrethrins (NIX, Elmite),

may also be used. Since lindane may be toxic, pyrethrins are preferred in

pregnant women and children. Treatment should be repeated in 1 week to

treat any nits that may have hatched. Clothing worn or linen used in the

preceding 24 h should be washed. Mechanical removal of nits attached to

hairs should be attempted. Petroleum jelly or any bland ophthalmic

ointment can be applied to the eyelashes twice daily for a week to treat

infestation of the eyelashes (Fig. 9.24). Sexual contacts should be

examined.

|

|

|

|

|

Pediculosis

Pubis—on Eyelashes Phthirus

pubis lice noted in the eyelashes. (Courtesy of Spalton,

Hitchings, Hunter: Atlas of Clinical Ophthalmology, 2d ed.

London: Mosby–Year Book Europe; 1994.)

|

|

Clinical Pearls

1. Nits are easier to find on

examination than are mature lice; the average number of lice in an

infestation is only 10.

2. Patients with pediculosis

pubis should be considered at risk for other sexually transmitted

diseases and examined.

3. Lindane shampoo or lotion

should not be used in infants under 1 year of age or in pregnant women.

|

|

Condyloma Acuminata (Genital Warts)

Associated Clinical Features

Caused by human papillomavirus

(HPV), these flesh-colored lesions may be flat, sessile, or pedunculated

(Figs. 9.25, 9.26). They often have a cauliflowerlike appearance and are

usually asymptomatic but may be seen or felt by patients or their sexual

partners. They range in size from 1 to 4 mm to masses that may be several

centimeters large (giant warts, Figs. 9.27, 9.28).

|

|

|

|

|

Genital

Warts—Female Verrucous

lesions of the posterior fourchette in a patient with condyloma

acuminata. (Used with permission from H. Hunter Handsfield: Atlas

of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1992.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Genital

Warts—Male Typical

appearance of condyloma acuminata of the glans penis. (Courtesy of

Morse, Moreland, Thompson: Atlas of Sexually Transmitted Diseases.

London: Mosby-Wolfe; 1990.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Giant

Warts—Female Giant warts

of a female patient with extensive condyloma acuminata. (Courtesy of

Morse, Moreland, Thompson: Atlas of Sexually Transmitted Diseases.

London: Mosby-Wolfe; 1990.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Giant

Warts—Male Giant warts

in a male patient with extensive condyloma acuminata. (Courtesy of A.

Wisdom: Sexually Transmitted Diseases. London: Mosby-Wolfe;

1992.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Condyloma lata due to secondary

syphilis is the primary alternative diagnosis (Fig. 9.7). Bowen's

disease, molluscum contagiosum, and carcinoma may have a similar

appearance.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Local caustic agents (e.g.,

podophyllin) are used to treat the lesions; multiple treatment is often

needed, and recurrence is common. Other therapies include cryotherapy,

electrocautery, and trichloracetic acid. Laser therapy or surgery may be

needed in cases of giant warts.

Clinical Pearls

1. Evidence suggests that HPV

is linked with increased risk of cervical cancer.

2. Women with genital warts

need to have a Pap smear to rule out coexisting carcinoma in situ.

3. Large lesions should be

biopsied to rule out cancer.

4. Patients should be advised

that it may take several to many visits to completely eradicate the

condyloma.

5. In cases where the diagnosis

is not obvious, rule out condyloma lata (secondary syphilis) by sending

serologic studies.

|

|

Anal Fissure

Associated Clinical Features

An anal fissure is a longitudinal

tear in the skin of the anal canal and usually extends from the dentate

line to the anal verge. Fissures are thought to be caused by the passage

of hard or large stools with constipation, but they may also be seen with

diarrhea. The fissures are typically a few millimeters wide and occur in

the posterior midline (Fig. 9.29), but they can occur elsewhere. An anal

fissure that is off the midline may have a secondary cause, such as

inflammatory bowel disease or sexually transmitted infection. Although

often seen in infants, this condition is found mostly in young and

middle-aged adults. Patients present with the complaint of intense sharp,

burning pain during and after bowel movements. They may also note bright

red blood at the time or shortly after the passage of stool. Gentle

examination with separation of the buttocks usually provides good

visualization (Fig. 9.29). Anoscopy should be performed, if possible.

|

|

|

|

|

Anal

Fissure A typical anal fissure

located in the posterior midline. (Courtesy of Paul J. Kovalcik, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of inflammatory

bowel disease, ulcerative colitis, or Crohn's disease should be

considered, particularly if the fissure is atypical. Anal fissures may be

the result of a sexually transmitted disease such as Chlamydia, gonorrhea,

herpes, and syphilis. Tuberculosis, anal neoplasms, and sickle cell

disease can also present as an anal fissure. An anal abscess and

thrombosed hemorrhoids may cause similar symptoms but can usually be

ruled out on physical examination.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Acute treatment of anal fissures

consists of anal hygiene, bulk fiber diet supplements to soften stools,

warm sitz baths, and topical anesthetics. Oral pain medication and muscle

relaxants such as diazepam may be required in certain patients.

Clinical Pearls

1. Pain and involuntary

sphincter spasm may preclude a routine digital or anoscopic examination

and require an examination under anesthesia.

2. A proctoscopic examination

should be done at some point to rule out secondary causes.

3. Most anal fissures heal

spontaneously, but refractory cases may require surgical repair.

|

|

Perianal-Perirectal Abscesses

Associated Clinical Features

The perianal abscess is the most

common anorectal abscess. It is associated with pain in the anal area

that is exacerbated by bowel movements, straining, coughing, or

palpation. On examination, a fluctuant and possibly erythematous mass is

found at the perianal region (Fig. 9.30). Perianal abscesses are usually

fairly superficial and easy to drain with local anesthesia. The patient

may notice swelling or a pressure sensation. Perirectal abscesses tend to

be more complex and are named according to the involved space:

ischiorectal, intersphincteric, or supralevator (Fig. 9.31). These are

fluctuant masses that are usually palpable along the rectal wall.

Patients may complain of pain, fever, and mucous or bloody discharge with

bowel movement.

|

|

|

|

|

Perianal

Abscess Swelling and erythema

around the anus consistent with a perianal abscess. (Courtesy of the

American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perianal-Perirectal

Abscesses The anatomy of

perianal and perirectal abscesses is illustrated. Also shown are anal

fissure and internal and external hemorrhoids.

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Crohn's disease should be

considered, because 36% of Crohn's patients have a perianal abscess at

the presentation of their disease. An underlying process may exist, such

as diabetes mellitus, leukemia, or other malignancy.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Incision and drainage of perianal

abscesses should be performed with a small radial or cruciate incision

lateral to the external sphincter. For an uncomplicated abscess, this can

be accomplished under local anesthesia. The cavity should be cleared of

loculations and then loosely packed with iodoform gauze, which should be

removed in 24 to 48 h. All patients require outpatient follow-up.

Antibiotic therapy is not indicated unless there is underlying disease

affecting the patient's immunologic function or the patient appears

septic. Surgical consultation should be obtained for treatment of

perirectal abscesses under anesthesia.

Clinical Pearls

1. Surgical consultation and

treatment may be required in the patient with a large or complicated

perianal abscess or where adequate analgesia cannot be obtained.

2. Consider admission for

debilitated, elderly, febrile, obese, or otherwise ill-appearing

patients.

3. All patients warrant

follow-up referral due to the high incidence of fistulae with anorectal

abscesses.

|

|

Internal-External Hemorrhoids

Associated Clinical Features

External hemorrhoids result from

the dilatation of the venules of the inferior hemorrhoidal plexus below

the dentate line. They have a covering of skin, or anoderm, versus

internal hemorrhoids, which have a mucosal covering. Hemorrhoids commonly

present with an episode of rectal bleeding of bright red blood after

defecation. This results from the passage of the fecal mass over the thin-walled

venules, causing abrasions and bleeding. Symptoms from external

hemorrhoids include complaints of swelling and burning rectal pain.

Numerous associated factors exist, such as constipation, family history,

pregnancy, portal hypertension, or increased intraabdominal pressure.

Hemorrhoids are commonly found at three anatomic locations: right

anterior, right posterior, and left lateral positions (Fig. 9.32). A

thrombosed external hemorrhoid contains intravascular clots and causes

exquisite pain the first 48 h.

|

|

|

|

|

External

Hemorrhoids Multiple engorged

external hemorrhoids are seen in all quadrants. (Courtesy of the

American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.)

|

|

Internal hemorrhoids (Figs. 9.31, 9.33) present with

painless rectal bleeding or possibly the sensation of prolapse. They are

graded according to the degree of prolapse, where the first degree is

identifiable at the dentate line and the fourth degree shows irreducible

prolapse through the anus. Internal hemorrhoids are not typically

painful, whereas external hemorrhoids do cause pain.

|

|

|

|

|

Internal

Hemorrhoids Internal

hemorrhoids are seen in this endoscopic view of the rectum. (Courtesy

of Virender K. Sharman, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Other diagnoses to consider

include infection, perianal or perirectal abscess, inflammatory bowel

disease, malignancy, local trauma, herpes or other sexually transmitted

infection, rectal polyp, or rectal prolapse.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

In the case of severe bleeding,

fluid resuscitation would need to be instituted and the bleeding vessel

located, clamped, and ligated. The treatment for less severe cases

warrants more conservative therapy, including increased dietary fiber,

increased fluid intake, hot sitz baths, bed rest, and nonnarcotic pain

medication. Advanced cases may require surgical consultation and

treatment. ED treatment of thrombosed external hemorrhoids includes an

elliptical excision and extrusion of the clot under local anesthesia.

Clinical Pearls

1. Many patients with any

anorectal problem complain of hemorrhoids. Therefore, careful examination

and consideration of the differential diagnosis should be undertaken with

each patient.

2. Having the patient strain

during the examination may reveal bleeding or prolapse that might

otherwise go unnoticed.

3. Hemorrhoids are a rare cause

of anorectal pruritus.

|

|

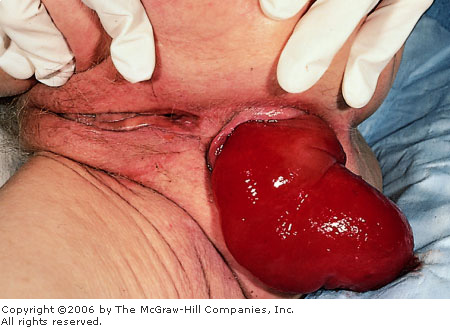

Prolapsed Rectum

Associated Clinical Features

Rectal prolapse occurs when

anorectal tissue slides through the anal orifice; it can include mucosa

or a full-thickness layer. This is due to several anatomic features,

including laxity of the pelvic floor, weak anal sphincters, and lack of

mesorectal fixation. Patients complain of bleeding, mucous discharge,

rectal pressure, or a mass (Fig. 9.34). Problems with fecal incontinence,

constipation, and rectal ulceration are common as well. Prolapse may be

associated with an increased familial incidence, chronic cough,

dysentery, or parasitic infection.

|

|

|

|

|

Prolapsed

Rectum The rectum is

completely prolapsed in this elderly patient. (Courtesy of Alan B.

Storrow, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Other diagnoses to consider

include foreign body, tumor, perianal or perirectal abscess, rectal

polyp, or engorged external hemorrhoids.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Usually reduction is possible

with gentle manual pressure. However, if this cannot be accomplished,

surgical consultation and admission are needed. Surgical treatment is

also indicated with a complete prolapse. All patients should undergo an

anoscopic and sigmoidoscopic examination at some point; if rectal

bleeding is a problem, full colonic evaluation should be completed.

Clinical Pearls

1. This is commonly seen in

children with cystic fibrosis (22%); therefore, all children with rectal

prolapse should have a sweat chloride test.

2. Examination of rectal

prolapse reveals concentric mucosal rings and a sulcus between the anal

canal and the rectum, whereas prolapsed hemorrhoids are separated by

radial grooves and the sulcus is absent.

3. To confirm the diagnosis,

prolapse may be reproduced by having the patient bear down.

|

|

Pilonidal Abscess

Associated Clinical Features

Pilonidal abscesses are typically

seen at or just superior to the gluteal fold (Fig. 9.35) and are more

common in teenage and young adult males. Patients complain of localized

pain, swelling, and drainage but usually do not have systemic symptoms.

The abscess begins with the formation of a small opening in the skin that

develops into a cystic structure involving surrounding hairs. This

opening is occluded by hair or keratin, creating a closed space that does

not allow drainage. The acute abscess contains mixed organisms including Staphylococcus

aureus and Streptococcus, but anaerobes and gram-negative

organisms may also be present.

|

|

|

|

|

Pilonidal

Abscess Redness, fluctuance,

and tenderness in the gluteal cleft seen with a pilonidal abscess.

(Courtesy of Louis La Vopa, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Evidence of cellulitis in the

sacrococcygeal area may result from a simple abscess or furuncle.

However, other causes should be considered, such as anal fistulae,

hidradenitis, inflammatory bowel disease, or tuberculosis.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

An acutely fluctuant abscess

requires incision and drainage under local anesthesia with removal of pus

and debris. The patient should be instructed on meticulous wound care and

sitz baths. Antibiotic therapy is not indicated unless the patient is

immunocompromised. Surgical referral is given, particularly with a

chronic or recurrent cyst, which may require surgical excision and

closure.

Clinical Pearls

1. Pilonidal abscesses almost

always occur in the midline but can have sinus tracts extending off the

midline.

2. Pilonidal disease is three

times more common in men than in women.

|

|

Rectal Foreign Body

Associated Clinical Features

The diagnosis of rectal foreign

body is usually made by history and confirmed by digital examination.

Most often the foreign body is inserted (Fig. 9.36), but it is possible

to have an ingested foreign body trapped in the rectum. The most serious

complication of a rectal foreign body is perforation of the rectum or

distal colon. The patient must be carefully evaluated for evidence of

perforation with x-rays demonstrating free air and clinically for the

presentation of an acute abdomen. Perforation above the peritoneal

reflection is associated with free air in the abdominal cavity and

peritoneal signs. Perforation below the peritoneal reflection presents

with more insidious signs of pain and infection in the perianal or

perineal region. It is important to determine the size, shape, and number

of objects to assess the risk of perforation. In children, rectal foreign

bodies usually present as rectal bleeding.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rectal

Foreign Body Top:

The metallic outline of two batteries is seen in this x-ray. Bottom:

This foreign body (a 7-oz beer bottle) required removal in the

operating room. [Courtesy of David W. Munter, MD (top), and

Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS (bottom).]

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Depending on the clinical

scenario, the diagnoses of sexual assault or child abuse should be

considered.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Removal can often take place in

the ED with sedation of the patient and local anesthesia of the anal

sphincter. If the risk of perforation appears high or adequate relaxation

and anesthesia cannot be obtained, then the patient is prepared for

emergency surgery. After removal, proctoscopic or sigmoidoscopic

examination is recommended to rule out perforation or laceration.

Clinical Pearls

1. A Foley catheter or an

endotracheal tube may be used to release the vacuum effect of some

foreign bodies, and the balloon can be inflated and aid in the removal.

2. A rectal foreign body in a

child should raise the suspicion of abuse.

|

|

Melena

Associated Clinical Features

Gastrointestinal bleeding

commonly presents with the alteration of stool color. By definition,

melena is the passage of dark, pitchlike stools stained with blood

pigments (Fig. 9.37). Generally, but not always, melena results from

bleeding into the upper gastrointestinal tract proximal to the ligament

of Treitz. Black stools have been seen with as little as 60 mL of blood

in the upper gastrointestinal tract, but melena typically does not

develop until 100 to 200 mL is present. Melena can be found in lower

bleeds with decreased transit time, as with an obstruction distal to the

site of bleeding.

|

|

|

|

|

Melena The black, tarry appearance of melena in a

patient with a duodenal ulcer. (Courtesy of Alan B. Storrow, MD.)

|

|

Differential Diagnosis

Melenic stools may occur from

swallowed blood, as from epistaxis or other oropharyngeal bleeding. Dark

or black stools can also be seen with the ingestion of bismuth

salicylate, food coloring, and iron supplements.

Emergency Department Treatment

and Disposition

Patients with melenic stools

should be evaluated in a monitored setting and undergo assessment for

signs and symptoms of hypovolemia and treated accordingly. At least one

large-bore intravenous line should be placed and saline infused.

Depending on the patient's stability, type-specific packed red blood cells

or other blood products may be required. Abdominal radiographs are done

to look for free air in the peritoneum, and gastric aspiration should be

done to assess for active gastric bleeding. Stable patients who present

with melena may be admitted to the ward. Evidence of unstable vital

signs, continued bleeding, severe anemia, or comorbid disease warrants

admission to the intensive care unit. Consultation with a

gastroenterologist should be sought unless patients require more than two

units of blood for resuscitation, which would call for surgical

intervention.

Clinical Pearls

1. Melena is the most common

presenting symptom of bleeding from peptic ulcer disease.

2. Melena represents

approximately 200 mL of blood loss in the gastrointestinal tract.

|

|